Specter of Camilla

The WPA Guide describes Thomasville, Georgia, as one of those quaint Southern towns where winters are "short and mild," a fragrant, rose-garlanded small city where "the streets are lined with Red Radiances," a beneficiary of the disposable income of northern capitalists who "built palatial winter homes, which are maintained in the manner of old southern plantations and provide employment for an average of three hundred people each." In Thomasville, Henry Grady’s new southern chickens came home to roost: in 1940 the county could claim "sawmills, tobacco markets, cotton gins, an iron foundry, a concrete-pipe plant, and a crate and basket factory," and apparently not even the irresistible march of enlightened northern progress could resist the allure of packaged southern nostalgia. Not long after Grady was appealing to deep-pocketed Yankees in Tammany Hall in 1886, Georgia became the world’s largest producer of naval stores: lumber, pine gum, pitch, turpentine, rosin.

Even now the region is rife with longleaf and slash pine, pecan groves that stretch to the horizon. And while the naval stores industry is a shadow of its former self, the area retains its allure for people with money to burn. Cap’m Charlie Croker, former Georgia Tech football hero, filthy-rich Atlanta developer, and the eponymous title character of Tom Wolfe’s A Man in Full, owns a massive tract of south Georgia property that he calls

Turpmtine Plantation! Twenty-nine thousand acres of prime southwest Georgia forest, fields, and swamp! And all of it, every square inch of it, every beast that moved on it, all fifty-nine horses, all twenty-two mules, all forty dogs, all thirty-six buildings that stood upon it, plus a mile-long asphalt landing strip, complete with jet-fuel pumps and a hangar all of it was his, Cap’m Charlie Croker’s, to do with as he chose, which was: to shoot quail.

Almost as an avatar of Thomasville’s wealth, the "Big Oak" is one of the state’s oldest trees. Born in roughly 1680, the canopy of the massive live oak occupies almost an entire city block. It’s the sort of feature that turn-of-the-century industrialists could not find back home in Massachusetts and New Jersey. It’s spectacular, and almost impossible to capture adequately on film. I try a few different angles, and give up. But—as I learned later—if you want your picture taken under the shade of the Big Oak, you can dial a telephone number from your smartphone and a camera atop a light pole across the street will snap a selfie of you and the giant tree.

Here is mine:

The wonder of a travel photo in 2019: you don’t even have to be there for it.

It’s not the only way Thomasville has slid on into the twenty-first century. The historic town center along Broad Street is paved with cobbles, and lined with the kind of shops you see in towns that aren’t dead yet. Thomas Drug Store has been in operation since 1881. The improbably hip Grassroots Coffee Shop opened in 2009, and has been roasting their own beans since. Naturally—following a new rule since the first Dante Moment—we stop for a to-go cup. The chipper barista fills up the bougie YETI travel mug someone gave me because no one ever admits to buying a YETI for themselves. The place is thriving, full of life. It’s not what we expected of Thomasville, nor is the cheese shop across the street. Sweet Grass Cheese Shop opened about the same time as the coffeeshop, and they serve up old-world cheeses made from their own cows at their dairy farm up the road on US 19. I revise whatever half-baked rule of thumb I may or may not have had about urban health, and tentatively conclude that there is no better indicator of a town’s overall spiritual well-being than the presence of a cheese shop. (Not even über-hip Asheville has a cheese shop. You do the math.) What’s more, in Thomasville we find our first opportunity to offload the stash of half-crushed aluminum cans, random cardboard and plastic pieces that have accumulated in the belly of the minivan. Thomasville has its own recycling center. Pretty fly for south Georgia, we both remark, revealing how far south our own Atlanta-bred prejudices can sometimes run.

Thomasville becomes the first real instance of the kind of phenomenon we were hoping to see in 1997, but after the fact: it’s evidence of a recent and welcome revival in small towns, a show of local resistance to the forces of homogenization that course along interstates and off exit ramps everywhere in America. The Big Oak seems to presage a hopeful future for Thomasville.

But as always, darker tales are less self-evident.

