Foster's Children

A row of rental canoes lays unlocked and belly-up on the bank of the swamp canal at Stephen C. Foster State Park at the southern edge of the Okefenokee. Whoever left them that way seemed to assume that no one in their right mind would take a joy ride in one of them, much less haul one off in the back of a pickup truck. “Proceed at your own risk,” they seem to warn to any fools dumb enough to try and venture out in a stolen swamp boat. The presence of the crane seems to offer one final chance to turn back, until it takes flight from the water’s edge, a trail of swamp water falling from its drooping feet, as if washing its hands of the world to come. We read this like a telegram: “You’re on your own, brother.”

The aluminum boat turns over with ease and lithely slides into the water. It shimmies as we step into it, bracing the gunwales with every available hand. We shove off the bank, the boat steadied, and paddle in silence into the narrow canal leading into the swamp. Lily pads line either bank, and creep out into the thin passageway. What the hell are we doing, I wonder aloud. I haven’t operated a canoe since summer camp on a pond in North Carolina in the 1980s, and there the water was so shallow that if you fell out you could stand on two feet and hoist yourself back in again. But here the water is motionless as death, so who knows when, if ever, you will reach bottom.

The Okefenokee is a different world. It’s beauty is unlike anything I have ever seen, especially in the calm, unpeopled twilight when the sense of being far, far away is palpable, increasing even with each minute of fading sunlight. It is a cliché to say that the water is as black as molasses but that’s exactly how it appears: impenetrable and viscous. There are people, I am sure, who would not hesitate to dip their hand into it. But not me: I am content to imagine that if I were to do so, and lick my fingers, they would taste like sorghum syrup.

We come to a stop in the middle of the river. The eyes of no fewer than nine alligators peer suspiciously at us from just above the surface. Water snakes course a sinuous trail towards the reeds. I am sure people have fallen into the Suwannee many times before, and I don’t even think gators eat humans, but I know that alligator snapping turtles eat anything that moves. I am not about to test the “they’re more scared of you than you are of them” thesis, so my canoeing form is more on point than ever.

