[Dear Friends: by now you have probably heard the sobering news that Jimmy Carter has moved into home hospice care in Plains, which means that he will not be with us much longer. In profound gratitude for all that Jimmy has shown us about how to live and how to die, I want to share this excerpt from my forthcoming book, Prologue to the South, about their hometown of Plains. It is part of a larger section entitled “American Trilogy: Sumter County, USA,” an unusually dense convergence of quintessentially American stories.]

On a hot August night in south Georgia in 1898, Mary McGarrah and her son James Boone were brutally murdered with an axe. Within a day Hamp Hollis had been ratted out by his own wife and lynched for the crime, which he allegedly committed in response to being accused of stealing a slab of bacon. The story is rife with both improbable details and the over-the-top language characteristic of the subject matter at the time. “A more revolting, damnable crime was never committed by fiend incarnate,” read the local newspaper. All this took place in a town called Friendship.

There is little of Friendship left in Georgia now. What remains is simply the intersection of state roads 30 and 153, and the customarily disproportionate number of Baptist churches. Friendship is on the northwestern limit of Sumter County, a region of south Georgia that is rife with contradictions, where sin rides shotgun with Jesus. The county is home to three towns that are identical with contrary poles of American experience: in less than 500 square miles are sites associated with globally-recognized humanitarian organizations, a hammer-wielding nonagenarian ex-President of the United States, a wartime concentration camp, a baseball pariah, Christianity of almost every stripe. All of America’s favorite vices and virtues are condensed within the borders of Sumter County: pride, charity, lust, humility, courage, cowardice, violence, pacifism, racial equality and racist hatred. And baseball. Its county seat is, appropriately, named Americus, because Sumter County, Georgia, may be the most American county in the land.

* * *

Plains didn’t even make the 1940 WPA Guide to Georgia. It was a relatively young town by then, only incorporated in 1896, when, like so many towns in America, the laying of rail lines determined which intersections would be the loci of life. What is now Plains was originally called Plains of Dura, one of the three settlements that became one in the nineteenth century.

The prophet Daniel writes, “King Nebuchadnezzar made an image of gold, whose height was sixty cubits and its breadth six cubits. He set it up on the plain of Dura, in the province of Babylon.” It’s difficult to imagine a stranger namesake for this town. Plains is decidedly lacking in gold, and Sumter County has voted blue in the most recent elections. One of the poorest counties in the state, where two-thirds of African-American residents live below the poverty line, it belongs to the Second Congressional District, and has been represented by Sanford Bishop, a Democrat and African-American, since 1993. It has not been represented by a Republican since Reconstruction, and cannot realistically be called Trump Country. In many unexpected ways, Sumter County complicates the widely-shared perception of the South as mono-cultural or mono-political. But more than that: a little time here can help to loosen the hold of even the most possessive of American myths.

