That’s Not It

The first time I didn’t see the Mississippi Delta was in 1997. My friend John and I were on the first of what became multiple tours of the southeast. We had very little in the way of a plan of where we were going, except we knew that we wanted to make it to New Orleans. We weren’t sure how we were going to get there, but when we did, we headed due south on Louisiana Highway 23, which runs right beside the Mississippi River all the way down to Venice, towards the Gulf of Mexico.

So back to my story about not quite seeing the Mississippi Delta. We’re driving down Louisiana Highway 23. If we go all the way, we’ll end up in the Gulf of Mexico. I mean, I had a high school college and graduate school education. I thought I knew what a “delta” was: where a river empties out into a bigger body of water, like the Nile Delta.

I mean, I learned that in fourth grade geography. So we drive down Highway 23, looking for the Delta. It’s dark. There’s an electrical storm in the distance. We pull up on the levee in John’s 1977 Ford pickup, which I don’t think we’re supposed to do, lightning illuminating the interior of clouds miles away.

I don’t know if we made it all the way down to Venice on that attempt, but I now know that what we did not see on that journey was the Mississippi Delta. It wouldn’t be for another couple years until we did see what actually is the Mississippi Delta, which isn’t really a delta in the technical sense, or at least in a sense that would satisfy your fourth grade geography teacher. It’s not where a river empties out into a bigger body of water. There’s some emptying that goes on in the Delta. But you could be forgiven for thinking that it was at the end of the Mississippi River where it becomes the Gulf of Mexico. But that’s not the Delta.

The Mississippi Delta is a region of the state that is bordered by the Mississippi River on the west and the Yazoo River on the eastern side. In between is this vast alluvial plain where rivers, including the Mississippi, have overflowed for millions of years, leaving deposits of rich nutrients that constitute some of the most fertile soil on the planet.

The Delta is not what I thought it was. And even after repeated visits to the Delta, it manages to exceed or transcend my grasp. It’s a mysterious, elusive place. The Delta did then and continues to upset my idea of what I think I know. And, fittingly, it eluded me on my first attempt.

We came close that trip. We made it to Vicksburg, which is traditionally thought of as the ending or the beginning point of the Mississippi Delta. The author David Cohn, who was from there, said that “the Mississippi Delta begins in the lobby of the Peabody Hotel in Memphis and ends on Catfish Row in Vicksburg.” But David Cohn also called the Peabody “the Paris Ritz, the Cairo Shepherds, and the London Savoy of this section.” He was a little prone to exaggeration. Still, it’s a great line that everybody who writes anything about the Delta feels obligated to cite, misquote, plagiarize, remix, or butcher. But anyway, now it’s assumed practically the status of a biblical proverb.

Well, eventually we found the Delta, but on that first trip in 1997, we brushed by it. Even then, we didn’t know what we were missing, or what we were just barely brushing up against.

The Delta Proper

It wouldn’t be until 1999 that we descended into the Delta proper. And I say “descended,” because it actually does require a descent in elevation. Depending on which direction you approach it from, you’re going to go down in elevation, not up. Most prominently in Yazoo City, where there’s a steep hill from a bluff above the Delta into Yazoo City itself. And you really get a profound sense of the Delta as a lowland, which is both a metaphorical and a literal reality.

I mention this story because it illustrates something I want to communicate about this region: that even somebody who has read books, who’s lived their entire life in the South, might not really get what the Mississippi Delta is (and by extension, the region itself, The American South).

I came back from that trip telling my father that we had crossed Lake Pontchartrain. Which, he gently corrected me, was not actually pronounced like a French word by a person who thinks he can speak French, but is, of course, pronounced like Lake Poncha-train.

The spinal cord of American music

We approached Vicksburg from the south, coming up US 61, that famous highway that runs up through the Mississippi Delta along the Mississippi River all the way up to Chicago. It’s a famous highway that connects the Delta blues with the Chicago blues. It’s like the spinal cord of American music, from New Orleans to the Mississippi Delta to St. Louis all the way up to Chicago. And for those Black Americans in the early 20th century who owned a car, Highway 61 was like an evacuation route out of the oppression of the Jim Crow South, for the promise of a new start somewhere else. US 61 doesn’t actually go into Chicago. It runs a little bit to the west, but it will get you close.