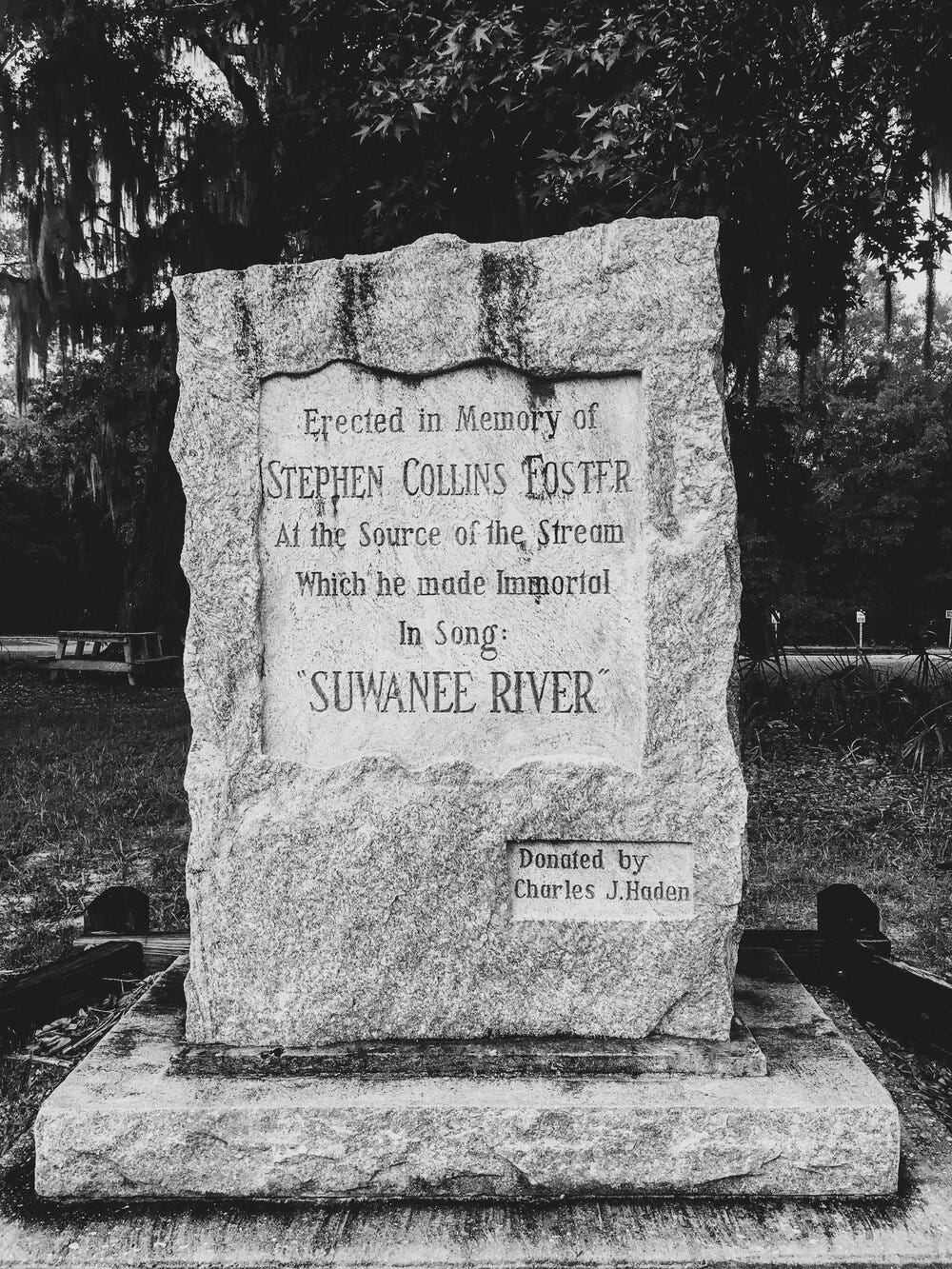

It is almost as dark as the river itself when we row back to the boat basin, haul the canoe back on to the bank, and turn it over, belly-up like we found it. The air is thick and resonant, reverberating with deep calls of wild creatures, some of whom still may not have names. But in this region of south Georgia and north Florida, one name pops up over and over again: Stephen C. Foster. The state park that serves as a main portal into the strange world of the swamp is named for him. So is a cultural center a little further south, in White Springs, Florida. A small stone monument in Fargo stands near the river he made famous and probably never saw.

