The Price of Not Punishing White Terrorism

by John Hayes

The study of history can reveal social forces and structural dynamics — the deep, often unseen currents that have such a powerful shaping influence on individual lives. And yet, too much emphasis on such forces can lead to a grim resignation, a belief that the choices in an individual life carry no weight, that the course of history has a rigid inevitability.

Though it is barely past, it’s safe to say that we live in the wake of a remarkable moment in our history: incited by the incumbent president, his most ardent supporters stormed the US Capitol, determined to violently stop Congress from verifying the outcome of the presidential election. Their electoral victory — indeed, their America — was about to be stolen from them, they were convinced, and in the face of such an existential threat, political terrorism was, for them, the highest form of patriotism.

Many commentators noted that it was not since the War of 1812 that the Capitol had been invaded. But if one is looking for parallels or precedents, it is Southern politics in Reconstruction that offers the most instructive lessons. Reconstruction was a remarkable moment of possibility in US history, when the trajectory of the future was unusually open. We know where the trajectory went, and it can be easy to concede that of course it had to be that way, that of course egalitarian change couldn’t happen so quickly. The life stories of Amos T. Akerman and Prince Rivers are a caution against such thinking. They faced political terrorism much more severe than our own, and they displayed remarkable strength of character in standing up to it. They believed in the democratic system, in the rule of law, and they had the audacity to hope that the future was not predetermined.

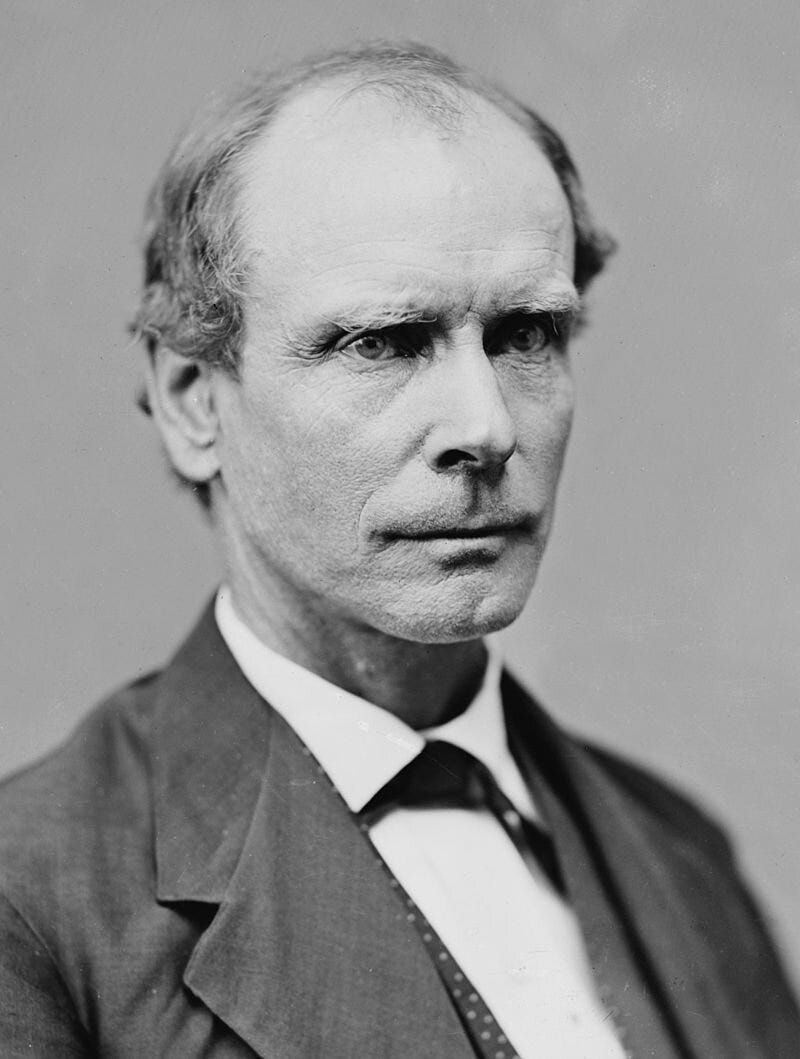

Akerman wasn’t a native Southerner. He was born in New Hampshire, but as a young man moved to Georgia and made it his home. Initially working as a teacher, he became a lawyer. Like many White men in his adopted state, he fought for the Confederacy. But in the tectonic drama of Civil War, something happened to him — he became radicalized for equality. As War ended he joined the Republican Party of Reconstruction, the Party that had ended slavery, the Party of equal civil rights for all and voting rights for all men. Working with Black men and with other White dissenters, Akerman helped to build the Republican Party in Georgia. He played a prominent role in Georgia’s 1867-68 constitutional convention, helping to craft an egalitarian document that boldly stated the (then-proposed) 14th Amendment’s vision of expansive civic equality.

President Grant’s choice of Akerman for Attorney General in June 1870 caught Akerman off guard. But once in office, Akerman wasted no time; he became a vigorous champion of equal justice. The Republican Party was still the majority party in most Southern states, but it was under violent attack from an anti-democratic terrorist organization, the Ku Klux Klan. Akerman mobilized the newly-created Department of Justice against the Klan. Terrorism had to face consequences, Akerman passionately believed. Paramilitary campaigns could not be allowed to subvert a political majority. The federal government had to show its seriousness in enforcing the epochal legislation of the 14th and 15th Amendments. His Department of Justice prosecuted hundreds of Klan leaders and put them in prison. As Klan terrorism had sought to make it dangerous to be a Republican in the South, Akerman sought to make it punishable to be a Klansman. By 1872, the resolute prosecution had borne real fruit. The Klan effectively ceased to exist as an organization. The elections that autumn were the fairest, most peaceful of the Reconstruction era. (A generation later, another Georgian would found a second Klan, in 1915 on top of Stone Mountain).