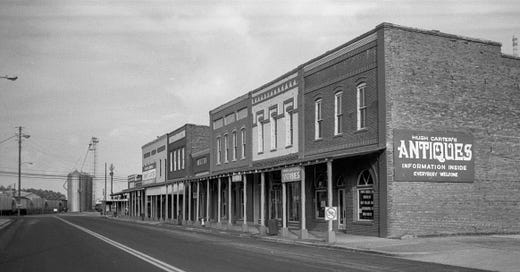

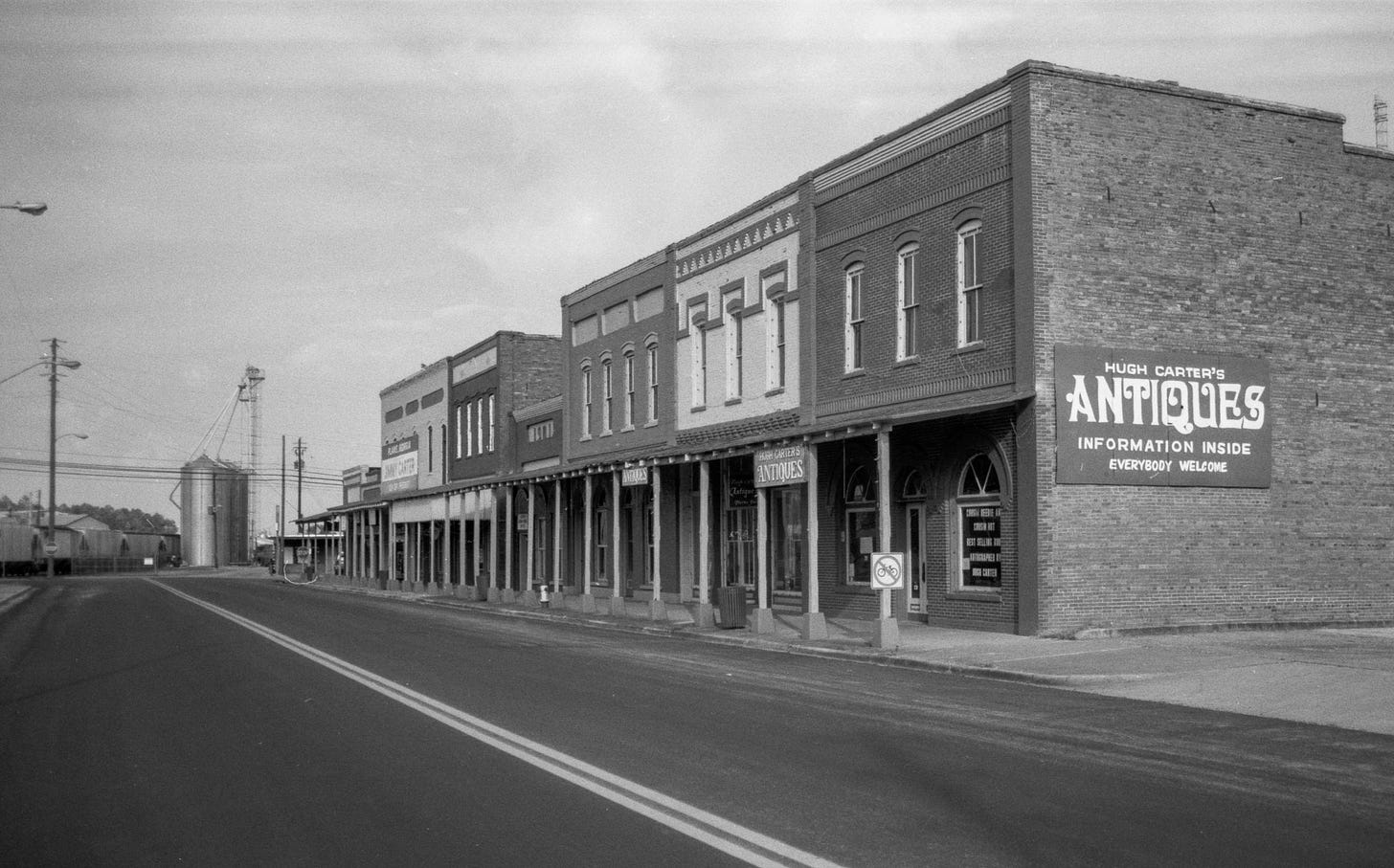

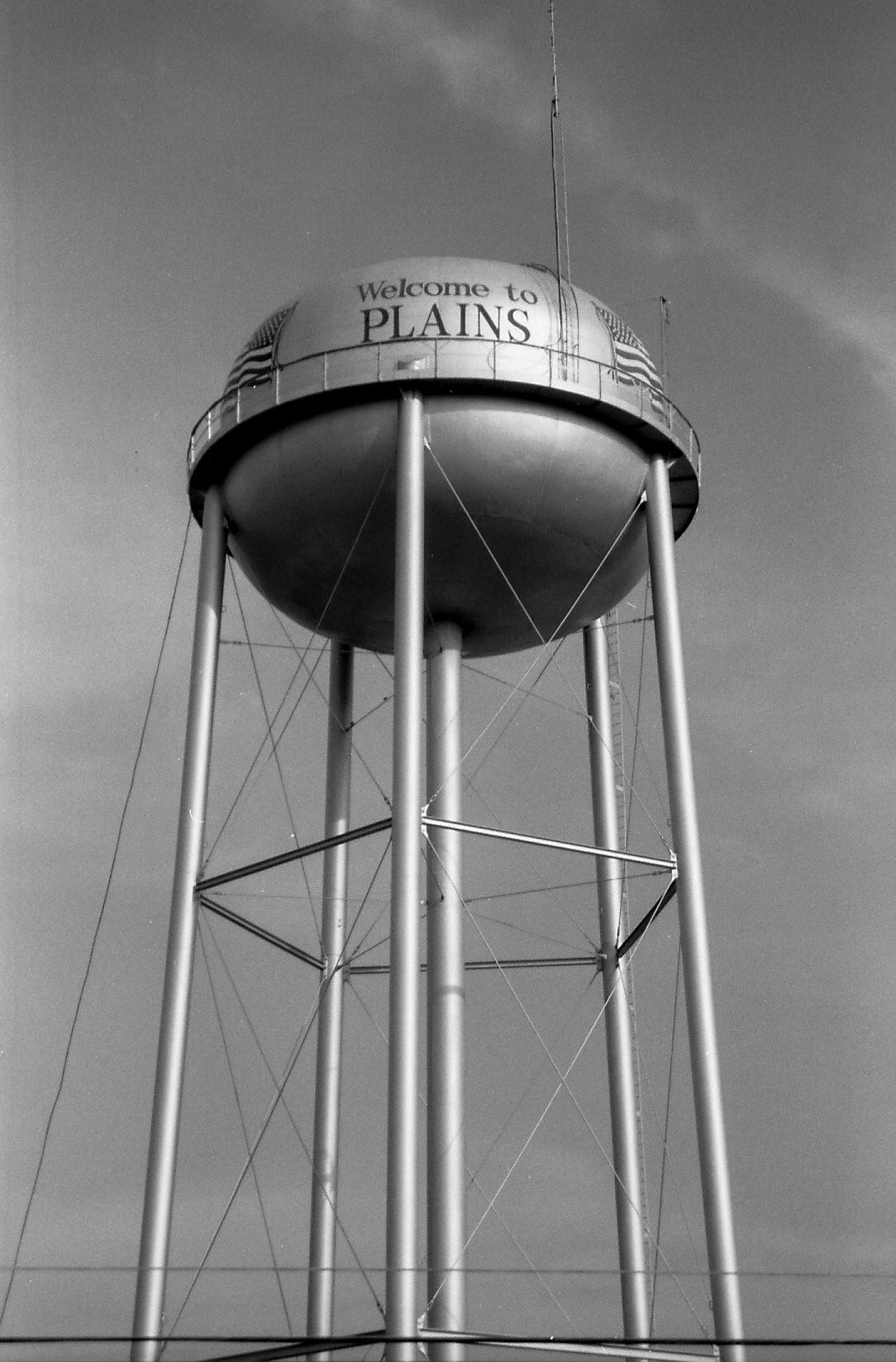

Plains is well-preserved, if not exactly lively. White wooden structures dot the area around the old depot. A fragment of a Main Street, not a full block long, two-storied brick structures fronted by a uniform rusted tin-roof veranda held up by painted four-bys. East into the bend on 280, silver-toned silos and elevators of grain mills, the silver water tower. All of it is post-apocalyptically quiet.

It’s also hot as hell. The center of Plains is the synapse of two parabolic curves — one for US 280 and the other for the railroad — which almost kiss each other at Bond Street, right next to Billy Carter’s Service Station. On my first visit to Plains in 1997, a marquis out front stood unsteadily on an arid patch of gravelly soil, amidst occasional pine seedlings and burnt-out grass. The light bulbs were all gone from the marquee, which delivered either a cryptic message or the remnants of one: I L LILIY. On the building, white an OPEN sign hung a-kilter from a nail next to the door. On the other side, a Pepsi machine, slightly incongruous for south Georgia.

I turned five years old a few weeks before Jimmy Carter was elected President in 1976. It was the bicentennial year, when myths of American innocence and nobility were probably at an all-time high. Not that I noticed much: in the years to come, I would hang on to the bicentennial quarters I’d come across, the ones with the colonial drummer on the tails-side. They weren’t worth any more than regular quarters, but I’d think twice before I stuck one into the coin slot of Asteroids or Pac-Man at the Timeout arcade at Lenox Square Mall. But if you absolutely had to use one of these special coins, you told yourself it just might get you a high score, or your initials onto the scoreboard. Maybe I implicitly believed somehow that the nobility of the tricorned figure and the cause whose drum he dutifully beat would redound to my benefit, however trivial.