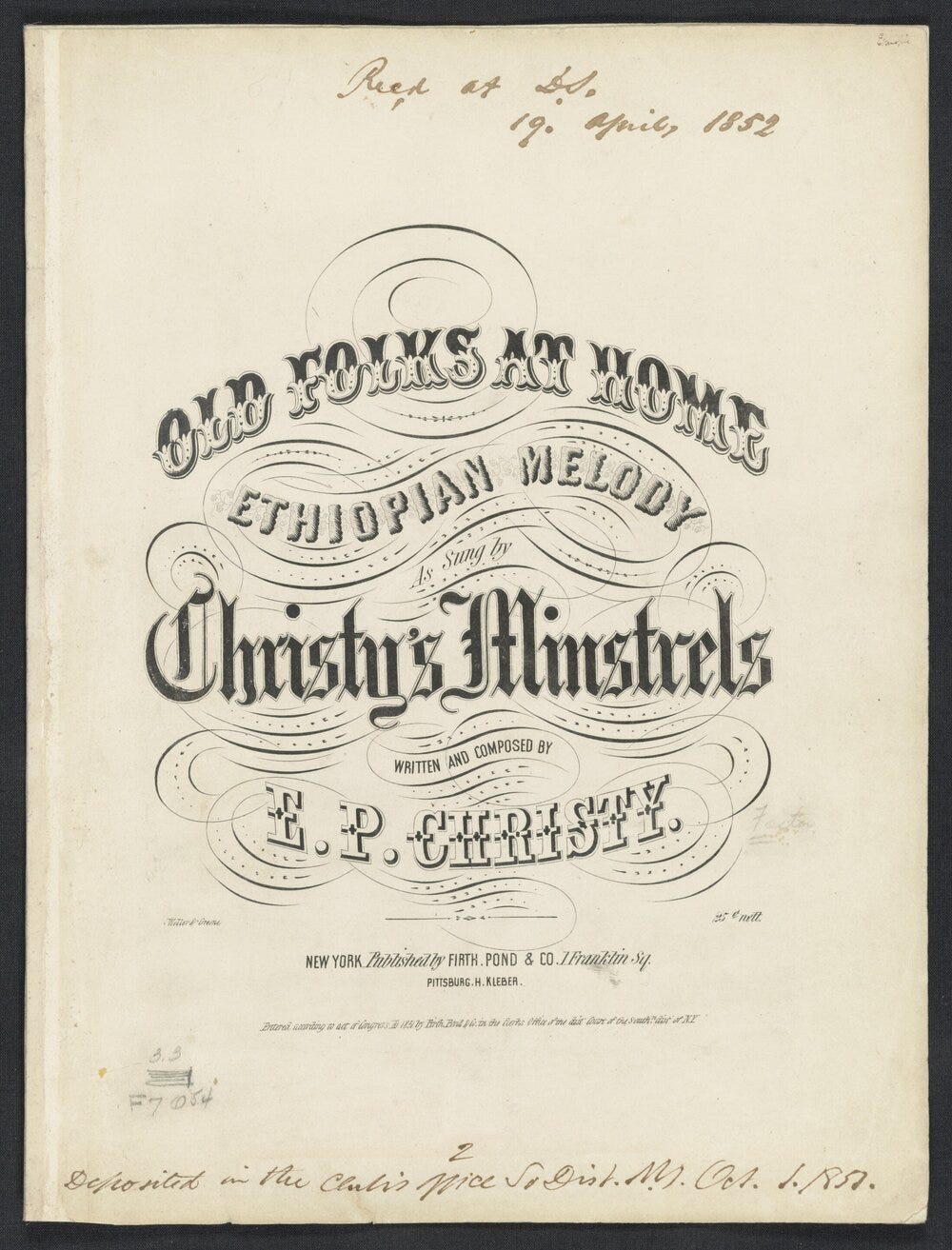

Stephen Foster was a justly famous nineteenth century songwriter with a penchant for place: “I come from Alabama with a banjo on my knee,” “the sun shines bright in my old Kentucky home,” and so on. Foster wrote songs in character, which is important to remember, because he didn’t come from Alabama and sure as hell not with a banjo on his knee, he had no Kentucky home, and he never once set foot even remotely close to the park named for him. Almost every school kid in America knows Foster’s music, even if they don’t know his name. He wrote songs for minstrel shows and living rooms, and his lyrics frequently conjure up images of a “simpler” past, when families were together. Case in point: “Old Folks at Home,” a tune he wrote in 1851, and the song entirely responsible for his fame in south Georgia and northern Florida.

Way down upon de Swanee Ribber,

Far, far away,

Dere’s wha my heart is turning ebber,

Dere’s wha de old folks stay.

All up and down de whole creation

Sadly I roam,

Still longing for de old plantation,

And for de old folks at home.

The water here seems barely to move at all. It becomes clear Stephen Foster never saw it, because his lyrics have nothing to do with a real place and everything to do with a white abstraction.

All de world am sad and dreary,

Eb-rywhere I roam;

Oh, darkeys, how my heart grows weary,

Far from de old folks at home!

“Old Folks at Home” is written in the voice of a slave pining for south Georgia (or north Florida). It’s a romantic vision of exile, written the way a white man might imagine an enslaved person longing for home. It’s like “Dixie” written for slaves.

Foster wrote the song at the behest of E. P. Christy, leader of Christy’s Minstrels, a prominent and very successful blackface group based in New York who held a standing nightly gig at Mechanics Hall, a building they owned on Broadway. Foster sold the tune and authorship to Christy for the troupe’s exclusive use. The “Ethiopian Melody” became a sensational hit, and vendors of the sheet music struggled to keep up with voracious demand. By May it was already in its tenth edition. One merchant in Buffalo said in June 1852 that the song had “already met with immense sale and is considered far ahead of anything in the Ethiopian way ever published.” (In 1919, George Gershwin, along with lyricist Irving Caesar, wrote his own semi-parody of Foster’s song called “Swanee,” made famous by America’s most famous blackface performer, Al Jolson, who recorded it in 1920. It was the most popular single Gershwin ever wrote.)

“Old Folks” was so fantastically successful that it became a canonical item in American popular culture—so much so that after composing his Symphony No. 9 (“The New World”), Czech composer Antonín Dvorák wrote an arrangement for “Old Folks” which he debuted and conducted at a charity concert in Madison Square Garden in January 1894. Dvorák, who was a studious devotee and apologist for folk music, thought of “Old Folks” as genuine “negro music.” Some reviewers were wise to the category error, but some African-Americans embraced the song as a faithful, or at least not egregious, expression of Black sentiment. W.E.B. Du Bois thought of the tune as exemplary of the way “the songs of white America have been distinctively influenced by the slave songs or have incorporated whole phrases of Negro melody.”

Critics today might say that “Old Folks” “co-opted” or “appropriated” Black musical motifs instead of “incorporating” or being “influenced” by them, but Du Bois was wise to the fact that “Old Folks” belonged principally to the songs of white and not Black America. This has not stopped both Black and white artists from continuing to perform and record it—although more often than not white ones. In this way, it is an important artifact of American culture, in the way the song has been continually reworked, un-worded and re-worded, re-arranged and revised (in the literal sense of “seen again”). The song has been recorded and reimagined by artists from Louis Armstrong, Paul Robeson, Big Bill Broonzy, Chuck Berry, Gene Krupa, The Dave Brubeck Quartet, Mark O’Connor, Itzhak Perlman, The Robert Shaw Chorale, The Mormon Tabernacle Choir, and even the Beach Boys. There is, apparently, something in this music that generations of musicians find worth coming back to, worth arguing about, worth revising.

