Due east of Greenville on US 278, about eight and a half miles, is Leland, Mississippi. Leland is blues country. I mean, all the Delta is blues country, but it’s in Leland that we start to get our first taste of the Mississippi Delta as the land of the blues.

I talk about this in my forthcoming book, A Deeper South, so I won’t tell you too much about this story, but my first time here with John, we met a guy playing his guitar on the sidewalk. His name was Pat Thomas. His father was James “Son” Thomas, who’s a legend of Mississippi Blues. He was also a really famous artist: Son Thomas worked as a gravedigger for a while and he would make these skulls out of clay and paint. There’s a blues museum in Leland that showcases some of these skulls, which were also featured in an exhibit in the Corcoran Gallery in Washington, DC. Son Thomas was in the second generation of great blues musicians. He was born in 1926, a couple years before Robert Johnson made those famous recordings that forever set the stage for Delta Blues.

But he’s not the only blues musician who is from Leland. Johnny Winter, a white blues musician, he’s from Leland too.

You expect to run into the birthplaces of blues musicians all over Mississippi, but there’s one person I’m pretty sure you did not expect to meet here in the Delta.

I’m willing to bet that if you polled a random sample of people on any American street, of those people who are old enough to recognize Kermit the Frog, and point him out in a lineup, that ninety-nine out of a hundred of those people would not tell you that Kermit the Frog was born in Leland, Mississippi. Jim Henson, creator of the Muppets, was born in Greenville, but grew up in Leland, which explains the otherwise bizarre and completely unaccountable existence of the birthplace of Kermit the Frog Museum in Leland, Mississippi.

Plenty of frogs in the Delta. Probably plenty of frogs in Deer Creek, on the banks of which sits the birthplace of Kermit the Frog Museum.

In that famous opening scene in The Muppet Movie—the Muppet movie inside the Muppet movie, that is—Kermit is sitting on a log and what looks like a swamp playing the banjo singing “Rainbow Connection.”

It’s a pretty iconic scene from the Muppet canon. That scene was originally supposed to be shot in Georgia, I guess in the Okefenokee or something. But it proved impractical. And this being Hollywood, instead of flying crews and camera equipment out to the Okefenokee swamp or wherever they were intending to do this, they cut down about 40 cypress trees and flew them back to Hollywood, where they were set up in a studio. An artificial swamp was created in some Hollywood backlot, and to achieve the effect of Kermit sitting on a log playing the banjo, the special effects crew for the film built a submersible for Jim Henson to lay down in underneath Kermit. According to an article from American Cinematographer in 1979, the year the film came out, there was one instance when Jim Henson spent “more than three hours underwater trapped inside this container. His only contact with the outside world was his little monitor which gave him a visual account of Kermit’s performance.”

I don’t know if Jim Henson ever encountered singing frogs on Deer Creek in Leland, Mississippi as a boy. But I’ve spent enough time in the Delta to know it’s entirely possible.

If you didn’t think of the Mississippi Delta as a land of surprises, well there you go. We all expect to encounter the blues when we’re in the Delta. No one expects to encounter Jim Henson, unless you happen to be a total Muppets nerd. And if you are, props to you, because they’re awesome.

But stay straight on US 82 for another fifteen miles, and you come into Indianola, Mississippi. Albert King was from Indianola. B. B. King (no relation) grew up in Indianola, too. This place is saturated with the blues. It’s populated by blues royalty. You encounter them everywhere.

The concentration of so many great blues musicians may have something to do with the fact that Greenwood, the county seat of Leflore County, was, according to the WPA Guide, “the heart of what is reputed to be the greatest long staple cotton growing area in the world.”

Long staple cotton, by the way, refers to the length of the actual fibers of cotton that constitute the cotton boll, the fluffy white bloom on the cotton plant that looks like...well, a cotton ball. The longer the staple, the better quality cotton.

When the length of a fiber of cotton is between 1 1/8 and 1 3/8 inches, then it is classified as long staple cotton. There is short staple cotton, and there is extra long staple cotton, which is sort of like the Lexus of cotton. It’s in your fancy Egyptian sheets in your five-star hotel rooms.

There’s one particular species of cotton that makes up 90 percent or more of the global production of cotton. The long staple variety is the more desirable one, and in the Mississippi Delta, great energy was spent in trying to learn how to cultivate it, and trying to, breed varietals of cotton that would work well in the Delta.

Almost the entirety of the WPA Guide’s account of Greenwood has to do with cotton production. This was written in 1937, but the picture is not all that different from the antebellum period, in which the hard work of harvesting and processing cotton was entirely done by Black crews. And the cultivation of cotton and American blues music are intimately related to one another. One is a product of the other.

And while the blues goes back well before 1937, the picture of ginning cotton in the WPA guide hints at this intimate relation of music to cotton cultivation.

“The baled cotton goes from the gin to the compress where Negro handlers unload and pitch it to another set of Negroes, who bust the bands with the band breaker and throw it into the press. The Negroes work rhythmically, singing and shouting at one another. The compress runs by steam, and each time the plunger goes up with the bale, the press gives a snort and lets out a puff of white vapor, making the scene noisy and exciting.”

I’m willing to bet that every single American owns at least one article of clothing that is made out of cotton. But we are so removed from what it takes to produce cotton and what historically it took millions of enslaved Africans to accomplish.

Driving eastbound on US 82 towards Greenwood, you’re surrounded by vast fields of cotton, rows of telephone poles like crosses, repeat one another in gradually diminishing size towards the horizon. It is a characteristic vista in the Mississippi Delta.

It is beautiful, it is powerful, and it is also troubling in a certain way.

Or at least evocative of a very troubling history. I recently had a conversation with a musician friend who just returned from touring in South Carolina. And he said the mere sight of cotton fields in South Carolina creeped him out. Which is not an inappropriate response.

The language and the machinery of cotton cultivation in the 20th century will later play into one of the most horrific crimes in American history. But for now, heading east towards Greenwood, it becomes palpably evident that we are in the dominion of King Cotton. And his throne is in Greenwood.

Greenwood today is a dim shadow of its former days of glory. Empty storefronts line the main street. On this subdued Monday morning, I wander the streets of Greenwood, which possess a certain eloquence in their abandonment. I turn down one of the side alleys, paved with brick, looking for a spot that I stumbled into years before. A square Coca-Cola sign hangs from the stuccoed wall above the main entrance, which is a simple aluminum screen door. Next to it, a simple mailbox. Beyond the words Cotton Row Club beneath the Coke sign, there is nothing to indicate what is behind the front door. But I found out in 1999 when I pushed it open, to find a small room paneled in fake wood.

At several roundtables in the fairly modest space, people were playing cards. They turned to look at me as I came in. To my left, a vintage Coke machine, dispensed twelve-ounce cans of Budweiser and Miller Lite.

It was as if I had stumbled into a 1937 speakeasy, just with a Coke machine. The side-eyes from some of the card players indicated clearly to me that I was in the wrong place. Through the portal to that other world I had just stepped through, I backed back out onto the brick alley, only just beginning to make sense of what I had just seen. It was strange, to say the least.

But it is just one of Greenwood’s micro-cultures that still exist. When I first came here, it was still owned by Stacey Ragland, who started coming here in the 1950s. But this time, I don’t know who owns it, if anyone, and I have no need to enter that portal once again.

I’ve arranged to meet up with Wright Thompson and Dave Tell for lunch in Greenwood. We’re all here together for an event related to Emmett Till, and these guys know more about Emmett Till and they know more about Greenwood than just about anybody, especially the food. Wright Thompson is a writer for ESPN. But he also hosts a show with John T. Edge about food in the South. Dave Tell is the author of an excellent book about remembering and misremembering Emmett Till’s story.

We stop at the Crystal Grill on the corner of Carrollton and Lamar, downtown Greenwood. It’s been here since 1926. They both rave about the place, but it’s closed. So we head a couple blocks over to Downtown Subs and Wings, a fairly nondescript looking place. But it’s open.

It’s modest inside, but the food is fantastic. I’ve never had an Italian beef sandwich before. It’s a thing in Chicago. I only know about it because I’ve seen The Bear. I don’t have anything to compare it to. But if this is what an Italian beef sandwich is all about, then I’m in.

So much of the history of the civil rights movement is bound up with food and with restaurants. Think about the sit-ins at Woolworth lunch counters. Lester Maddox and the Pickrick Restaurant in Atlanta. Maurice’s Barbecue in Columbia, South Carolina. Aleck’s Barbecue and the Auburn Avenue Rib Shack, also in Atlanta. Restaurants have been the site of contests over civil rights for a long time. They’ve been where these battles were fought, planned for, mapped out and strategized.

Restaurants in the South are rarely just about food, especially ones that have been around as long as the Crystal Grill. After lunch, Wright drives us around Greenwood. He tells me about Baptist Town, the historically Black district of Greenwood, centered around the Black Baptist Church.

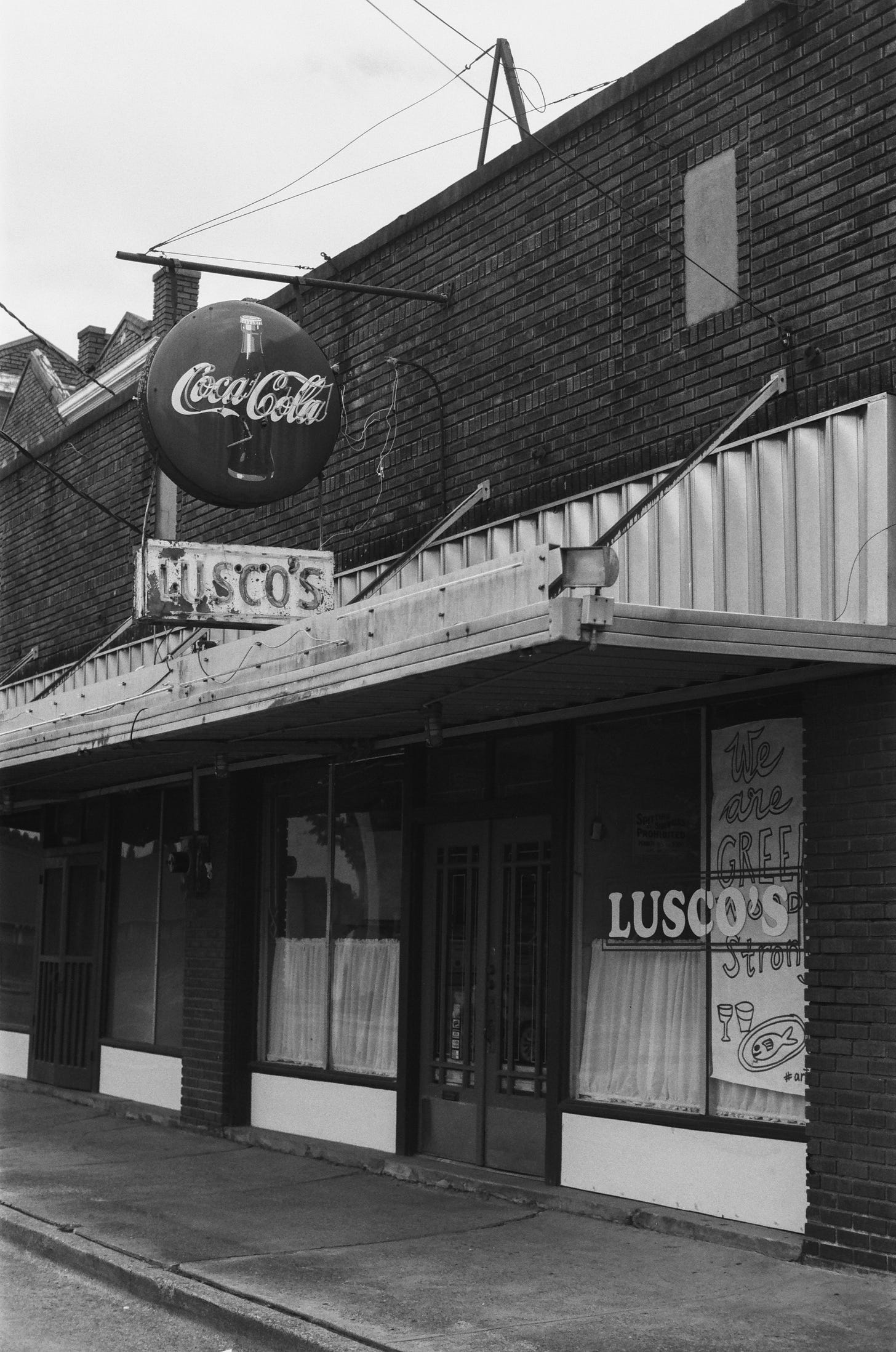

We drive past Lusco’s Restaurant. I’ve never heard of Lusco’s, but in this town, it’s a legendary institution. The doors are shuttered. It’s closed. It’s totally empty. The round red Coca-Cola sign and the Lusco’s name still hang above the awning. Apparently someone has expressed interest in buying the restaurant and moving it somewhere else.

They point me to a story about a waiter who worked here in the 1960s. His name was Booker Wright. In 1966, a documentary filmmaker called Frank DeFelitta, working for NBC, came to Mississippi to film a documentary called Mississippi: A Self Portrait. At one point in the film, he interviews Booker Wright. Dressed in a white dinner jacket, black tie and white shirt and black pants, Booker Wright runs through the menu at Lusco’s. There is no paper menu. It is all audible, and it is like a routine. It’s almost like a song-and-dance routine catered to the white customers at Lusco’s. A classic arrangement in the South in the 1960s: an all-Black staff serving an all-white clientele, and an all-Black staff dressed in formal wear.

And to be honest, it’s a little painful watching this because I’ve been to restaurants like this myself many, many times, including one I love in St. Simons, where for a long time, the waitstaff has looked exactly like Booker Wright. It’s been a few years since I’ve been back there, but at Benny’s Red Barn on St. Simons, there was a legendary waiter called Alvin who worked there for like 50-something years and the way this guy would deliver the menu was poetry. It was beautiful. But watching Booker Wright tell his story really drives home how little of Alvin’s story I really knew. And how much he probably had to hide from the customers who loved him.

But Booker Wright doesn’t just stop at a demonstration of how he reads out the menu from memory to his clientele. He goes on to talk about how some of these customers treat him, how some of them treat him with respect and some treat him with disrespect.

In the beginning of The Souls of Black Folk, W. E. B. Du Bois describes a fundamental characteristic of the Black experience as “double consciousness:”

“This sense of always looking at oneself through the eyes of others, of measuring one’s soul by the tape of a world that looks on in amused contempt and pity. One ever feels his twoness, an American, a Negro. Two souls, two thoughts, two unreconciled strivings, two warring ideals in one dark body, whose dogged strength alone keeps it from being torn asunder.”

Booker Wright is double consciousness in the flesh. He is the embodiment of what Du Bois is describing. While working at Lusco’s, he puts on a show. He puts on a happy face. He makes it clear how important it is that he smile at his customers, no matter how poorly they treat him.

In addition, Booker runs his own restaurant, called Booker’s Place, a few blocks away from Lusco’s, where he behaves as he wants to, where he can be himself, and not put on an act. In its day, Booker’s Place will be a haven for traveling musicians like B. B. King. It will be one of those restorative stops for civil rights workers. But when Mississippi: A Self Portrait airs in 1966, immediately, Booker experiences backlash. That night, Booker’s Place is burned. Booker himself is pistol-whipped by a local policeman and hospitalized. And seven years later, Booker himself is murdered by a disgruntled customer at his own restaurant.

Barely a month after the documentary film aired on May 1st on NBC, Stokely Carmichael was in Greenwood, as he had been numerous times as the leader of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC). He replaced John Lewis, the future representative from Georgia, in May of ‘66.

That summer in 1966 was the summer of James Meredith’s March Against Fear, a 220-mile march from Memphis to Jackson, in which Meredith, the first Black student admitted to the University of Mississippi, wanted to draw attention to the persistent racism in his home state. June 6th, James Meredith was shot three times with a 16-gauge shotgun by a white shooter named James Aubrey Norvell.

Meredith survived the shooting, but he was too badly injured to continue the march. So members from SCLC, including Martin Luther King, and members of SNCC, including Stokely Carmichael, took up the march.

Ten days after Meredith was shot, a crowd of about 600 had gathered in Broad Street Park in Greenwood. Carmichael had been arrested for putting up tents to accommodate the marchers who took up Meredith’s mission. The crowd included Charles Evers, who succeeded his late brother Medgar as director of the Jackson NAACP. According to Carmichael, Charles Evers “vowed never to set foot in Greenwood ever again because it was the hometown of Byron DeLay Beckwith,” his brother Medgar’s murderer.

As he tells the story, Carmichael writes,

“By the time I got out of jail, I was in no mood to compromise with racist arrogance. The rally had started. It was huge. The spirit of self-assertion and defiance was palpable. I looked over that crowd, that valiant, embattled community of old friends and fellow strugglers. I told them what they knew, that they could depend only on themselves, their own organized collective strength. Register and vote. The only rights they were likely to get were the ones they took for themselves. I raised the call for black power again. It was nothing new, we’d been talking about nothing else in the Delta for years. The only difference was that this time the national media were there.”

He told the crowd, “the only way we gonna stop them white men from whippin’ us is to take over. We’ve been saying freedom for six years and we ain’t got nothin’. What we gonna start saying now is Black Power!” When Stokely spoke to the crowd, chants of “Black Power” erupted from the audience. This was Stokely Carmichael’s rallying cry. While he had been using the term for some time, it was in Greenwood that he became forever identified with the slogan.

With it, he differentiated himself from Dr. King and the SCLC and eventually from the non-violent posture that had characterized the movement up to 1966. It signaled a new direction for SNCC and for the movement itself. And to some, he took SNCC in a more radical direction than his predecessors had. Of course, the term freaked out a lot of white people who, for decades, had been fantasizing about a racial uprising, a militant Black takeover of American society.

I don’t know if Stokely Carmichael knew the story of Booker Wright. It’s almost impossible to imagine that he didn’t, as well as he knew Greenwood and particularly the Black community in Baptist Town. It’s possible he even ate at Booker’s Place. We know that he didn’t eat at Lusco’s because they didn’t serve Black people in 1966. But against the backdrop of the Booker Wright story, Carmichael’s call for Black Power was really quite simple. It was a refusal of the kind of double identity, the double consciousness that Du Bois described in Souls of Black Folk, and which Booker Wright embodied in his life, and articulated so powerfully in Mississippi: A Self Portrait. If all the power remained white in Greenwood in 1966, there was little room for freedom among the Black community.

Black power meant black empowerment. Carmichael and others had identified racism in American society as institutional, as structural, as systemic, not simply a personal attitude or disposition to people of different colors. It meant a refusal to continue waiting on white authorities and white power to come around to see the light, as it were, to accede to Black demands for basic civil rights, to be treated with a basic human dignity. The freedom not to have to constantly wear a fake smile in front of white people. There is, of course, more to it than this.

And while Stokely Carmichael and Dr. King are often pitted against each other, they were actually a lot closer to one another than it might seem. Especially to white people who tend to want to imagine King as the inspiring orator on the steps of the Lincoln Memorial, the King of the “I Have a Dream” speech, and not the King who protested poverty as much as militarism, as much as white supremacy.

Stokely Carmichael was from Trinidad, originally. But in the Delta, he discovered something about himself. He found a new voice.

I was struck myself by the parallels between Stokely Carmichael’s experience of the Delta and my own. We come from completely different backgrounds. But when I read his account of what it was like to experience the Delta the first time, he used a word that I had used myself, without ever knowing that he had used it before.

In his memoir, Ready for Revolution, he writes,

“The Delta itself was not to be believed. Day after day, you could sit in the middle of it and not believe what you were seeing or hearing. The landscape was my first experience in unlearning. It was unlike anything I’d ever encountered, quite literally one vast, flat, unbroken cotton and soybean plantation.”

The one word that captures the impact the Delta made on Stokely Carmichael is unlearning. It is a land that forces you to give up your pretensions, to give up some of your dearly held mythology about yourself, about the country in which you find yourself.

Its stark landscape seems to present a duality of choices, either truth or illusion. It is a kind of confrontational landscape: the horizon line that stretches across the Mississippi Delta seems to divide the world into two halves. And similarly, to put before any visitor to the Delta a choice between willful ignorance and a learned ignorance.

That kind of unlearning that Stokely Carmichael described: the act of yielding up what you think you think, or what you think you know. What I thought I thought before I came to the Mississippi Delta the first time I'm sure is quite different than what Stokely Carmichael thought he thought. And what I have to unlearn is probably different than what he felt he had to unlearn.

* * *

The WPA Guide describes Greenwood much as Robert Johnson would have experienced it in 1938. Johnson, the king of the Delta blues, spent his last night alive in Greenwood. Robert Johnson wasn’t the only person who spent the last night of his life in Greenwood, Mississippi.

On August 27th, 1955, Mose Wright, Maurice Wright, Wheeler Parker, and Emmett Till drove down to Greenwood from Money “for an evening of fun.” As Devery Anderson writes,

“While Mose visited his own friends gathered at the railroad tracks, the boys walked the busy streets, gazed at the nightclubs, and looked with amazement at the large crowds that had gathered that night…For the Chicago boys, it was a nice break from the isolation of East Money. They left Greenwood after midnight and arrived back home around 1:00 am.”

It would be the last night of fourteen year-old Emmett Till’s life.

NOTES

The July 1979 issue of American Cinematographer, devoted to The Muppet Movie.

Dave Tell, Remembering Emmett Till (Chicago: University of Chicago Press 2021).

Wright Thompson is currently working on a book about Emmett Till. His most recent book is Pappyland: A Story of Family, Fine Bourbon, and the Things That Last (New York: Penguin Publishing Group 2023).

Devery Anderson, Emmett Till: The Murder That Shocked the World and Propelled the Civil Rights Movement (Oxford, MS: University Press of Mississippi 2017).

Watch Wright’s program with John T. Edge, True South, on ESPN.

Stokely Carmichael, Ready for Revolution: The Life and Struggles of Stokely Carmichael (Kwame Ture) (New York: Scribner 2005).

Debbie Elliott, “A Musical Tribute For A Waiter Who Spoke Out Against Racism,” NPR Weekend Edition Saturday, November 29, 2014

Watch Booker Wright’s interview for Mississippi: A Self-Portrait (1966):

See the documentary film about Booker Wright, Booker’s Place: A Mississippi Story (2012):

The Streets of Greenwood, a 1963 documentary depicting the town at the height of its centrality to voter registration in the Delta during the Civil Rights Movement: