Last month I had the distinct privilege of speaking at The Atlanta History Center, a place that holds a very special position in my life. I mean both that venerable institution and the very specific ground it occupies in Atlanta, in the state, in the nation, in the cosmos. Read on (or watch) to understand why:

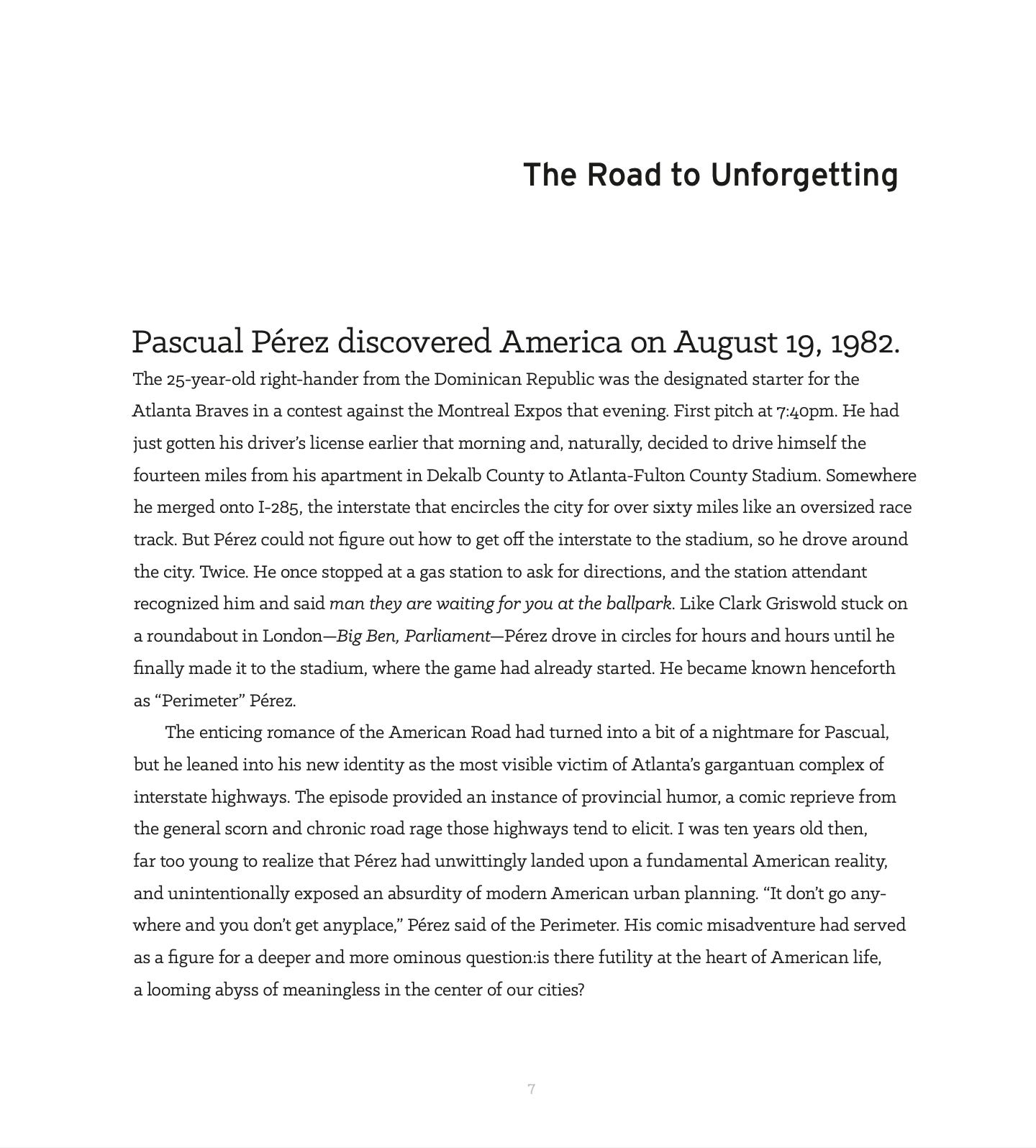

In his first novel, The Moviegoer, Walker Percy’s main character Binx Bolling recalls a childhood trip with his father to Chicago:

Not a single thing do I remember from the first trip but this: the sense of the place, the savor of the genie-soul of the place which every place has or else is not a place. I could have been wrong: it could have been nothing of the sort, not the memory of a place but the memory of being a child. But one step out into the brilliant March day and there it is as big as life, the genie-soul of the place which, wherever you go, you must meet and master first thing or be met and mastered. ... Nobody but a Southerner knows the wrenching rinsing sadness of the cities of the North. Knowing all about genie-souls and living in haunted places like Shiloh and the Wilderness and Vicksburg and Atlanta where the ghosts of heroes walk abroad by day and are more real than people, he knows a ghost when he sees one, and no sooner does he step off the train in New York or Chicago or San Francisco than he feels the genie-soul perched on his shoulder.

Percy thought that Atlanta was one of those “haunted places” like “Shiloh and the Wilderness and Vicksburg.” Why? For him, certainly the shadow of the Civil War still hung above the pavement, the ghosts and specters of the Old South roosting about in the pines and oaks and maples of Atlanta’s still- prodigious canopy.

To be fair, Percy’s novel was written in 1961, barely two decades distant from the premiere of Gone With the Wind at the Loews Grand Theater in downtown Atlanta, when, the Constitution reported, at least three Confederate veterans “in freshly pressed, be-medalled grey uniforms...sat alone, huddled in companionable silence, lost in thoughts brought back sharply by the raw scenes of a ravished Georgia countryside.”

Downtown Atlanta may have been haunted by such figures in the 1950s but by the early 1990s, downtown was haunted, it seemed, by precisely no one. Like the white folks, the specters and ghosts had up and left the city center.

The trees must have something to do with it. New York doesn’t have them, Chicago, for all its wind and space, doesn’t have them either. Los Angeles—not a chance. But there is something more, some other quality here that we may or may not share with some of those other great American cities, and I think it is something like the palpable sense in this town that history is something we have overcome, that progress will come to us if we just keep digging, grading, scraping, building, elevating. It’s a handsome myth—and music to the ears of the Chamber of Commerce—but it is a myth all the same. Atlanta sometimes seems to go out of its way to present itself as anyplace, USA: you can be anything here, anyone. And indeed Atlanta itself has sometimes branded itself as a generic placeholder for whatever you want to project on to it. I don’t want to dunk on Izzy any more than it ohas already been dunked on, but it was in so many ways a perfect mascot for Atlanta at a time when it was trying to prove itself to the world, without knowing exactly what it was trying to prove.

Atlanta has sometimes tried to run from, pave over, or otherwise escape its own history, or at least indefinitely postpone having to think about it. For example, on September 25th, 1869, Isaac Avery Wheeler, Editor of The Daily Constitution, called attention to “a communication suggesting the organization of an Atlanta Historical Society,” which suggestion it praise as “an admirable one, and should be acted on immediately.” It took us precisely 57 years to finally act on that suggestion, when this very institution was established in 1926.

That version of Atlanta was not especially good for you if you don’t want to be anyone. What if you want to be someone? Someone specific, someone rooted and without a place to claim and be claimed by.

I have tried for some time to understand what Percy meant by the genie-soul. Is it a person, like a druid or a fairy or wood-sprite? Is it something more vague and nebulous, like an atmosphere?

I think we can all agree that specific places generate specific feelings—related to our memories of the place, perhaps, or to some quality of unexpected newness that we don’t experience in the place we call home. But I believe that specific places generate specific thoughts, concepts: ideas that do not occur to you anywhere else. That is very much the case for me today. I find that as I stand on this spot I have a great deal to say, and little time to say it all.

I am here to talk to you about a book that is all about the mystery of place, the strange specificity of location, which is a little ironic because in 1949, my paternal grandparents built a house across the street from where we sit this afternoon, at 3204 Andrews Drive.

I learned to swim there. My parents posed for a photo in the shade of the backyard, days before my dad shipped out to Vietnam in 1966. My little league baseball teams of the late 70s and early 80s practiced on a field on the other side of the house, below the greenhouse where my grandfather grew eggplants including, I am sure, the first one I ever saw. It was in that house that I saw my first Georgia Football game on television, initiating a lifelong addiction from which there is no hope of recovery. I bet on my first Kentucky Derby race—and lost, although I still dispute the rulings of my elders, but mainly only to my therapist. All of that is baby-picture stuff to most of you, I understand, so how about this moment that many of you may remember. On July 18, 1996, the day before Opening Ceremonies of the Olympic Games, the Olympic torch passed this very spot, right in front of us here on West Paces Ferry. Not long after, The AJC told the story of the relay up to that point:

Then it was on to Buckhead for what may have been the wildest scene in the entire relay. When the torch reached the bar district after midnight, a young, sweaty multitude pressed in on the caravan and brought it to a complete stop. Former Mayor Sam Massell, the torchbearer on the segment, never broke a trot.

The AJC, God bless them, failed to mention that Mayor Massell wouldn’t have carried the torch had I not handed to him. OK fine, maybe that little detail would have added nothing, but it’s true—and the AJC accurately reported how crowds pressed in so tightly upon the relay that night—just out on the street up there—that it was impossible to get up any speed.

I didn’t know much of anything those days—I know even less now—and I didn’t really know who Sam Massell was, or what he meant to this city, nor what this city and this neighborhood owe to him. My education, while generally excellent, did not prioritize the particularity of place at all. The history of the city that gave birth to that school was never taught to us.

This was a serious deficiency—and an inattention to place led to other forms of egregious ignorance, such as the fact that nothing was ever made of the fact that Martin Luther King Jr was from here. No sense of local pride inspired attention to even that most obvious teaching moment.

I believe institutions no less than individuals have a moral responsibility to understand their own history, but in Atlanta ignorance of that history has often been treated as a kind of virtue. Which is why this institution is of such vital importance, and why I feel so honored to be connected to it today. That connection goes back a long way for me, to the repeated instances of descent down the driveway across the street, affording a view of this building, tucked deep into the woods, its distinctive skylights a kind of portent, an image of windows into this city’s history I would only begin to peer through years later. To think I would one day be under those skylights speaking to you, well it’s pretty incredible.

For all my talk about Atlanta this afternoon in the context of this new book, The Road to Unforgetting, it is possibly a little ironic that there is not a single photograph of Atlanta in it. In many ways, this is by design. There are no images of this city in the book, but there are lots of words about it. In some ways I have spent the last twenty-five years preparing to say something about my hometown, and I am grateful for the opportunity this book has afforded me of getting some of those thoughts on to paper.

The journey that started this whole project set out from Atlanta on 11 August 1997—a year after my historic and thrilling leg of the Torch Relay—and a matter of hours after a performance at Chastain Park by Johnny Cash. It would turn out to be his last show here, but it was for myself and John Hayes—my collaborator, co-pilot, and dear friend—the beginning of a journey whose end I could not yet see, and still cannot.

It started here because of what John and I were both becoming aware that the city was losing. Two important barbecue joints went under about that time, and not even their direct association with Dr. King, Andy Young, and others could save the historic venues from destruction. Forget all the self-righteous winging about how much damage General Sherman had done to Atlanta; we were doing a hell of a job of tearing it apart ourselves.

If you don’t mind I’d like to read a passage or two from the book to you all, since you know this city far better than I do myself.

And putting this place back together in my own mind and in my own story, I guess you could say, has often meant learning long after the fact, the weight of certain places where I may have played innocently or passed by with a cultivated insouciance typical of the kind of wealth and privilege that has characterized my upbringing. White privilege, as we now call it, really just meant the possibility of inhabiting spaces without having to be burdened by their histories.

One such example—a very happy one, in fact—is the baseball complex where I played Little League in the 1970s and 1980s. Once named Bagley Park, it was renamed in my time for a beloved little league umpire. Recently, thanks to the work of some people in this room, the Bagley name was restored to the park. What I certainly didn’t know then was that Bagley Park had once been the site of an African-American settlement named for one of its leading figures, William Bagley. Nor that the Black Atlantans who lived there were forced out to make way for whites, around the time Mayor Hartsfield proclaimed Atlanta “the city too busy to hate.” During or after baseball games there, some murmured that there was a burial ground over there, but I certainly never ventured over into that particular corner of local geography and history, which meant I never had to think about what any of that might have to do with me.

William Bagley’s name has been restored, and this is an important victory for the restoration of memory. And it is an especially salutary story, because it illustrates what is, for me at least, a fundamental point about this project. There are whole volumes of stories that we—I mean mainly white people of privilege and wealth—choose or have chosen to tell ourselves about the history of this place, indeed the history of our very selves—that softens the jagged edges of memory, soothes the addled conscience with tales of nobility and dignity, or, which is more commonly the case, omits them altogether, and assigns them to oblivion.

The price we pay for our willful amnesia about our past is self-deprivation: we voluntarily diminish our own humanity by choosing to forget stories that would make us more fully human, more completely ourselves. We replace hard stories with ennobling fables for all kinds of reasons, but the reality is that the real stories we forget are always—always—better than the ones we make up to replace them.

This city’s history is far more fascinating than we often realize, which is one reason among many why I am so grateful for this very institution and its vigorous growth. There are so many stories that we have yet to learn. The beautiful thing about this town, for me, is that what makes it so special is still to be discovered. When John and I started out in 1997, we struggled with that idea Atlanta has always had of itself as a city of the future. After 25 years of wandering around this region and encountering its ubiquitous genie-souls I came to realize that we have them here too. I came to appreciate that Atlanta is indeed a city of the future, and that future will lie in the rediscovery of our past.