There is no question that “Old Folks” is a truly great melody. Florida made it the official state song in 1935, and later cleaned up the lyrics of its racial “insensitivities,” purged the references to “darkeys,” and tidied up its Uncle Remus dialect. The irony is that the Suwannee River basin is by far the most sparsely populated region of the state, and if and when Floridians pine for the Sunshine State, it is probably not the Suwannee River that they are thinking about. But it suits the nostalgic image of the Old Home Place that official songs and anthems are designed to evoke. It’s an example of the special kind of amnesia that official, legislated memory intends to induce.

Which is why, if you’re looking for a sentimental, nostalgic anthem for Florida, you pick a song written by a guy from Pennsylvania. Foster was born near Pittsburgh and never even set foot near the Suwannee. His identification with the river he made famous is entirely an accident of lyrical exigency: he chose the name “Swanee” when his brother found the river on a map, because the name it fit his song better than Yazoo or Pee Dee. If Foster had lived in 2018, he might well have googled “southern river” for a name that suited his songwriting needs.

In the 2000s, Florida seemed to realize belatedly that “Old Folks” did not necessarily speak for all the folks in Florida. A movement arose to replace Foster’s song with a newer, sunnier version: something that truly represented the self-image of Florida as a sun-soaked, pre-serpent Eden. So in 2007, the state sponsored a contest to find a new state song. The winner of the contest, “Florida (Where the Sawgrass Meets the Sky),” was written, like Foster’s, by a non-native. It was intended to replace “Old Folks,” but in a classic move of bureaucratic compromise, it was named the state’s new official “anthem” in 2008. In a classic Florida move, Foster’s song was granted the “emeritus” status and sent to the old folks’ home.

The new anthem is even more sentimental than Foster’s, if also more apropos of the idea of Florida:

Florida, land of flowers, land of light.

Florida, where our dreams can all take flight.

Whether youth’s vibrant morning or the twilight of years,

There are treasures for all who venture here in Florida.

Apart from the obligatory nod to the hordes of retirees in their “twilight of years” who flock to Florida every winter, this is not exactly groundbreaking songwriting. It’s certainly not Stephen Foster, and whoever wrote it is not likely to have a state park named for them. “Sawgrass” is a good example of what you get when state representatives commission official music: an entirely sanitized, unobjectionable vision of Florida that conforms to most people’s expectations of the place as a land of white sand beaches and dreams fulfilled, music as an arm of the Chamber of Commerce. Granted, state songs are not supposed to remind us that dreams take flight less frequently than they come crashing into the swamp to be eaten alive by alligators who do not give a shit about your dreams, or cruelly shift like the sands on the pristine white beach that Florida is supposed to be made out of.

To be fair, when Foster wrote “Old Folks,” he did not intend it to become a state song. Yes, Foster’s song is a racially patronizing, hopelessly idealized white vision of black longing. It is sentimental and nostalgic, but in a way that occludes the actual and inherited experience of the people the song is supposed to speak for. But at least the song evokes a real history, even if only a semblance of that history. It summons up a reality that official memory often seeks to dispel: the specter of human cruelty and malice that cannot be whitewashed away.

It is probably no coincidence that Henry Ford was a huge fan of Foster’s. In 1929 he opened the Henry Ford Museum and Greenfield Village in the heart of the Ford Motor Company’s main campus in Dearborn, Michigan. The museum provided a place for Ford to display the company’s history; the village allowed Ford to reconstruct his vision of American history. He purchased Thomas Edison’s lab, the Wright Brothers’ bike shop, Harvey Firestone’s family farm. Ford’s “mecca of Americana” was conceived as a monument to white industry and innovation: conspicuously absent from the collection were the achievements and creative products of Jews and African-Americans. In Ford’s vision of history, “American” meant “white. In 1916, blacks made up only 0.1% of the workforce at Ford (a number that would grow steadily as the Great Migration brought more and more African-Americans from the South to Detroit). But more tellingly, The Ford Motor Company’s own accounting distinguished “Jewish” and “Negro” employees from “American” ones. Ford’s American history came in any color, so long as it was white.

Foster was a perfect fit for Ford’s vision of America, so Ford purchased Foster’s birth home in Pennsylvania and relocated it to Greenfield Village, and dedicated it on Independence Day, 1935.