En route north to Camilla, we pass through the railroad town of Meigs, one of the poorest municipalities in the country. Barely a thousand souls live here—roughly as many as lived here a hundred years ago—but the town sits in two counties. A silver water tower, adorned with a painted cotton boll, is the only feature on the skyline. Weathered plywood predominates on the storefronts along Depot Street. A fluorescent light burns coolly from the ceiling of Meigs Grocery. There is no cheese shop.

En route to Camilla, where John’s grandfather Herbert grew up, he tells me about his paternal ancestor, Eben Hayes. Eben was from Marion County, South Carolina, and joined the Republican Party in 1868. It was a courageous move for a white man in post-war South Carolina, and brought Hayes a lot of enemies. One of them was the planter-publisher of the Marion Star, who once offered a bounty for Old Eben’s head, and refused to capitalize his name in print. The paper called him "a pretended minister of the gospel." In 1870 The Charleston Daily News—not a pro-Republican newspaper—called him "an old uncleanly white man." Eben was mocked for his advanced age, but in the state house it was a sign of his seniority. He was revered as "the Patriarch of the House."

Eben Hayes’ story is an inspiring tale of conversion, a courageous about-face against the grain of Southern white society. Five years after the War, Reconstruction was not especially popular in the South Carolina Low Country bulwarks of the Lost Cause. A change of heart, or an act of moral conviction that cost Eben Hayes a lot. Eben Hayes, see, was a scalawag.

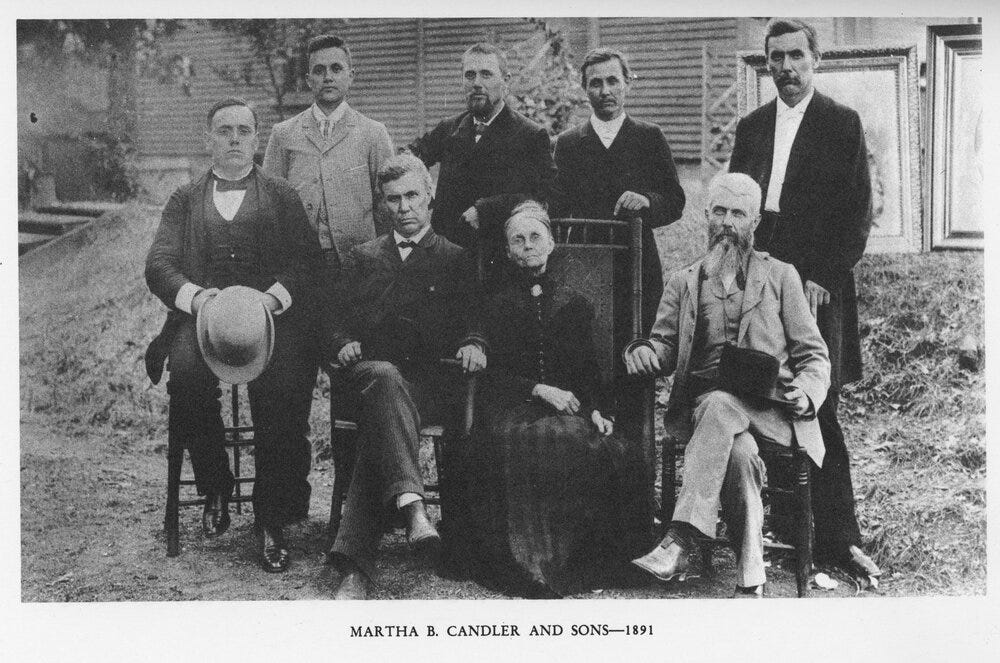

I don’t have any similar stories of costly moral courage in this period of our family history, when a family member stood on a principle so contrary to local convention. There are no scalawags in the family tree, no Damascus Roads in the way Camilla represents for John a story of exemplary nobility, of principled counter-cultural moral fortitude. When my family members of that era were sitting in Congress or in the halls of elected power, they were in the ruling class, not in the dissenting one. They were Democrats, and generally accepted—either explicitly or tacitly—the logic of white supremacy. Milton Anthony Candler was the oldest of eight boys; he was 24 and already serving in the Georgia legislature when his youngest brother, my great-great-grandfather John, “The Judge,” was born in 1861. The three youngest brothers in that family—Asa, the Bishop, and the Judge—were almost of a different generation from Milton. They were principled New South Methodists, teetotaling law-and-order men, whose faith was more in progress through commerce and education than in their eldest brother’s Old South politics of resentment. While they may have come later to slide away from Milton’s sour-faced politics, the younger brothers were nevertheless beneficiaries of the white supremacist establishment which Milton and their cousin, Governor Allen Candler, helped to build. Two differing visions of the Southern future emerged from one set of brothers in the late nineteenth century, but in 1870 my family history was on the opposite side from Eben Hayes, and the line between those two sides is drawn in Camilla.

On September 19, 1868 a "speaking" was to be held in Camilla for the Republican Party. Basically a political rally with a fife-and-drum band, it drew hundreds of newly-enfranchised African-American voters along the road from Albany into Camilla, the seat of Mitchell County. Word spread that whites in Albany were stockpiling weapons, and preparing for war. Some of the blacks who marched into Camilla that morning were carrying rifles and shotguns out of a habit of self-preservation, but few of them came with ammunition. Whites in Mitchell County spread rumors of an armed black insurrection, the looming race war that would come to terrorize paranoiac white consciences for decades. When the African-American delegation, led by representative to the state assembly Philip Joiner, arrived in Camilla, they found a mob of armed white men, at least fifty strong, waiting for them. Embittered and trigger-happy whites began firing on the marchers. Chaos ensued—blacks fled from heavily-armed, horse-mounted whites and sought shelter in the heavily-wooded swamps or "among the gallberry bushes and bamboo briars &c. hanging over from the banks," as James Washington did. When it was over, ten or more African-Americans where dead, thirty more wounded. Those that survived and still believed in the democratic process were intimidated into sitting out the general election later that November.

Joiner had been one of twenty-nine African-American members of the state legislature who had been removed from office at the beginning of September 1868, just a few weeks before the act of terror in Camilla. Whites like those who massacred African-Americans in Camilla had been energized by the removal, and by the idea of whites "retaking their government," an idea first proposed a few weeks earlier in the Georgia Senate by Milton A. Candler.

So Camilla is a dividing line: it marks where the words of one man with whom I share a name and an ancestor led ultimately to the deaths of innocent victims.

1868 marked a kind of conversion for Eben Hayes, but not for Milton Candler. Six years later, Milton was on the Democratic ticket for the 5th United States Congressional District. He had been out of public life for two years, but voters remembered him. In 1874, he was still riding on the strength of his political gestures six years earlier, when he had initiated a motion to have three newly-seated African-American senators removed from the Georgia Senate. The motion failed, but a Democratic voters remembered Milt. “A pale, low-browed, slender individual; he possessed a full, sonorous voice and an unusual energy of expression and delivery,” a contemporary said of him. At a barbecue in 1874, he deployed that energy behind his strengths: exploiting white fears. The Republicans, he said, "are not satisfied with simply degrading the whites, and depriving some of the best and most intelligent of the right to vote, or have any influence in the government, but they propose to grant that power to the ignorant and degraded negro, and to make him competent to vote and hold office. And your dearest interests and rights are to be entrusted to the colored people, who have already demonstrated to the world their incapacity to administer any civilized government—a race without virtue or intelligence, who exercise political power not for their own good. No, my friends, that is not the secret. The reason is that they may perpetuate power in that party that hates you and does not love them—a party that hates the constitution of our fathers."

"The War of Northern Aggression" was not just a quaint, tounge-in-cheek expression for Milton. He attributed the "desolation" of the war explicitly to the Republican Party, who "inaugurated and carried [it] on." "They make war on the whole white race of the south," he fumed, "destroyed everything hitherto held sacred by our wisest and best men." He railed against the proposed Civil Rights Bill because it would force blacks and whites to socialize together. "You will not be allowed to say to a negro when he takes a seat by your wife or daughter that you object," he said.