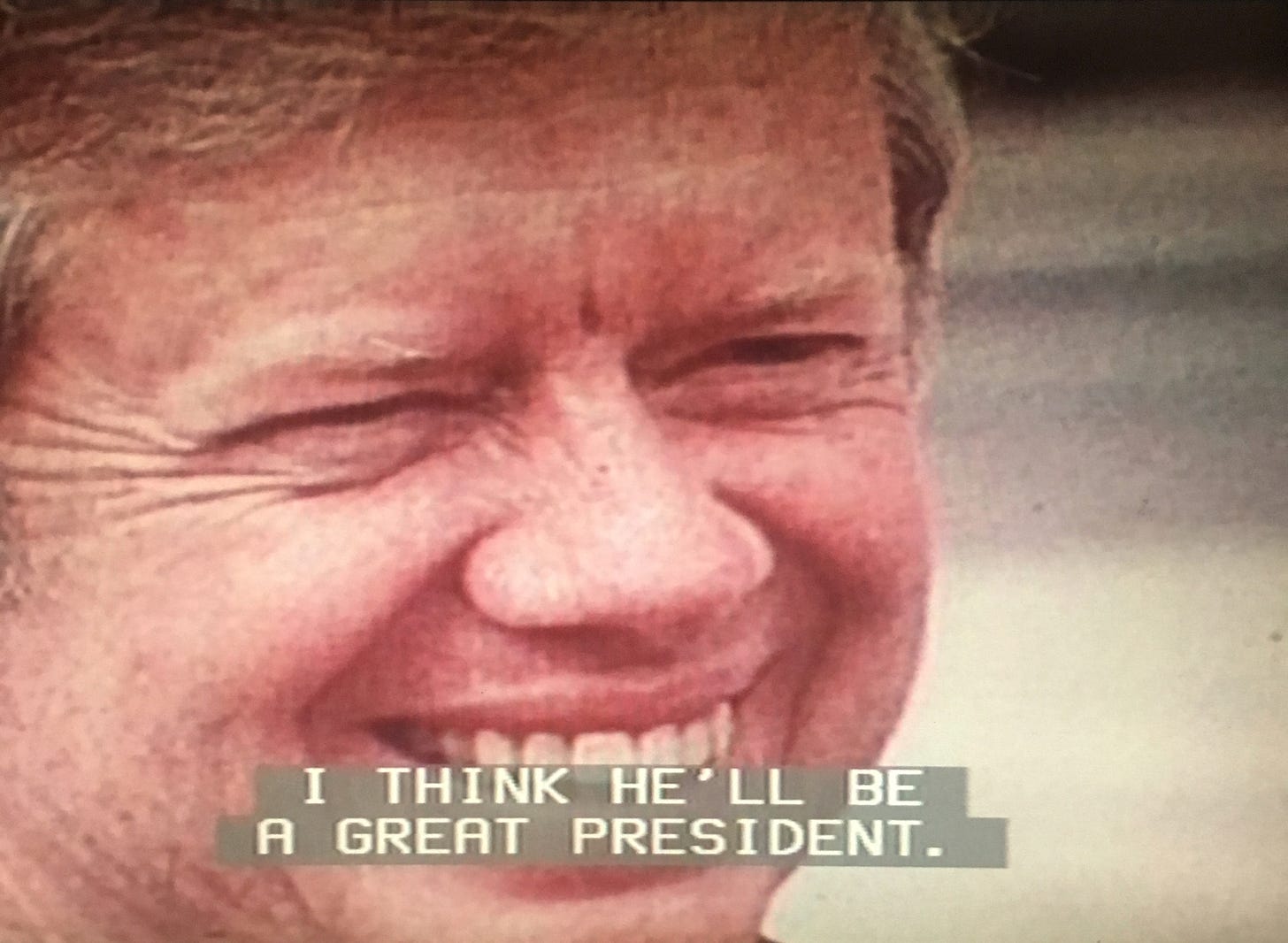

For most people who know about this sort of thing, there was not much worth remembering about Carter’s presidency. I remember almost nothing, but what I do is colored with the hot light of the Middle East: OPEC-induced lines of Buick sedans and Oldsmobiles at gas stations, a protracted hostage crisis, Anwar Sadat and Menachem Begin shaking hands in front of the White House, the Shah of Iran, whose name was emblazoned on a burlap bag of uneaten pistachios that sat in our kitchen counter for probably the whole of Carter’s presidency. But not much else. Presidential politics did not intrude into most little boys’ lives in 1977 the way it does into everyone’s life now whether we like it or not. If few people — including a lot of Georgians — were not all that happy with Carter in the late 70s, I wouldn’t have known it.

The white-clapboard railroad depot that served as the headquarters for Carter’s 1976 campaign is emblazoned with a sign saying as much. The depot faces the rail lines expectantly, as if waiting for Jimmy to roll in again someday. It’s a bit of a ruse. Jimmy still lives here.

In the window of one of the stores, a laser-printed leaf of white paper announces the dates Jimmy will be teaching Sunday School at the unassuming Baptist Church up the road.

Inside is a fittingly unvarnished, raw timber museum to Carter’s Presidential Campaign. In the foyer is a case of campaign buttons, including one announcing, “JIMMY CARTER LUSTS…FOR ME!” It’s a reference to the famous interview Carter did with Playboy Magazine in 1976, in which he confessed, “I’ve looked on a lot of women with lust. I’ve committed adultery in my heart many times.” Which, naturally, initiated a bona fide shitstorm in Georgia and Texas and elsewhere where much of the electorate was shocked to learn that Playboy printed interviews with words.

Carter was not universally rewarded — much less absolved — for his confession, especially among those who thought then that religion was a private matter between you and God and not you and the readership of Playboy. It seems quaint that a President should have once been pilloried for an unexpected act of honest introspection, especially on our 2018 visit, during the regime of a President who has proud and unapologetic admission of grabbing women anywhere he likes, who likens his own misfortunes to a “lynching,” has not only not been condemned by the evangelical establishment but celebrated as God’s gift to America.