But Paul Robeson, on the other hand, did not jibe with Ford’s vision of America. Robeson recorded “Old Folks” in December 1930 as a B-side for His Master’s Voice. A titanic personality with outsized talent, Robeson was already on Du Bois’s radar in 1918, when Robeson was a senior All-American end for the Rutgers football team. In a short profile for The Crisis in March 1918, Du Bois highlighted Robeson’s achievements on the field, and added, almost as a footnote, that he “is a baritone soloist.” Football made Robeson famous, but music made him a legend. By the time he recorded “Old Folks at Home,” he was possibly the most popular and celebrated African-American singer in the world.

Robeson made his name on the stage and in film by initially playing characters that confirmed white stereotypes of happy negroes, and by performing minstrel songs that white audiences took for “perfect Negro songs.” After a sojourn in England and the Soviet Union, where he “felt for the first time like a full human being,” Robeson came to identify himself as an Afro-American, and when he returned to the United States he became actively involved in campaigning for civil rights. He soured on the old minstrel songs like “Old Folks” and stopped performing them, and put his prodigious, load-bearing voice behind a different vision of America. After the lynching of George and Mae Murray Dorsey, and Roger and Dorothy Malcom at Moore’s Ford in Georgia in July 1946, Robeson delivered a speech that September before 20,000 people in a rally in Madison Square Garden calling upon President Truman to act in response to lynchings that summer that had killed fifty-six African-Americans. Three months later, Truman established The President's Committee on Civil Rights, which ultimately led to the desegregation of the U.S. military in 1948.

During the same season in which Paul Robeson was recording “Old Folks at Home,” Ray Charles was being born 130 miles away from the Suwannee River in Albany, Georgia. Ray’s mother, Aretha, was from Albany, but lived in Greenville, Florida, in Madison County about an hour’s drive from the Suwannee River. Aretha travelled to Albany for Ray’s birth, and then returned to Greenville, where she raised him. Ray could literally cycle the streets of north Florida blind. He knew the area. He made his own, very Ray Charles adaptation of Foster’s song in 1957 for the album Yes Indeed!! With the Raelettes antiphonal responses evoking the music of the Black church, it’s jaunty and winsome, in every way Foster’s version is not, and would have made a decent choice for the Florida state song, but Georgia had already claimed Ray for his cover of “Georgia on My Mind,” first recorded by Hoagy Carmichael eight days before Charles was born.

The operative idea in every version of “Old Folks—including Gershwin’s derivative “Swanee”—is that the Suwannee River is really, really far, far away. It’s a placeholder for an unattainable object of longing, the Southern image of the end of the earth, about as remote from anywhere as it is possible to get, and definitely distant from the wild urbanity of New York City. But for Charles—unlike Foster—the Suwannee was home.

After he completely lost his vision at age seven, Ray was enrolled in the Florida School for the Deaf and the Blind in St. Augustine, established in 1885, the same year that Florida rewrote its 1868 “carpetbagger” Constitution. The new Constitution decreed that “White and colored children shall not be taught in the same school.” Originally the school was not segregated by race, but after opposition to integrated school teaching and a law initiated by William Nicholas Sheats in 1895, the state ruled that Blacks and Whites could not be taught in the same building together.

Even though many of the students could not see one another, the Black students were assigned to the Florida Institute for the Blind, Deaf and Dumb, Colored Department, where Ray was a student until 1945. The school was not desegregated until 1967.

Ray didn’t want to go to St. Augustine. So when he sang about

How my heart is going sad (so sad)

So sad and lonely

Because I’m so far (so far)

I’m far from my folks back home (from my folks back home)

he meant it, and felt it. His folks were way back in Greenville. Although the river itself was miles to the east, The “Swanee” was his home. He could sing about it with a depth of familiarity and experience that neither Stephen Foster nor Paul Robeson ever had.

Both Foster’s “Old Folks” and the newer “Sawgrass” are about the idea of Florida—and therefore the idea of America—an idea that has been sentimentalized and abstracted and endlessly reproduced. “Sawgrass” is all about finding what it is you think you seek. Foster’s original at least contains a trace of human longing, of desire for communion, of seeking and not finding. But it is a white man’s version of what a white man thinks a Black man wants, and the distance between desire and fulfillment remains determined entirely by white projection, by a white songwriter trying to give voice to Black longing. But in Ray Charles’ version, the distance between that longing is real and raspy—if somewhat disguised by the tune’s upbeat vibe. It’s an act of repossession, of retaking an idea that originated in the mind of a white writer and redeeming it with authentic experience. It’s also an example of how the story of American history ought to be told and voiced: again, hoarsely.

Listen to the “Foster’s Children” Playlist: