Two Roads Diverged in Greenwood

If you’re heading north from Greenwood, Mississippi, you have basically two options. One: Mississippi Highway 7, which goes in a kind of northeasterly direction towards Avalon and Leflore. The second option is US 49 East, which heads north and slightly west out of Greenwood towards Shell Mound, Sunnyside, Minter City, Glendora, and then up towards Webb and Sumner.

US 49 was one of the major evacuation routes for African Americans fleeing oppression and terrorism during the Great Migration. Here in Leflore County, the flow still runs outward: the population has decreased by at least 10 percent in the last decade. And over 40 percent of those who remain live in poverty.

The Evacuation of Leflore County

The evacuation of Leflore has a long history. In fact, the county of Leflore and its seat were named for a man called Greenwood Leflore, who was part white, part Choctaw, and led an evacuation of sorts. An unwilling one, of course. But he became the reluctant leader of negotiations between the federal government and the Choctaw Nation over the latter’s removal from Mississippi.

He warned the Choctaw Nation in the 1820s that “Bad white men will soon come among us, settle on our vacant land, and cheat us out of our property.” I’m not sure even Greenwood Leflore knew how right he would turn out to be.

But there’s a third route out of Greenwood. It’s a slower route, a little bit windier. It kisses the banks of the Little Tallahatchie River here and there. And it’s not a road that you would take if you were in a hurry to get anywhere. But if you’re looking to understand the Mississippi Delta, and by extension, America, this is probably the most important route you can take. Going north on Fulton Street in downtown Greenwood, on the south side of the Yalobusha River, you cross a bridge over the river and the road becomes Grand Boulevard. A little bit further out of town, it becomes Leflore County Road 518.

Losing It All on the Money Road

Better known as Money Road. It’s a road that could not be more ironically named because it passes through one of the poorest parts of Mississippi. And when you say the poorest parts of Mississippi, you mean the poorest parts of America, because Mississippi routinely ranks at the bottom of virtually every metric of financial prosperity in the United States.

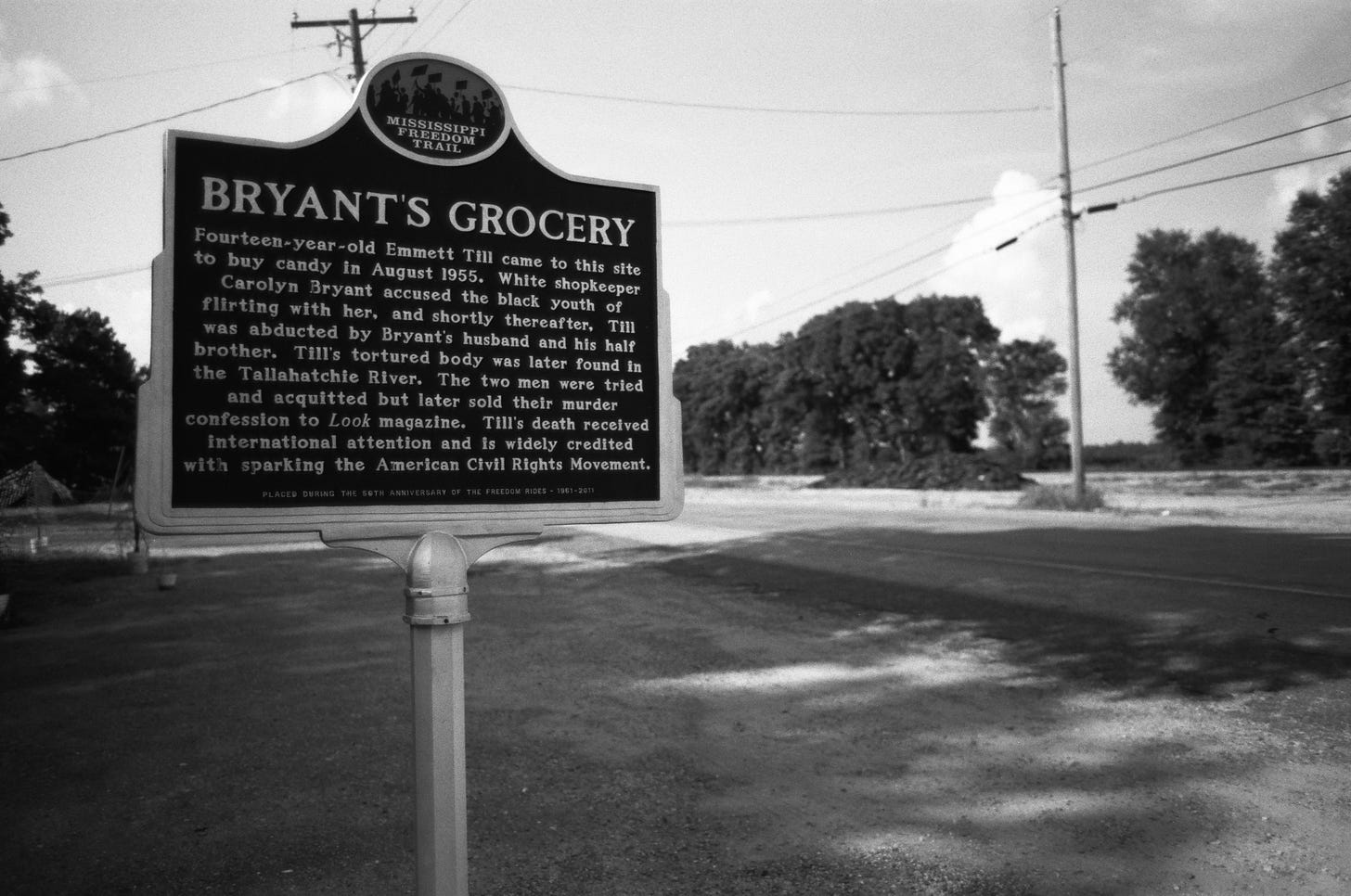

The little village of Money is at the intersection of Sunnyside Road and Money Road, just on the eastern side of the Little Tallahatchie River. There is almost nothing to Money today, but it’s known for one thing and one thing only. In 1955, Bryant’s Grocery and Meat Market was the center of commercial life in, for lack of a better word, downtown Money, which is an extremely generous use of the word “downtown.” Run by Roy Bryant, the grocery catered mostly to African American sharecroppers and farmers who lived in Leflore County and came to Bryant’s Grocery for basic needs.

Choosing What to Remember and What to Forget in Money

On August 24th, 1955, Emmett Till, along with his cousins, Simeon Wright and Wheeler Parker, were at Bryant’s Grocery. Wheeler entered the store and Emmett Till followed after him, and while he was in there, had some form of exchange with Carolyn Bryant, Roy Bryant’s wife. According to both Wheeler Parker and Simeon Wright, when Carolyn Bryant came out of the store, Emmett Till whistled at her. And after that, Emmett was basically a wanted man.

And depending on which version of the story you read, it tends to start here in Money, at Bryant’s Grocery. I’ll talk about money and the Emmett Till story a good bit in my book, A Deeper South, so I won’t go into too much detail about my experience visiting this place over the years, but I’ll just highlight one simple observation you can make yourself if you drive through Money today.

Just north of the intersection of Sunnyside Road and Money Road, facing the Little Tallahatchie River with the railroad tracks behind you, you’ll see a 1950s-era gas station that looks like it’s been immaculately restored. It’s got the pump out there, the white paint, looks like it was put on yesterday. It looks like it could be from the set of American Graffiti. Immediately next door—I mean, it is so close that if you stood between the two buildings and reached out your arms, you could almost touch each one—surrounded by barbed wire and plastic orange fencing, the crumbling ruins of Bryant’s Grocery.

It is covered in ivy. The only visible sign is telling you to get the hell off the property, on what’s left of the front door. Now, it hasn’t been Bryant’s Grocery for many, many years. It’s been other things since then, but this is what it’s known for. And this is what the building represents. And because it represents that, it’s falling to pieces.

Because the family who owns it doesn’t want to restore it. They would rather it fall into the ground and disappear. But that’s not all. They would rather you remember this place like the gas station next door, with all of the visual accoutrements in your imagination of car hops and dudes like James Dean in white t-shirts and blue jeans and black loafers and buxom American muscle cars.

I’m confident that the “they” in question would rather you remember one version of Money, Mississippi than the other, because the same family owns both buildings, the Ben Roy gas station and Bryant’s Grocery, and has chosen to dedicate their resources to restoring one and not the other. It’s a classic parable of the way American memory works.

We would rather you remember one thing, and so we’ll polish that up and put a lot of money into it. The other thing that doesn’t make us look so good, and which reflects a little bit too uncomfortably on ourselves, well, we’re just gonna let that one go back into the ground. And bury it deep down in the earth, where all uncomfortable memories go.

The story of this building and the people who own it is even weirder than that. But I’ll leave that to the book, which I hope you’ll read down the road. Not while you’re driving, but somewhere where you have a chance to pull over for a few minutes, like a Stuckey’s or a place with a comfortable bed with nice sheets and good lighting. (God forbid, not a Buc-ee’s; I would not wish that place on anyone.) But anyway, there’s another reason I don’t really want to talk about Money or Emmett Till right now. And that is because I don’t want you to think that the Emmett Till story is an exception to an otherwise placid and peaceful culture in 1950s Mississippi. And I certainly don’t want to bash Leflore County, because in many ways it’s a really extraordinary, beautiful, mysterious place. But what happened to Emmett Till wasn’t entirely out of character for the Mississippi Delta in 1955.

In fact, Leflore County is possibly the most violent county in Mississippi. More Black people were lynched in Leflore County than in any other county in Mississippi between 1877 and 1950, and that doesn’t include Emmett Till. The Equal Justice Initiative in Montgomery has documented 48 such cases, but the actual number is probably a lot higher than that. I also don’t want to single out Leflore County, because as we’ve been learning about the Mississippi Delta, this place is not an exception to American self-understanding. More often than not, the Mississippi Delta reveals what America is, not what it is not. It is, however, impossible to escape the legacy of Emmett Till around here.

Why We Need to Remember Emmett Till

And that’s good, because in the interest of our national health—psychological, spiritual, historical, mental, and so forth—it is imperative that we remember the Emmett Till story.

And by the way, the fact that three sites in Illinois and Mississippi associated with the Emmett Till story are now officially a part of the National Park Service means that this story will be officially part of the American narrative of itself. Henceforth, that you won’t be able to vandalize with impunity a sign marking where Emmett Till’s body was discovered, for example. That is now a federal felony.

The landscape of Leflore County, yes, it is marked by Emmett Till. And it’s not the only county that is part of that story. I really learned this from Dave Tell’s book, Remembering Emmett Till. We tend to associate Emmett Till with Tallahatchie County, with the farce of a trial in which J. W. Milam and Roy Bryant were acquitted for his lynching in September of 1955. But in fact, the Emmett Till story touches Leflore County, Tallahatchie County, and Sunflower County. And as Dave shows in this remarkable book, there are reasons why certain powers in this part of Mississippi have wanted to keep the story just in Tallahatchie County.

But long before Emmett Till’s rail journey from Chicago to Money, there was a legacy of violence here in Leflore County that isn’t on any historical markers, at least that I’m aware of.

The Forgotten Leflore County Massacre

Decades before Emmett Till, in the 1880s, a man called Oliver Cromwell (not that Oliver Cromwell) came to Leflore County to establish local branches of the Colored Farmers’ Alliance, which was a national fraternal organization designed to advocate and protect the needs of Black farmers, whose interests were not adequately represented by the larger white Farmers’ Alliance.

Now, the two organizations attempted to work in tandem for “purposes of mutual protection, cooperation, and assistance,” to form a sort of hedge against the overwhelming political power of the planting aristocracy.

Now as a side note, Leflore County was late to be developed. It was only in the 1880s when people started to really flock into the county. By 1900, barely 12 percent of the population was white. And during the 1880s and 90s, it was overwhelmingly populated by Black citizens, most of whom were poor farmers. And Leflore County was at the heart of the Cotton Kingdom. Wealth amassed in the county seat of Greenwood was cultivated and farmed out in Leflore County and in other surrounding counties.

In the late 19th century, this area was a cotton-producing juggernaut. Now, white merchants in Leflore County were incensed at this. So Cromwell encouraged his fellow farmers to shop at a Colored Farmers’ Alliance store in Durant, in neighboring Holmes County. Durant is actually a good ways away; it’s clear on the other side of Greenwood. It’s not really even in the Delta anymore. It’s up the bluffs, beyond Lexington, before you get to Kosciuszko. White merchants in Leflore County were furious at their potential loss of business and “circulated reports that Cromwell was an ex convict who could not be trusted.”

Cromwell gets an anonymous letter in the mail. It’s got crossbones, a skeleton, and all of this. It gives him ten days to quit his job and leave the county. Local members of the Colored Alliance rally around Cromwell in a show of support. They call a meeting in support of Cromwell, write their own letter to the white farmers. Claiming to represent “3,000 Armed Men,” about 75 of them march through Shell Mound in military formation to deliver their forceful response to this white provocation. They say they’re going to stick by Cromwell, and if any efforts were made to disturb Cromwell, they would “kill, burn, and destroy.”

Rumors of the prospect of legions of armed Black men amassing in Minter City spread across the county. Here, at last, was the dreaded race war that whites had been fearing, and maybe even secretly desiring, for decades. It was no secret that whites in Mississippi generally resented the rising political and financial power of Black people, and the opportunity to squash a Black rebellion seemed to seethe from the margins of daily newspaper items.

This kind of stuff was on the front page almost every day. And while Cromwell and his alliance were standing their ground in Leflore County, the Executive Committee of the state’s Democratic Party issued a statement to “the Democracy of Mississippi.” Allow me to read to you a portion of it.

“We must show the world that that race created to govern and which has governed all other races where thrown in contact will, in Mississippi, stand by the common civilization of the Union of Mississippi which that race has constructed and maintained. It will never consent to be ruled by another race, as a race manipulated by renegades. The flag of a Caucasian civilization must fly triumphantly at the South, and in every other section of this proud land and throughout Christendom.”

On the very same page of the Atlanta Constitution on which this passage is quoted, there is a report from Jackson, Mississippi that “Oliver Cromwell is said to be a desperate negro of bad character.” Lines like this are used so often in this period, this amounts to almost plagiarism. It’s practically, in our parlance, a meme.

In such a context, what happened next in Leflore County is as unsurprising as it is violent. The governor sent in the National Guard to “restore order.” And when they arrived, they found a mob of white men, armed and mounted on horseback, who had come from all over the place. Over the next four days, as many as 25 Black men, women, and children were hunted down in the swamps around Leflore County, in their homes, and massacred “like dogs.”

When soldiers from the state militia came back to Jackson after the slaughter, they were predictably tight-lipped. The general tenor of official news in the aftermath was that “order had been restored.” And as a news item, it kind of came and went. Oddly enough, it was the white Farmers’ Alliance’s own newspaper that was frank enough about the real motives behind the bloodletting in Leflore County. It approvingly carried an item from the Lincoln, Nebraska Star, suggesting that “the Caucasian of Mississippi does not deem it necessary for the colored farmers down there to have an alliance. The new alliance was therefore broken up, all the members that could be got at having been shot.”

As it turns out, the threats of an armed uprising from the Colored Farmers’ Alliance was mostly bluster, and you can understand why. In reality, they were poorly armed, if at all. As the historian William Holmes has written, “the most telling evidence of a scarcity of arms among the Blacks is the fact that there was not a single report of a white being wounded or killed.”

He also notes that one of the reasons why the massacre didn’t become even bloodier than it was was because white planters stepped in to stop it. Not, again, out of a sense of solicitude or noble, nonviolent resistance, but because Black labor was scarce in Leflore County and a massacre would threaten their labor force.

So, here was a group of Black farmers who were trying to support one another, who were committed to some measure of independence from white power, who were trying to improve their economic prospects, and did so by banding together and trying to support one another. It’s an early instance of what we would now call Black power, or Black empowerment: an attempt to establish a network of Black economic self-reliance that existed outside of white control. It’s a kind of foretaste of the very thing that Stokely Carmichael will be calling for in this same county in the 1960s, which suggests that maybe Stokely was drawing upon a tradition in Leflore County, a legacy of Black self-empowerment, of resistance to white domination, and the formation of Black alliances.

Of course, to say it didn’t go well would be a massive understatement. It was met with obscene violence. And violence that was only suspended out of fear of a loss of income, out of fear of a loss of labor force. So many of the characteristics of the Leflore County Massacre are patterns that are observable in so many similar instances across history, particularly from this period.

An attempt at Black self-empowerment and economic independence is met with overwhelming resentment, fear, and violence. And the story is buried. We never hear about it again. It is not reported with any seriousness, partly because this kind of stuff is happening all the time. You just can’t report on every massacre that is happening to Black people in the 1880s and 90s. I guess that’s the logic. But beyond the fact that these acts of violence are becoming so common as to be almost banal, is something more sinister.

The Power of Memory and the Danger of Forgetfulness

You might say a regime is taking shape in which forgetfulness about the past is an essential, necessary condition of power. And we must remember that Jim Crow was an intentional phase of our history that replaced and supplanted this attempt after the Civil War to empower Black people.

Jim Crow was not what had always been there. It was a deliberate, systematic response to an attempt to empower Black people with the vote, with political office, with economic mobility. And the reaction during Jim Crow was a sustained campaign of violence and intimidation against Black Americans that in some ways was even more intentional, more directly anti-Black than the Civil War had been.

I guess another way to put this is: you don’t have to go all the way to Emmett Till to find instances of white violence against Black people, obviously, but it is to make the Emmett Till case unexceptional. I think the important thing about stumbling upon the Leflore County Massacre is the way it makes Emmett Till’s case almost, while shocking and scandalous, kind of unsurprising.

We should be shocked and scandalized and feel guilty as hell about what happened to Emmett Till. He was 14 years old. At the same time, we should sober up and realize that this wasn’t an exception to the rule. It wasn’t a completely uncharacteristic act of violence against a Black person. It wasn’t an accident. It wasn’t something that just happened. It was the fruit of years and years of formation and habituation and forgetfulness about what our history is, about what we have done to each other already.

I think one of the surprising things for me about something like the Leflore County Massacre is how many times John and I have encountered this sort of episode across the Southeast: episodes that are unmarked, for which there is no historical marker to indicate something like this ever happened. How ubiquitous these episodes are. We started this journey with a Vicksburg Massacre that has no marker, that I had never really even heard about myself practically until the moment I started telling you about it.

This kind of thing happened everywhere. It happened in my own hometown of Atlanta. We never heard about the 1906 massacre of Black people in downtown Atlanta, when we were in school. If there was a marker to every episode of this nature and you stopped to read each one, it would take you a lifetime just to get across the Southeast. A lifetime.

Remembering Emmett Till is essential to our national well-being. I believe that firmly and strongly as I believe anything, and it’s just the beginning. There is a great deal more we have to do as a nation in the interest of restoring our memory of ourself. James Baldwin once wrote that “no one wishes to be plunged head down into the torrent of what he does not remember and does not wish to remember.”

He also said “what the memory repudiates controls the human being. What one does not remember dictates who one loves or fails to love.” And some of the ongoing history, of course, is not just some bag of facts that exists in the basement of our culture to be recovered and visited when we feel like it. It is like a living organism.

The past can nourish the present. In the same way, the present can always be giving new life to the past. One example of this for me is when I was in the Delta in the late summer of 2023 for the dedication of the National Park Service site of Graball Landing where Till’s body was discovered in 1955.

How I got there, I have no idea. I attribute it to some clerical error, but I was grateful to be there with friends of mine like Patrick Weems, who runs the Emmett Till Interpretive Center in Sumner, and whose work has been dedicated to keeping this memory alive and reminding us why it’s important to keep this story alive.

But one episode in particular was especially powerful instance of the way history is alive and the way preservation of buildings enables an encounter with history and with people that might not be possible otherwise.

A Hall of Injustice Becomes a House of Praise

August 27th was one day before the anniversary of Emmett Till’s murder. We were in the courthouse in Sumner, the Tallahatchie County courthouse where Milam and Bryant were tried and acquitted for Emmett Till’s lynching.

The building has been restored, and now it is on the verge of being converted into a NPS site. The occasion for my visit was a memorial service for Mamie and Emmett Till in the courthouse. It was a Sunday. It was basically a worship service. And the courtroom is on the second floor, and it looks like a basic courtroom.

There’s the judge’s bench up front, the jury box on the left hand side. As I’m taking my seat, waiting for the service to begin, a group of young, Black men and women from a local university start to process into the courtroom, walk down the center aisle up on the platform, and turn to the left toward the jury box.

This is the same jury box where twelve white men acquitted J. W. Milam and Roy Bryant for murdering Emmett Till, a crime to which they later confessed rather gleefully in a magazine interview. This site, which we associate with such miscarriage of justice, a predictable miscarriage of justice not at all surprising for 1955 Mississippi, but nevertheless a site that just bears a weight of guilt. Just getting it so wrong—and knowing we were getting it wrong. Of laughing in the face of justice. That’s what this jury box represented.

But on this day, it was occupied by a choir of young Black students from Mississippi Valley State University in Itta Bena in Leflore County. This site of such egregious injustice had now been taken over by a Black choir singing hymns of mourning, of celebration, of promised resurrection, of hope.

The transformation of a site of iniquity into a site of possibility. As if it had been repossessed, reoriented, given new meaning, new life, and if not quite redeemed, then maybe at least put on the path to redemption. This site can no longer be associated with deliberate amnesia. That’s no longer possible.

And that’s not nothing. For the site of where Emmett Till was denied justice, this place now makes possible an encounter with that history, and even an encounter with the random people who happen to show up in that place.

One thing my encounter with a stranger in this courtroom taught me is that the Emmett Till story isn’t over. The Emmett Till story probably doesn’t even have an ending. In fact, no story ever really does.

P.S. Did you know? You can buy books (like Dave Tell’s), support independent booksellers, and support A Deeper South all at the same time by shopping at the ADS Store hosted by bookshop.org.