In 1975, he was “Jimmy Who?” But now he has the universal appeal of a rock-star, but one whose life has been given over to people who haven’t fared as well as he has. Nowadays people generally don’t seem so insistent on keeping religion a private matter, as long as it agrees with their ideas of what a religion is supposed to be for. In ‘76, Carter’s frankness about his faith did not play well everywhere; today he is a model of what a public, lived Christianity can look like. Jimmy seems to embody an idea I once heard the novelist Marilynne Robinson put into words: “I am a Christian, but I am not angry at anybody.” The Carters have deep roots in the soil of Sumter County — both its contradictions and its best aspirations — and from the area’s peculiar culture of lives in service to others. They could easily be cooling their heels in some Florida high-rise, but they haven’t chosen that life.

* * *

Friendship is not entirely absent from Sumter County now. Even now there are images of alternative lives, of people determined to make America otherwise, crack-ups that lead the other way from despair. One is Jimmy Carter, nearly a century old, his right eye bruised and stitched up after a fall, tapping nails into someone else’s home on one day, on Sunday sitting in a packed sanctuary at the Baptist church teaching about kindness to the friendless. A contradiction, perhaps, but a hopeful one: wounded and frail, bloodied and bandaged, but a servant of others, a living nevertheless.

In 2018, twenty-one years after my first visit here, we drive past the Carter compound en route to the screen-porched Sears-Roebuck house where he spent his youth. We pass Jimmy and Rosalynn walking along the four-lane to dinner at the retirement home next door. It is 5:30. Rosalynn is 90, Jimmy is 93, same as the temperature. They could have had food delivered. They could share the parasols the casual security detail behind them is using, or ride with the guys in the black Tahoe with the A/C on. But soberly, determinedly, they walk.

Oh, my! Reading your words are akin to feasting on the most delicious, bountiful gourmet meal!

I am so proud of you for bringing forth truth, reality, history and goodness through your God-given writing! Love, Mom

Thank you! It’s long been a comfort to me that the Carters live “just down the road” from me; I’m in Columbus.