The Birds of Marietta

Marietta was supposed to have been Atlanta. Established as a white settlement on Cherokee land in the 1830s, the seat of Cobb County was originally intended to be a hub for the Western & Atlantic Railroad. But a political fracas led to the construction of a major terminus twenty miles to the south and to the invention of Atlanta. Hidden away for years in a downtown garage, the zero mile marker that once defined the city of Atlanta is a museum piece now, an orphaned origin-story in marble in a city pathologically un-fascinated with its own origins. Atlanta no longer possesses any single identifiable benchmark for distance, but Marietta does, in the form of a 56-foot high, eye-rolling mechanical steel hen known locally as “The Big Chicken.”

It is what the Zero Mile Post in downtown Atlanta once was: a sign to measure space with, a roadside way-marker by which to orient travelers (and even pilots). Distances were measured from the Zero Mile marker the way directions are now issued with reference to the giant metal bird: “Turn left at the Big Chicken,” “Go three miles pat the Big Chicken,” and so on. In an expression that could almost describe the city today, the WPA writers described Atlanta in 1940 as a “lusty offspring of railroads—restless, assertive, sprawling in all directions and taking in smaller towns in its incessant push toward greater growth.” Marietta is one of those towns. It is our first stop on our seventh tour.

Atlanta is less libidinous about its railroads these days, but since 1940 Marietta has been absorbed into the sprawling Atlanta metroplex and the rapidly metastasizing amnesia that goes along with it. Since white folks began fleeing the city of Atlanta following the Brown v. Board decision in 1954, Atlanta has outsourced to Marietta a good portion of its workforce, its baseball team, a share of its living memory, and one of its most notorious crimes.

Though it now serves a Kentucky Fried Chicken, The Big Chicken was built in 1963 for Johnny Reb’s Chick-Chuck-N-Shake, an indication of the way in which the conflicted language and history of the Confederacy is written onto the landscape here.

Across the ten lanes of Interstate 75, a much less eye-catching historical marker stands in the middle of a concrete walkway next to a Mexican restaurant. It marks the spot where Leo Frank, a Jewish superintendent of the National Pencil Company warehouse in Atlanta, was lynched by a mob of white men in 1915. A small, black granite monument erected by Jewish organizations puts Frank’s killing in the context of the roughly 570 mostly African-American Georgians lynched between 1880 and 1946, and “the thousands across America, denied justice by lynching; victims of hatred, prejudice, and ignorance.”

Frank was tried and convicted of the murder of Mary Phagan, a 13-year-old girl whose body was discovered in the basement of the National Pencil Company on April 27, 1913. She had come to collect $1.20 in pay, and never left the warehouse. Someone had strangled and apparently sexually assaulted her.

The Leo Frank case was one of the most sensational in Atlanta’s history, and became fodder for the city’s three major newspapers—The Atlanta Journal, The Atlanta Constitution, and William Randolph Hearst’s The Georgian—which waged daily battles for readers with increasingly attention-grabbing headlines. Reporters made names for themselves during the coverage, including The Journal’s Harold Ross, who later founded The New Yorker.

Frank, whose death sentence was commuted to life imprisonment in 1915 by outgoing Governor John Slaton, was vilified by populist politician Thomas E. Watson, who used his own rag, Thomas Watson’s Magazine, to press the case against Frank. Watson exploited familiar racist tropes in order to stoke the fires of white outrage: “Leo Frank was a typical young Jewish man of business who loves pleasure, and runs after Gentile girls. Every student of Sociology knows that the black man’s lust after the white woman, is not much fiercer than the lust of the licentious Jew for the Gentile.”

Two months after Slaton’s commutation, spurred on by rhetoric like Watson’s, a mob of white men called The Knights of Mary Phagan kidnapped Frank from his cell at the state prison in Milledgeville, and drove him to Marietta, where they planned to murder him on Mary Phagan’s grave. He was instead hanged in a field next to where the Big Chicken now stands. Postcards of his lynching were sold for 25 cents, and portions of the rope used to hang him sold as souvenirs.

In reading Steve Oney’s outstanding and thorough account of the Frank case, And the Dead Shall Rise, I was struck by how many names I recognized. I had never heard a word about Leo Frank as a kid, but I went to school with people with the same names as some of the central figures in the trial of Leo Frank: Selig, Dorsey, Hopkins, Elsas, Frank.

I am even closer to this history than my education or family lore let on: when Governor John Slaton commuted Frank’s sentence, some responded with threats against his life. To protect him from a potential mob, a detachment of the Georgia National Guard was sent to his home, led by Major Asa Warren Candler, my great-grandfather.

Shadowed by overt anti-semitism in the press and in the popular culture, Frank’s trial was a total mess. The trial judge, Leonard Roan, was not convinced of Frank’s guilt, but sided with the jury’s guilty verdict. Without pronouncing on his guilt or innocence, Governor Joe Frank Harris pardoned Frank in 1986. The case remains both controversial and painful: over a hundred years later, some are still pressing the state for an official exoneration, despite the Phagan family’s insistence upon Frank’s guilt.

From the beginning, though, Mary Phagan’s murder was colored by the mythology of the Lost Cause, and her life was quickly turned into a symbol. In the revisionist narrative of the Lost Cause, the Confederacy stood for the defense not of the institution of slavery but of home, embodied in the virginal feminine purity of the Southern Woman. For example, the Confederate monument in Meridian, Mississippi declares that “It was the teaching of the Southern home which produced the Southern soldier; The deep foundation of whose character was devotion to duty and reliance on God. By the side of every marching Southern soldier there marched unseen a Southern woman.” This retroactively redefined holy war in defense of white women’s virtue was the context for the the fever of lynchings of African-Americans from 1880-1940 and even later. When Emmett Till was lynched in 1955, it was, in the minds of his murderers, due to an unforgivable breach of this unwritten code of Southern conduct.

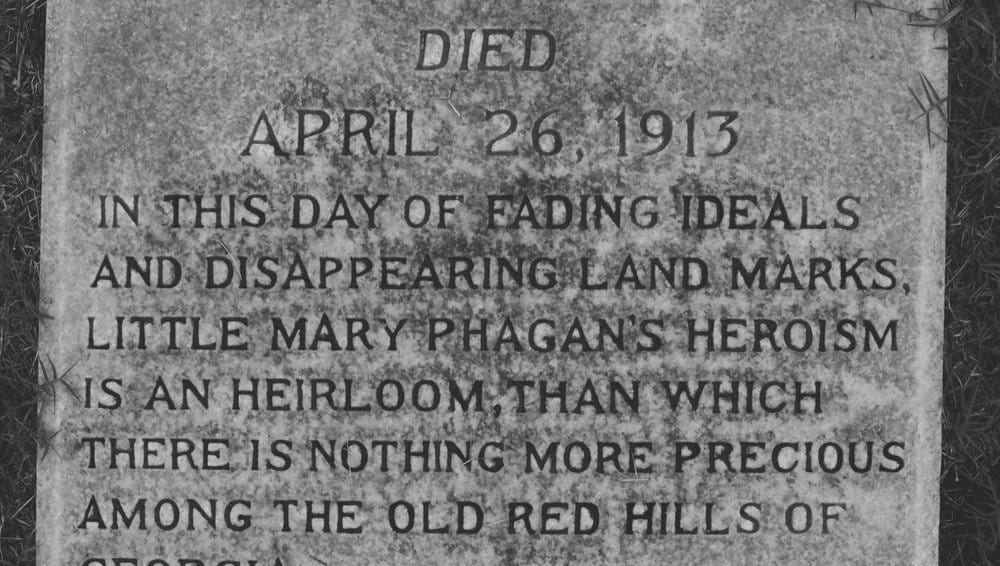

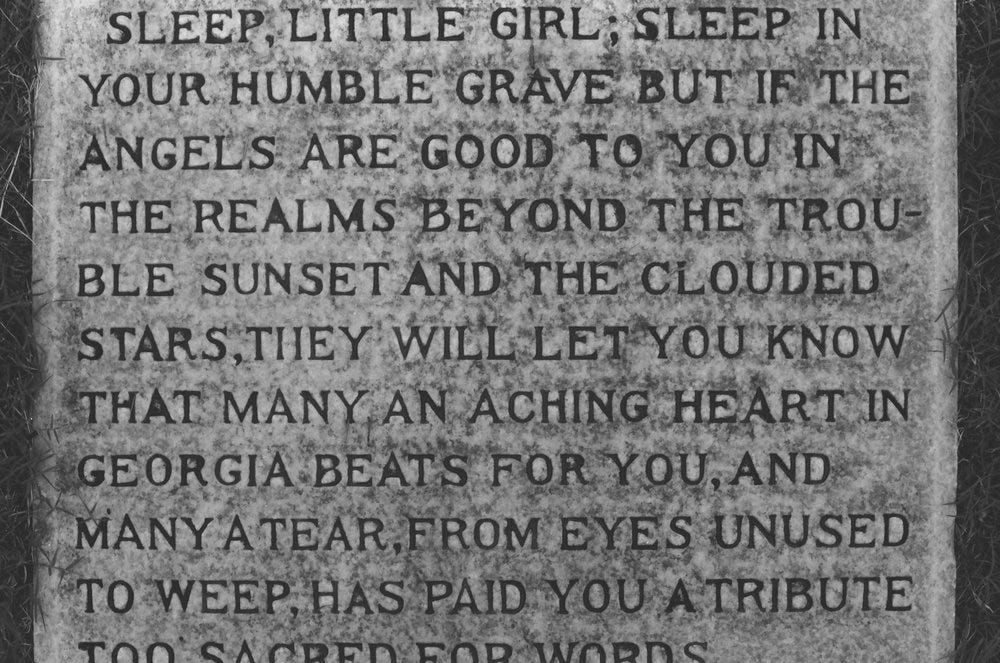

But Mary Phagan quickly became a cause célèbre of neo-Confederate mythology. Her grave in Marietta City Cemetery features a headstone erected by the United Confederate Veterans. Her body lies under a slab whose text remembers Mary for her “heroism,” and treats her tragic death as a commentary on “this day of fading ideals and disappearing landmarks.”

Next to Phagan’s tomb are two more recent markers. One calls her “Celebrated in Song,” a reference to “Little Mary Phagan,” the popular ballad written about her by Fiddlin’ John Carson and Moonshine Kate, frequent musical accessories to Tom Watson’s political rallies. The song is unambiguous about Frank’s guilt, and the motive for his act:

She fell upon her knees, to Leo Frank she pled

Because she was virtuous, he hit her across the head

Another marker, presumably erected by the Phagan family, has even more to say. “No Phagan was involved in the lynching,” it reads. And, for emphasis: “The 1986 pardon does not exonerate Leo Frank for the murder of ‘Little Mary Phagan.”

Next to the marker, a small stone urn holds a pile of stones, and a red, white, and blue enameled tile of the Confederate battle flag.

Mary Phagan’s shocking murder understandably aroused equally intense sorrow and desire for revenge in Georgia and elsewhere; but in this context her death is narrated as a morality tale about the evils of Jews, blacks, and Yankees, and the moral rightness of the Confederate legacy. The most recent marker is simply the latest example of a trend that set in early, whereby Mary Phagan’s death was almost immediately repossessed, managed, put in service to a mythology. The language and mis-en-scene of her memorial here lend her murder the specter of a religious sacrilege—she was killed on a high holy day for the Lost Cause: Confederate Memorial Day, 1913.

The city cemetery is part of a larger burial ground that includes one of the nation’s oldest Confederate cemeteries. Established in 1863, it is still carefully maintained by local citizens. In addition to the monument erected in 1908 by the United Daughters of the Confederacy to the memory of the 3000 soldiers “who died for a sacred cause,” new monuments are still being erected. Thirty-two tons of granite erected in 2009 list the names of all the known Confederate dead here, in a city-owned park at the edge of the cemetery. Nearby, bronze statues of women representing the Ladies’ Memorial Association commemorate their dedication to the “cause.” A new monument to “The Confederate Soldier” was erected in 2014. Some visitors—confusedly or perversely, who knows—have left a row of copper pennies at the soldier’s feet, the face of Abraham Lincoln turned outward.

The cemetery remains an active site for the cultivation of Lost Cause myths. Rebel flags punctuate the lawn and fly overhead. It was here that local Confederate sympathizers—including some members of the KKK—came armed in 2017 to protest the “desecration” of Confederate monuments. The Cemetery’s guest book contains remarks from many visitors, many of which praise the “patriotism” and “principles” of the Confederate war dead. Deo vindice, they regularly read. One entry—by Grace from Indiana—does not toe that line. “God bless the souls who once thought it was right to claim ownership over another human soul. Thank God we as a country are no longer so brutal,” Grace writes. A later, disapproving visitor has crossed out her comment with an X.

The effect of the Confederate Cemetery is numbing. Everywhere you are met with words: explanations, apologias, mini-lectures. This is true of almost every Confederate burial ground, in my experience: they are wordy sites, they take great pains to talk at you, convince you of something, tell you how right they were.

When someone talks at you that much about themselves, you begin to wonder what it is they have to hide.

Not a mile away from the Confederate Cemetery, the Marietta National Cemetery is a jarring contrast. Visiting them back-to-back brings into relief just how different these two modes of remembering the dead are. Marietta’s national cemetery holds the graves of over 10,000 Union soldiers marked by identical white headstones like the ones in every national cemetery. The scale of human grief is vast, overwhelming, staggering. Apart from the names on the headstones, the only words on the entire hilltop site are on a plaque reproducing the text of Lincoln’s Gettysburg Address. The rest is silence.

Memory is a cemetery

I’ve visited once or twice, white

ubiquitous and the set-aside

Everywhere under foot,

Jack robin back on his bowed branch, missus tucked butt-up

Over the eggs,

clouds slow and deep as liners over the earth.

—Charles Wright

Encircling row upon row of white death-stones, like an undulating tide of human loss. For what, we are not told. Bluebirds flit from the arch-topped headstones of the Union dead. A red-headed woodpecker alights on the trunk of a high oak. Their calls pierce the silence. I try to capture one on film, but fail. Each time it flits off to another headstone before I can catch it, marking, perhaps, the distance between the dead and who we want them to be.