But Akerman’s commitment to justice went too far for some Republicans. When he began to investigate corporate corruption, the industrial capitalists in the Party called for his ouster, and Grant insisted on his resignation in December 1871. A year and a half later, when a White mob massacred Black citizens in Colfax, Louisiana, there was a paltry federal investigation that convicted three White men, but the Supreme Court overturned those convictions in its subsequent U.S. v. Cruikshank decision. Emboldened by the impunity, anti-Reconstruction Whites organized new terrorist groups — the White League, the White Liners, the Red Shirts — determined to resume the Klan’s paramilitary campaign of political subversion.

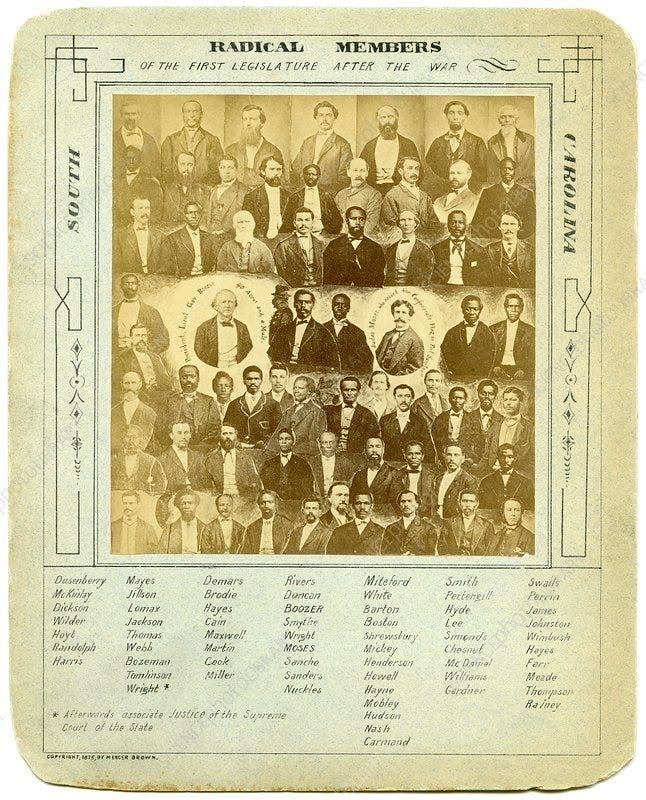

That campaign reached a grim climax a few days after July 4, 1876. In the predominantly Black town of Hamburg, South Carolina, a White mob overpowered a Black militia company, killing two members and then systematically executing four, including the town’s sheriff. Undaunted, Hamburg’s trial justice Prince Rivers launched an investigation into the massacre.

Born enslaved in Beaufort in the Lowcountry, Rivers came of age as a “house servant,” laboring as a coachman for the elite planter family who owned him. Against state law that criminalized slave literacy, Rivers taught himself to read and write. In the disruptions of Civil War, he seized a dramatic new possibility: he successfully escaped from enslavement and joined the Union Army, determined to fight for emancipation. Serving as sergeant in the 1st South Carolina Volunteers (later, the 33rd USCT), Rivers knew it was no ordinary moment. “This is our time,” he told a skeptical White journalist. Generations of enslaved people’s hopes had come to fruition in the cataclysmic drama of the Civil War.

After the War, Rivers became a leader in the Republican Party in South Carolina. He was a delegate to the 1868 state constitutional convention and was elected to the state legislature. His political work was of a piece with his military service: the ripe “time” of War could bear fruit, he hoped, in the expansive possibility of Reconstruction. By 1876, though, the promise of that new chapter had become palpably fragile. The national Republican Party was retreating from Reconstruction, and White terrorism was mobilizing with impunity. It was at great personal risk, then, that Rivers forged through with his investigation of the Hamburg massacre. White terrorism had to be punished. Black lives had to be valued. The rule of law had to be preserved. He issued warrants for the arrest of 87 White men, including the elite planters and mob leaders Matthew Butler and Benjamin Tillman.

Rivers’ courageous work propelled a US Senate investigation that winter. A Senate subcommittee collected extensive testimony, filling three large printed volumes. But the post-Akerman Department of Justice did nothing; no federal resources were put into prosecution, and nothing ultimately came of Rivers’ charges. And in the Compromise of 1877, resolving the disputed election of 1876, the national Republican Party ended its commitment to Reconstruction. With federal troops removed from the South Carolina state capitol, the Red Shirts occupied it, installing former Confederate general Wade Hampton as governor, sending Matthew Butler to the US Senate. In time, Benjamin Tillman would also be elected to the US Senate.

Rivers lived out his last years in forced deference, laboring again as a coachman. Having experienced enslavement, having fought in War and officiated in Reconstruction, he lived to witness, with anguish, a new Age of Reaction before his death in 1887. One wonders how different the trajectory might have been if the national Republicans had remained committed to protecting Black politics, to punishing White terrorism—if Rivers’ undaunted courage had the support of a determined federal advocate, if his fellow Southern Republican Amos Akerman had still been Attorney General in 1876, still been heading a Department of Justice that used federal power to punish political violence. As it was, Akerman returned to Georgia after his forced resignation and resumed humble work as a small-town lawyer. He died in 1880, a “known scalawag” who had “betrayed his race” in the pursuit of equal justice.