During the Great migration from around 1915 to 1940 or so, millions of Black Americans escape the South for places like the Midwest, the West coast, the Northeast, and they did so without interstates. The roads were a lot different in the 1910s and 1920s. In some cases, they were horrible, little better than gravel roads.

So US 61 begins—appropriately—near the Storyville neighborhood in New Orleans. Now, much of it is a four-lane divided highway that looks a lot like an interstate. And along the way, the old route of Highway 61 weaves back and forth across the new route. So if you’re traveling this route, if you decide to take a road trip along US 61, you’ve got to follow Old 61, where it takes you to some of the small towns you would miss if you just stayed on Main US 61.

So on my first trip up this storied highway, I had very little sense of the thousands and even millions of pilgrims who traveled this route before me. I at least know that US 61 has something that current interstates don’t. It has a certain kind of gravitas, a history, a powerful story that connects America together in much the same way that the Mississippi River binds the nation together geographically, culturally, and so on.

Interstates are not evil, but they kind of are

We have a fundamental rule on our trips to stay away from interstates. But at Vicksburg, the only way to cross the Mississippi River is via Interstate 20, which lands you on the Louisiana side of the river in a town, ironically, called Delta. In a way, it is the southern terminus of the Mississippi Delta, even though it’s on the Louisiana side.

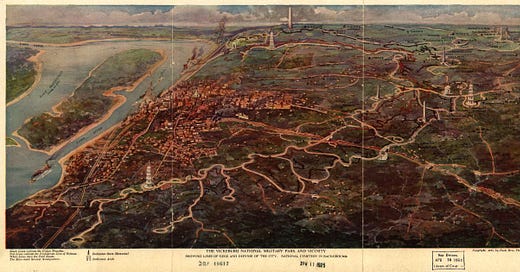

At Vicksburg, a high bluff overlooks the river. We pause at Riverfront Park and look south, down the river. A steamboat silhouetted against a yellow sunset, the river displaying all of the majesty and grandeur for which it is rightly famous. It is difficult to stand on the precipice of this most significant body of water in the continental United States and not feel a sense of awe, a sense of humility, and the kind of wonder that at least 40 percent of the land in America touches the Mississippi River in some way.

It is unbelievably huge. The drainage basin of the Mississippi River goes from the Rocky Mountains in the west to the Allegheny Mountains in the east. It makes up 1.15 million square miles of the continental United States. It is enormous. An astonishing amount of water passes in front of this bluff every day.

It’s hard to compass just how important this river has been for American life, and how much mythology has been attached to it. It’s easy to see why. It’s just impressive. It’s vast, it’s deep, and it’s got lots of secrets.

Now, I grew up in Atlanta, Georgia, but Vicksburg is a different kind of South. It’s steamboats and antebellum mansions with white columns and indulgent front porches. It seems, on the surface, to fit all of the stereotypes, like the cover of a bad romance novel set in the 19th century. At least it seems that way, at first.

Not quite finding a story of the South, or myself

So my story of Vicksburg is about coming close to, but not quite connecting with, the story of the South, and by extension, with myself, my own story. What any of this traveling the South will have to do with me would lay twenty years in the future. It wouldn’t be for another two decades that I would begin to piece together why any of this matters, what this history, this legacy of suppression, of theft, of willful amnesia, has to do with my history. But for now, Vicksburg is gorgeous. As I stand on the bluff in Vicksburg, the sunlight off the Mississippi River turning from golden to amber to a deep orange. It is easy to see why this river has been so mythologized.

I take a photograph from the bluff of the scene, looking south down the river, over the I-20 bridge, which is industrial and elegant in a prosaic sort of way. Between me and the bridge, a steamboat muscles up the river, three small lights on its bow, like the first stars of deepening twilight.

But I grew up in Atlanta, Georgia, where indifference to the past was practically the city’s motto. And as brilliant as the city has been at marketing itself, it has never really marketed its Civil War history. There’s not a great deal of it, to be honest. Gone with the Wind notwithstanding, Atlanta’s role in the Civil War, while important and significant, is not the source of its tourism. There are not a ton of Civil War sites, apart from The Cyclorama, to go visit in Atlanta.

And it doesn’t market itself that way. Vicksburg, by contrast, is one of those Southern cities that is very conscious of its own history. And its prominence as a port on the Mississippi River made it a strategically desirable city for both the Confederacy and the Union. So Vicksburg’s fortunes were, and remain, bound up with the Civil War.

It’s one of those primary stops on Civil War tours. It’s so written into the history of the Civil War, you can practically not even say the word “Vicksburg” without sounding like Shelby Foote. And Vicksburg was obviously a very important city during the Civil War. It was important to control of the lower Mississippi River.

There’s been a National Military Park here in Vicksburg since 1899. There’s a National Cemetery, and plenty of other Civil War monuments around town. Which is all fine if you’re into that sort of thing. For me, personally, the Civil War gets way too much airtime in Southern history, and in Southern culture, and Southern tourism, and all the rest.

Which is why the WPA Guides are often refreshing to read. Not that they don’t talk about “The War between the States” and often in decidedly one-sided terms, but their discussion of the Civil War is often tempered or balanced by a deeper dive into pre-Civil War and post-Civil War history—shocking for many Southerners who might be surprised to learn that there is a history to the South before and after the Civil War.

The WPA Guides are the Best Travel Guides Ever Written about the U.S.

The WPA Guides were written in the 1930s and early 40s, and they definitely betray the prejudices of their times, and sometimes are condescending in the way they speak of “Negroes,” as most of the Southern guides do. But they often contain pictures that are less rosy, less whitewashed, and less sentimentalized than the packaged versions of Old South tourism would like to pretend Southern history to be.

For example:

“Like a strenuous boy, Vicksburg suffered violently from the pangs of eating too well and growing too fast. With trade and expansion came speculation, embezzlement, and graft. With prosperity came lawlessness and vice. The scum of the river gamblers gathered at the foot of the walnut hills and became an open menace. Wagon drivers, more often white farmers conveying their whole crop into Vicksburg in a single wagon, hated broadcloth coats and tall beaver hats. They wore coarse, dingy yellow or blue linsey-woolsey and broad brimmed hats, and with long rawhide whips in their hands and plenty of whisky under their belts, they blustered and roared through the town. Flatboatmen joined the wagoners in their blustering and the young professional gentlemen in their gambling. These “ring-tailed roarers” from the river spent their working hours fighting swift currents and hairpin bends, and their time on shore swearing they could ‘throw down, drag out, and lick any man in the country,’ and proving it. Beatings, knifings, and shootings occurred daily, and women appeared on the streets at the risk of insult.”

Now that sounds like a town with some life in it. If one I’m not exactly itching to go visit.

The WPA Guides are, it is not controversial to say, the best travel guides ever written about the United States.

But they’re not travel guides in the contemporary sense. You won’t find any information about hotels, B&Bs, good restaurants, or good places to get in trouble. There’s also plenty that the WPA Guides don’t say. Of course, no book can say everything. But they often do say more than historical markers might.

Case in point: The Guide to Mississippi recounts an episode in 1875 that is, as far as I can tell, unmarked in the city of Vicksburg today. It was actually 1874, but let’s leave that aside for a moment. And while the WPA Guide gets some of the details slightly wrong or slightly misleadingly, the gist of the episode is there.

And that’s worth noting because it’s not a very flattering episode. So after the Civil War, the Reconstruction Amendments were passed—the 13th, 14th, and 15th Amendments—which represented what has often been called a new birth of freedom for the country, especially for its Black citizens. Black men were now serving in elected office in a way that they had never done before.

John Lynch was the first Black person that Mississippi sent to Congress in its history. That was in 1873. And Mississippi would not elect another Black Congressperson until 1987. This sort of thing was happening everywhere in the South from the late 1860s and early 1870s: Black men, who years before had been enslaved, were now serving an elected office. To many whites, this didn’t go over very well, and it provoked massive, often violent resistance. The Ku Klux Klan was formed in Pulaski, Tennessee, as a response to this new enfranchisement of Black Americans. After it was officially outlawed by the federal government in 1870 and 1871, new groups spawned around the southeast, including the White Shirts in Mississippi, and the Red Shirts in South Carolina.

The Vicksburg Massacre

So in 1874, Vicksburg had a Black sheriff. His name was Peter Crosby. He was 30 years old, a veteran of the Union Army.

And the position of sheriff at the time wasn’t just about law enforcement; the sheriff was also the tax collector. So, there were a lot of people in Vicksburg who were not happy with Crosby’s election—and he was duly elected.

So, there were a fair number of white people in Vicksburg in 1874 who were not happy with having a Black sheriff. They took it as an in-your-face kind of insult. This was, after all, a “white man’s country.” Black men weren’t supposed to be officers of the law, in their view.

The summer of 1874 in Vicksburg was tense. You had an upcoming election in the fall. July 4th was the anniversary of both American independence and the end of the siege of Vicksburg in 1863, which was something of a victory for Ulysses Grant.

It had seemed like an almost impossible feat. Vicksburg was this impregnable city on a bluff, and it was under siege for 47 days in 1863, until it finally surrendered on July 4th to General Grant. So here, eleven years later, Grant is President, and in the summer of that year, Vicksburg appears to be under siege again.

Armed white men are marching throughout the streets daily in Vicksburg. So on July 4th, Black Republicans are holding a celebration in Vicksburg, and a group of white men show up with guns and start firing them. They go on what Nicholas Lehman calls an “open-ended rampage.” The next day, Crosby appeals up the chain of command for President Grant to send in Federal troops.

In a weird way, it’s kind of a reprise of the siege of Vicksburg in 1863. And Grant is once again at the center of it. He decides not to send in troops. And this pattern repeats itself a number of times. But Grant’s refusal to get involved to send in Federal troops only gives local white militias, paramilitary groups, the white league, the white liners, all these white terrorist groups, implicit license to do whatever they want. Their purpose is to secure the election for white democrats, which means intimidating, pressuring, or even killing Black men. Which they do.

But jump ahead to December of 1874. Democrats have won all the local elections in a majority Black, majority Republican state. There’s still a Republican governor, called Adelbert Ames, whose position is increasingly precarious, as is Peter Crosby’s.

It’s a complicated story, but by December, Crosby’s leadership as sheriff is practically untenable. With renewed vigor, these white groups pressure Crosby to resign. So they’re calling themselves the Taxpayers League. And under the pretext of objection to the way taxes are being collected and spent, a group of more than 500 white men march to the courthouse and demand Crosby’s resignation.

He wasn’t about to take this lying down. It’s unclear exactly who’s responsible for it, but someone begins circulating to the Black community in Vicksburg these printed cards with Crosby’s name on them, calling them to resist this white intimidation. That Sunday, Black preachers read out the text of this note to their congregations.

Well, the word gets around, and members of these local white militias smell an uprising. “Maybe this is it, maybe this is the race war that we’ve been hearing about, we’ve been trained to fear and be paranoid about by local newspapers.” They show up in the streets of Vicksburg, with guns. And in the process, there’s this tense standoff on a bridge on the south side of Vicksburg: white militias on one side, Black men supporting Sheriff Crosby on the other. And of course, each of them representing a larger attitude or position with respect to this whole project of Reconstruction, this whole attempt to enfranchise and empower Black citizens. They come to what appears to be a truce.

Andrew Owen, the leader of the Black group, tells everybody to go home. As he’s walking away from the white group, one member of the white group fires a shot across the bridge. Someone in Owen’s group asks if they can return fire. He replies, “no.” He insists that his group go home.

Governor Ames’s wife wrote to her mother and described this episode as “a simple massacre.” And of course, it doesn’t end there. It’s a weird sort of replay of the Siege of Vicksburg in 1863. Black men are now using the old breastworks built by the Union Army for their own protection. It’s like a warfare situation. By the next morning, somewhere around 30 Black men have been murdered. There are no white fatalities. The Vicksburg episode is described as a “riot” in the Southern press and as a “massacre” in the Northern press. The WPA Guide may get some of the finer points slightly off, but to its credit, it doesn’t ignore or suppress or attempt to whitewash this episode. It puts it right out there. It’s an emblematic instance of something that will repeat itself over and over again, across the region.

This “new birth of freedom” experienced by Black Americans provokes a violent white Backlash that leaves Black men dead and restores white men to power. After 1875, white supremacy’s hold on power in Mississippi would become unambiguous, and it was not unrelated to episodes like the Vicksburg Massacre, through which white terrorist groups effected profound and lasting political change.

As I mentioned earlier, there is no marker to the Vicksburg Massacre today. If you wandered around the courthouse, if you wandered around downtown Vicksburg, you wouldn’t find any indication of this ever happening. This, of course, isn’t the whole story of Vicksburg, but it’s an important part of it.

And this isn’t the end of this story either. But there’s another place I want to check out. So before we head north into the Delta, let’s take a detour south on US 61.

A Detour, South on US 61

Not far down the road, you’ll see an historical marker to Briarfield and Hurricane Plantations. They’re, of course, not there anymore, and if you wanted to go visit the site where they once were, you’d have to cross I-20 over the Mississippi River into Louisiana, head down Louisiana 603, and eventually wind your way onto a little island called Davis Island.

Now, if you look at a map, this will give you some idea of just what we’re dealing with here, because the Mississippi runs not exactly in a straight line, but in a fairly consistent path southwards from Vicksburg. But there’s this big loop in the state line that loops up north, and then to the west, and then comes back around south, around what is called Davis Island.

The Mississippi River, and the border between Louisiana and Mississippi: they don’t always line up. Because while maps, and cartographers, and land surveyors, and the Department of the Interior like for borders to stay in one place, The Mississippi doesn’t really care. So often if you follow the route of that border between these two states, it will go in what seems like a totally random direction.

If you look at a map of this area, south of Vicksburg, it looks like a gerrymandered political district. The island that is called Davis Island—there’s even a portion of it that is in Louisiana, the rest of it is in Mississippi, even though it’s on the western side of the Mississippi River. But from 1827 onward, a huge plantation existed in this area called Hurricane Plantation.

It was over 4,000 acres, owned and operated by Joseph Emery Davis. He had over 300 slaves. He was one of the richest men in Mississippi. And according to scholars, he ran an unusually benevolent practice. He fed the people enslaved on his property decent food. They lived in decent structures. He had a jury system established on Hurricane in order to adjudicate disputes between the people that he had enslaved. It was an unusually progressive system for a plantation in Mississippi in 1830.

Supposedly, Davis was inspired by the example of Robert Owen, who was a social reformer from Wales during the Industrial Revolution. He tried to implement some of these utopian socialist ideals onto his plantation in Mississippi. The great historian of Reconstruction, Eric Foner, called Davis Bend “the largest laboratory of Black economic independence.” And this was before the end of the Civil War.

And in April of 1862, advancing Union troops made Davis think it was a good idea to leave Hurricane Plantation. He left Hurricane under the supervision of an enslaved man called Benjamin Montgomery. During the Civil War, Davis Bend was occupied by Union troops. And General Grant (future President Ulysses Grant) wanted to make Davis Bend a “Negro paradise,” a kind of experiment of Black self-government. So this is essentially land confiscated and turned over to a noble purpose.

You all know what happens before the end of the Civil War: Abraham Lincoln is assassinated, Andrew Johnson from Tennessee becomes President. Johnson is finding fewer and fewer fans. The Radical Republicans can’t stand him, the rich planter class can’t stand him either. He seems like a turncoat, he tries to play it both ways, and he is just a train wreck of a president.

But he wants to give confiscated land back to the landowners. And even though Joseph Davis intentionally gave his property to Ben Montgomery to run, the Federal government ended up giving it back to Joseph Davis in 1866. But Davis sold the property to Ben Montgomery anyway, and so there’s this really unusual situation where a formerly enslaved man of African descent is now running one of the largest plantations in Mississippi.

In 1867, the Mississippi flooded, and as it has done so many times in its history, decided to change course. So instead of looping around what was then Davis Bend, it headed more or less in a straight line south, making what was once just a big bend in the river connected to the mainland, now an island cut off from it. Hence, Davis Bend became Davis Island. Joseph Davis died in 1870. In 1878, in a strange but not uncharacteristic move for the period, the State of Mississippi restored the land to the Davis family, thus, as Eric Foner says, “bringing a melancholy end to the dream of establishing a Negro paradise at Davis Bend.”

Joseph Davis’s More Famous Brother

The story of Hurricane Plantation and Davis Bend does not end there, however. But for now, we’re going to head back north towards Vicksburg. And along the way, I want to tell you something else about Joseph Davis. He had a very famous younger brother called Jefferson, who also ran a plantation at Davis Bend called Briarfield, which was a thousand acres that his older brother Joseph gave to him. Jefferson, of course, became the President of the Confederate States of America.

At least in terms of what we know about how Hurricane Plantation was run, Joseph Davis doesn’t exactly fit the stereotype of the domineering, violent, retributive, vicious slave master. Before we elevate Joseph Davis, though, as some sort of progressive, enlightened hero, as countercultural as his methods of running a plantation may have been, Joseph Davis had a vested interest in the institution of slavery, became one of the wealthiest men in Mississippi, became an outspoken advocate for the institution and for so-called “states’ rights” from the 1840s onwards. He was still an enthusiastic apologist for slavery, and made a fabulous fortune off of it.

At the same time, the legacy of Hurricane Plantation would bear fruit in the Mississippi Delta, in one of the oldest Black settlements in the United States. We’ll get to that when we get there. In the meantime, there’s a reason I brought you here.

I started a little road trip through the Mississippi Delta by going in the opposite direction. It’s literally disorienting. I told you we were going to go north, we’re going south. I told you we were going to go into the Delta, we’re going south of Vicksburg. But this kind of disorientation is important, and it’s good to do it here at the beginning, because it’s going to happen a lot on this trip.

Things are not going to be like you think they’re going to be. That much I can tell you. So you’re standing on the Mississippi side of the river, looking across it at what you think is Louisiana. It makes sense that that should be Louisiana. It’s on the other side of the river. That’s a different state, but it’s not. It’s still Mississippi. And in fact, a part of Mississippi that has a pretty incredible story that you might not know about unless you happen to pass this historical marker on the side of the road on US 61 south of Vicksburg, and if you bothered to read it, and that opened up a curiosity about what else is going on here.

This is the stuff that The Detourist is made of. This is the kind of thing that we’re going to be stumbling into time and again. These kinds of signs, these kinds of stories, they’re not on the main drag. They’re not on the interstate of American history. And in the case of episodes like the Vicksburg Massacre, they don’t even appear to be anywhere.

The stories I didn’t learn in elementary school, junior high school, high school, college, even graduate school about my region’s history. In fact, the stories I didn’t learn about my own family’s history are some of the most interesting stories there are.

And it’s not just that they’re more interesting stories, it’s that they make us who we are far more than we acknowledge. Why you and I didn’t hear those kinds of stories? Well, that’s one of the things we’re going to explore on the road ahead. So here we are, our first foray into the Delta. We haven’t actually made it into the Delta yet, but I promise you next time we’re going to get there.

And this story that I’ve told you about Hurricane Bend, it has another chapter. And in fact, it kind of illustrates a fundamental principle of The DETOURIST: Stories don’t ever end. See you next time.