After Los Angeles

When my essay, “A Deeper South,” was published in Los Angeles Review of Books at 1:00 EST on Sunday, March 10, I was hanging out with dead people. It was fitting—if entirely by accident, or happenstance, or providence—to be on the sprawling grounds of Westview Cemetery in Atlanta where some of the people I wrote about in that essay are buried.

I first visited the site in 1999, when John and I were on our way out of town on Tour 3, headed west for the Mississippi Delta. I took some black-and-white images of family burial sites. Those frames came back badly over-exposed, as if I had come too soon. Then, I only knew some names. It would take another couple decades for the meaning of this place to come into better focus and clearer light, twenty more years for a time to arrive when I could return here with more than just a nominal knowledge of who those people were with whom I share a name and DNA and a history.

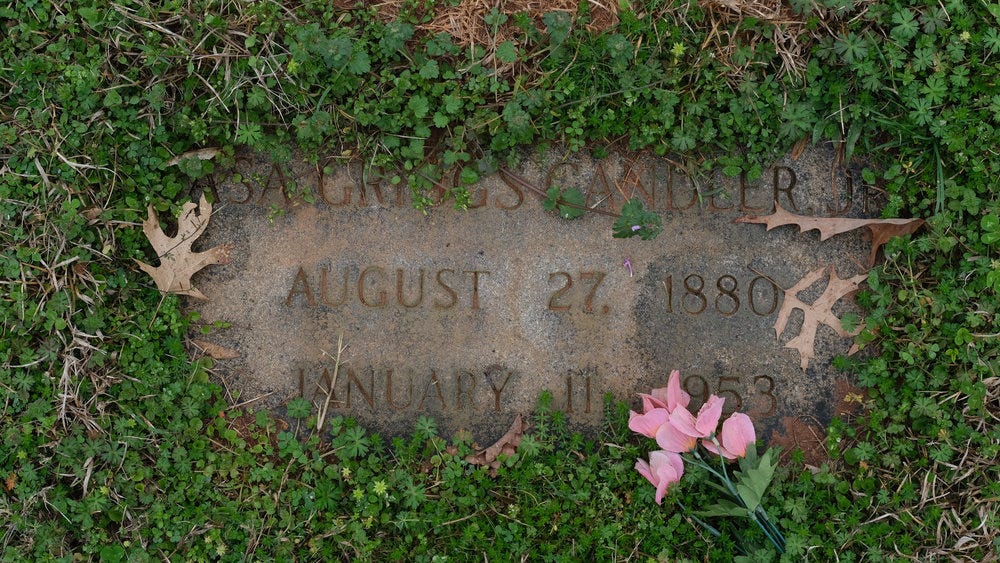

Westview is everything one does not expect of Atlanta: quiet, spacious, calm, medieval. Chartered in 1884, it is the largest civilian burial ground in the Southeast. As owner and president of the cemetery from the 1930s, Asa Griggs Candler, Jr.—the eccentric and high-living son of the founder of Coca-Cola—led the construction of a gigantic and improbably plataresque mausoleum at the heart of the cemetery. It’s hard to place what specific era of historical-cultural nostalgia the elaborate façade is meant to evoke, but it suggests something like the University of Salamanca in northwest Spain. The clinical blue fluorescence of the highly polished marble interior of the mausoleum, by contrast, is all mid-century Presbyterian. Headstones scattered across the 582-acre site—like the once-enfleshed, -ensouled bodies just a few feet beneath the assiduously manicured lawn around them—are similarly bare-boned. There is a just-the-facts, you-can’t-take-it-with-you quality to the information they disclose: names, sometimes dates. Family history has generally come down to me in much the same way: just the names, if that.

The Abbey, on the other hand, is a curiously paradoxical, possibly contradictory, but classically Atlanta-ish flourish: peopled by the dead, the pseudo-ancient abbey sits in the heart of a lush pastoral setting designed to be cost-effective. While Asa Jr. was building the gratuitously lavish medieval-style abbey in the heart of west Atlanta, he was also running afoul of families of the dead by his attempts at “updating” the cemetery. His plan was to do away with traditional up-standing headstones in favor of “level-lot,” memorial-park style markers flush with the ground in order to make mowing the prodigious lawns of the cemetery much less onerous—and less costly. The plan landed Asa Jr. in territory he was very familiar with: legal trouble. In one case, he was sued for $40,300 for “desecrating” the gravesite of one woman’s grandson which she had lovingly tended for a decade. Asa Jr.’s defense, according to the Tampa Tribune, was that “the shrubbery had to be sacrificed to modernization.”

That lawsuit led to a wider movement. In July 1949, hundreds of royally pissed-off, pursed-lipped Southern ladies—fittingly decked out in sundresses and be-flowered hats to protest the de-flowering of their beloveds’ burial sites—turned up at the Georgian Terrace Hotel in Midtown to file a permanent restraining order against Junior to make him stop the deshrubbing. It was such big news that the Atlanta Constitution, in a moment of apparent indecision, ran a rare double headline. “Leveling of West View Graves Banned” read one headline. “Pope Excommunicates Catholic Communists” ran the other. The graves got the bigger headline, but the Red Menace still lurked in the background of the Westview saga. Mrs. Marion Harper led the fight against the cemetery’s leveling program. “We will fight them to the last ditch,” she told the Constitution. “They can’t set the rules and regulations aside. That is Communism and Hitlerism.”

Harper vowed to run Asa Jr. out of town. She didn’t, at least not so dramatically. But he did yield up his stake in Westview not long after the brouhaha, and died in 1953. He was buried in Westview, his grave marked with the just-the-facts, level-lot headstone he preferred. Easily mown over, but no more impervious to the encroachments of time, oblivion, and weeds:

Not far away, my great-grandfather, “The Major,” is buried. In another, older plot not far away, his father, whom I knew for years simply as “The Judge.” Next to him, Asa Jr.’s father. Somewhere nearby, the body of Joel Chandler Harris, whose home, The Wren’s Nest, is a mile-and-a-half east just down the road, next door to West Hunter Street Baptist Church. I stopped there just before visiting the cemetery, to see what I did not see many years before, on the school field trip to Harris’ home: the proximity of two completely divergent narratives about Atlanta’s history, right next door to one another.

Lived geography—or what Michel de Certeau called “practiced space”—can sometimes starkly place right next to one another stories that textbooks prefer to keep separate (and this seems to happen a lot to Joel Chandler Harris). A minute or so on the sidewalk along Ralph David Abernathy Boulevard exposes to view how close we may sometimes come to a confrontation with realities we have somehow managed to keep hidden, or how frequent in our own histories may have been the glancing fly-bys in which we came so close to a genuine mutual recognition of people we didn’t know as well as we thought. For example, after the LARB piece came out, an old high school friend I have known for forty years told me that he grew up attending West Hunter Street Baptist and hearing Abernathy preach every Sunday. His father still serves as a deacon there and serves food to kids at the church’s summer camps. How different from mine his experience of the field trip to Harris’s home must have been, what he saw that I did not see, how it must have felt to him to have that part of his own and our shared city’s history so thoroughly ignored: it is one of those stories I wish I had known a long time ago, and wish I had had the wisdom to ask my friend about when we were in school together.

On the way out of town, one final visit seems called for: Hillcrest Cemetery in Villa Rica where my great-great-great grandfather, the slave-owning Samuel Charles Candler and his wife Martha, a.ka. “Old Hardshell,” are buried. As I wrote for LARB, I know more about them now than I did twenty years ago. They’re not just names anymore. But unlike my first visit to Westview Cemetery in 1999, this time I have arrived not too soon, but almost too late. Amid the fallen pin- and live-oak leaf ground cover that Asa Jr. would not have approved of, there is something I hadn’t noticed in July 2018: the tombstone of Old Hardshell’s son, Samuel Jr—heavily overgrown with lichen, his name and dates virtually blotted out, almost entirely lost to memory. Like so much else.