I have no way of knowing whether or not Milton was a member of the Klan, but he sure as hell pontificated like one. If he wasn’t, he certainly hung out with people who were. According to Milton’s granddaughter, when he was elected to Congress in 1877, "the men of Decatur held a torch-light parade from the town out to the farm, some on foot, some on horseback, their torches flickering up through the trees of the avenue." On Sunday afternoons in the 1870s, former Confederate General and Georgia Governor John B. Gordon would ride his horse over from “Sutherland,” his Tara-esque mansion in Kirkwood, to Milton’s farm in Decatur to talk politics. It is generally accepted that Gordon was the de facto head of the Klan in Georgia, although it operated under a different name. What he and Milt likely talked about on the veranda is—well, you do the math.

Gordon was only the de facto head because the organization of the Klan was “never perfected,” as he testified before Congress in 1870. “I was spoken to as the chief of the State,” Gordon said. While he defended the organization as “a brotherhood of the property-holders, the peaceable, law-abiding citizens of the State, for self-protection” against negroes who “were being incited throughout the South to antagonism and violence,” Gordon denied—improbably—knowledge of any acts of violence committed by disguised vigilantes against African-Americans. In an intense line of questioning, Representative John Coburn, a Republican from Indiana, presented Gordon with a series of examples of “outrages” against African-Americans intended to prevent them from voting in the recent election. Gordon denied any knowledge of any such intimidation, and held firmly to his belief in the “kindly” relationship between blacks and whites generally. But one exchange revealed that Gordon’s memory of racial harmony might not be so trustworthy:

Question. You said something about jurors. Do you say that, as a general rule, whites and blacks serve together on juries in Georgia?

Answer. O, yes, Sir.

Question. Do you know that to be a fact?

Answer. I have seen blacks and whites on juries together.

Question. How often?

Answer. I have never seen any juries often.

Question. Where did you ever see a black man on a jury?

Answer. I think I have seen them on juries in Atlanta.

Question. Are you sure of it?

Answer. No, sir; I am not.

Gordon’s appearance before Congress ended with one final series of questions. James Burnie Beck, a Democrat from Kentucky, asked Gordon about the 1868 ruling in the Georgia legislature that removed negro legislators from the general assembly. It was a leading question: Beck—a vigorous defender of the “late insurrectionary states”—was attempting to get Gordon to attest that Republicans had supported the move as well. “Governor Brown,” Gordon replied, “who is now the chief justice of Georgia, and who is considered one of the best lawyers we ever had, took the position emphatically all over the State that the negroes could not hold office; and I believe that the best lawyers of his party agreed with him.” Gordon’s response echoed almost verbatim the language of Milton Candler in his introduction of a resolution in the Georgia Senate a few years before, which appealed to Governor Brown, “one of the ablest lawyers of the Republican Party of Georgia,” as implicit bipartisan authorization of the racist expulsion.

And then, after hours of interrogation, it was over. The former General was free to go. I do not know if—as John Gordon gathered his papers, smoothed the front of his coat, and walked out of the House chamber—the specter of his friend Milton Candler hung in the air.

But it does now.

References

"The New Regime," Charleston Daily News, 14 March 1870, p. 1.

Isaac Wheeler Avery, The history of the State of Georgia from 1850 to 1881, embracing the three important epochs: the decade before the war of 1861-5; the war; the period of Reconstruction (New York: Brown & Derby, 1881).

Atlanta Constitution, 10 September 1874, p., 3.

Report of the Joint select committee appointed to inquire into the condition of affairs in the late insurrectionary states, so far as regards the execution of laws, and the safety of the lives and property of the citizens of the United States and Testimony taken (Washington, DC: Government Printing Office, 1872).

“Recollections of Milton A. Candler’s daughter, Claude Candler McKinney, by her daughter Caroline Murphey McKinney Clark,” Candler Family papers, Stuart A. Rose Manuscript Library, Emory University.