KKKU

In 1920, the Klan was floundering.

Its high-profile revival on top of Stone Mountain in 1915 was timed to coincide with a wave of enthusiasm for D. W. Griffith’s notorious Klan-glorifying blockbuster, The Birth of a Nation, but five years later, membership had plateaued.

The founder of the Atlanta-based Klan 2.0, “Colonel” William J. Simmons, had poured so much of his natively grandiose soul into his “high-class mystic, social, patriotic, benevolent association” that he had come to identify his own personhood with the organization itself. “I alone am responsible for the reorganization of the Ku Klux Klan,” he wrote in 1923.

While Simmons would claim re-organizing as a kind of divine gift, being organized was not in his skill-set. Despite an irrepressible enthusiasm and congenital hucksterism, he was unable to get the group over the hump of a few thousand members in its first five years. What Simmons needed was a PR team. He found it in Edward Young Clarke and Mary Elizabeth Tyler, the owners of The Southern Publicity Association whose résumé included The Salvation Army and the Anti-Saloon League. But by 1920, Clarke and Tyler needed money, and Simmons needed members. Together the new management came up with a membership program whereby every new member paid to the Klan an initiation fee (called a “klecktoken”) of $10.00, $2.50 of which went to Clarke and Tyler each. The system was poorly thought out, and the lack of regulations led field recruiters to pad their numbers and pocket the fees from fake, non-existent recruits. But it was also designed to make the Klan grow with breakneck speed and to make Clarke, Tyler, and Simmons fabulously wealthy.

To sell itself nationally, the Klan adapted its marketing strategy to suit local prejudices. In California, it appealed to anti-immigrant sentiment. In eastern Tennessee, it played on local suspicion of Greeks. By the time the Klan reached its peak in the middle of the 1920s, it could claim as many as four million members nationwide. Its main message: “Americanism,” a fruit of the WWI/Wilson-era fervor for national unity and conciliation in the long shadow of the divisions of the Civil War. By this time, white Americans had become averse to “sectionalism” and executed a compact with one another in both North and South on the explicit agreement that while the Civil War was devastating, and slavery abolished, it was still a white man’s country.

The new scheme Clarke and Tyler put into place was so wildly successful that Klan membership skyrocketed nationally, reaching as high as four million members at its peak. The Klan purchased a not-at-all subtle Greek Revival mansion on Peachtree Road as its “Imperial Palace.” It confidently offered its assistance as a parapolice organization to local law enforcement around the country for assistance in maintaining “law and order.” Tyler built a plush new home in Buckhead. The Klan began to show its political muscle in local elections. Then it got cocky.

Simmons turned his attention to—of all things—higher education. In August 1921, the Knights of the Ku Klux Klan took ownership of Lanier University in the Morningside-Lenox Park neighborhood of Atlanta. Simmons took over as President, and quickly transformed the Baptist college into an organ of the Klan designed to teach “pure Americanism.” The Klan purchased 45 more acres adjacent to Lanier and planned a new building called “The Hall of the Invisibles,” which would be singularly dedicated to “the teaching of Klancraft and the ideals and principles of Ku Kluxism,” but was “to be operated separately from Lanier University.” Simmons stacked the executive staff of Lanier with Klan brass with recognizable Ku-Kluxist bona fides: for the secretary and business manager of the new school, Simmons hired “General” Nathan Bedford Forrest II. The grandson of the original Nathan B. Forrest—first Grand Wizard of the first Klan, founded in Pulaski, Tennessee, in 1866—the new secretary of Lanier University was not an actual general but was the Grand Dragon of the Klan and Commander in Chief of the Sons of Confederate Veterans.

Lanier hadn’t been in Klan possession for five months before Simmons got the wandering eye. It may have been encouraged by the fact that Lanier students and faculty had gone on strike for the University’s failure to honor its promises to them, or the fact that faculty grievances were small potatoes to a man who was making more money than he knew what to do with.

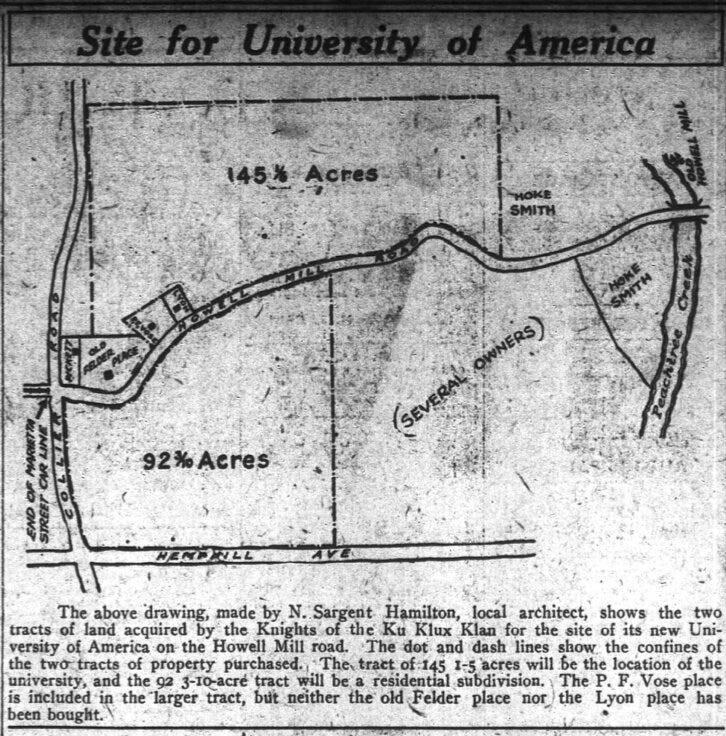

In late 1921, the Klan’s factory in Buckhead was turning out 600 robes a day and selling them for $6.50 a piece ($8.00 for horse-robes). Combined with an incoming flood of $10 initiation fees, the Klan was rolling in it. In 1922, riding high on swelling coffers and wide public confidence, William Simmons’ Klan had its eyes on bigger fish. As the shine wore off the Lanier University property, Simmons had designs on two tracts of land totaling 237 acres in Buckhead near where Confederate troops had fought a losing battle against Union forces at the Battle of Peachtree Creek on July 20, 1864. Losses were heavy—as many as 4750 combined casualties—but the land was fertile with Lost Cause symbolism for Simmons’ dream project. In early February 1922, the Knights of the Ku Klux Klan paid $3,000 of the $60,000 down payment for the property that would become “the seat of Ku Klux Klan Kultur.” In July 1922, Clarke announced plans to abandon Lanier University and transfer all its operations to a new university that did not even exist yet.

At the same time, legal troubles were already brewing. An insurgent movement against Simmons, Clarke, and Tyler sued the Klan’s “Big Three” and sought to have the organization—including Lanier University—placed in receivership. Plaintiff Harry B. Terrell and 400 other disgruntled Klansmen claimed Simmons’ Klan was bankrupt, and during the trial the Fulton County Superior Court demanded documents from the Klan leaders. Eventually the case was dismissed by Judge George Lester Bell, but it was already apparent that in this “fraternal” organization, “there was,” as Bell put it, “not much brotherly love lost in the family.”

The new tract in Buckhead provided Simmons and Forrest the opportunity to integrate the Ku Kluxism into their overall pedagogical program in a way they had not been able to at Lanier. The planned “University of America” would be a Klan institution intended to teach “Americanism” and “the teachings of Christ.” It was emblematic of the Klan in the 1920’s, which was an enormously popular organization with millions of adherents not only in the South but all over the country. Built on resentment of immigrants, Jews, Catholics, and Blacks, it attracted members from Detroit, Oregon, and Indiana in droves.

The new university would be funded on a subscription plan of “One million dollars to Americanize the youth of America,” as fundraising coordinator W. J. Mahoney put it. The campaign solicited 1,000 subscriptions of $1,000 each. Its earliest contributions came from Denver and New York. Eight klans in Chicago pledged $100,000.

Plans were aggressively ambitious: the campus of Lanier University would be retained and become a branch of The University of America, a lecturers’ bureau would be established to furnish a hungry listening public with speakers on Americanism and white Protestant Christianity, and Mahoney confidently promised it would be “the foremost university in the United States.”

The educational mission of The University of America was a classically early-twentieth century hybrid of American nationalism and a version of Protestant Christianity (“after the outstanding Protestant of all times, the Lord Jesus Christ”) especially haunted by the specter of communism. Forrest promised:

We will teach that this is a white man’s country, so designed by those who laid its foundations and that it must be so maintained by those to whom it has come as a precious heritage, in all that is entailed as privilege and as responsibility…We will teach the whole American doctrine in contrast with the doctrines of other countries and races, other kinds and creeds, and in such a way as to convince the student that it is better to be a genuine white Protestant American citizen than to be anything or anybody else anywhere on all the earth.

At the same time, Simmons began to lose his grip on the management of the rapidly-expanding and rapidly-imploding Klan. He handed leadership over to Clarke, and established a national Klan organization with jurisdiction over local groups. On July 11, 1922, Simmons proclaimed the establishment of the new Imperial Klan on the grounds of his future university where, “with deep solemnity, the charter members of the Imperial Klan knelt about the Fiery Cross and the Flag of their country.”

“The nation is calling us,” Simmons declared, “and we are answering the call, and a faint cry is being heard which undoubtedly will later become a loud clamor from the white men of the world to take their banner and fling it to the breeze and lead in the fight for world-wide supremacy of the white race and for the Protestant evangelization of the world.”

“Their banner” was not the Confederate battle flag, but Old Glory. When Simmons’ Klan began convening in 1915, it did not use the Confederate battle flag in its rallies. It didn’t need to. The American flag itself—and its associations with “Americanism” and the racialized social contract—already did the imaginative and symbolic racial work that the Rebel Flag had earlier done, and would do again. So when Simmons & Co. sold the idea of “Americanism” around the country, it appealed to nativist tendencies everywhere, and to people who would not question the a priori nature of white supremacy as constitutive of American identity.

In the 1920s, white supremacy was not a niche position, and The Knights of the Ku Klux Klan were hardly an outlier to America’s bulging roster of fraternal organizations. In March 1922, the state of Georgia issued a charter to “The Great American” fraternity, a composite group that gathered into one organization the Masons, the Guardians of Liberty, the Daughters of America, and the KKK. Nor was it a pariah to Atlanta society: it established its headquarters on Peachtree Road in Buckhead, and its baseball team played in public games against squads from local churches. At its 1922 initiation ceremony, thousands of attendees watched as new recruits were gathered around a burning cross in the center of a circle illuminated by car headlights in Piedmont Park. Carl Hutcheson, member of the school board, praised the Klan as “potential saviors of our republic.”

But the would-be American messiahs were finding their Palace increasingly divided against itself. Despite the enormous rise of the Klan thanks to the publicity and recruiting strategies of Clarke and Tyler, rifts internal to the organization began to appear in 1921. Rival factions—one including Simmons, Clarke, and Tyler, and another composed of other aligned with Hiram W. Evans—duked it out in court to determine the fate of the Klan. Evans would eventually wrest control of the Klan from the Simmons faction, which had begun to unravel. In the midst of this internecine strife, facing declining health and a history of impropriety, Tyler resigned her post as publicist for the Klan, and was eventually replaced by a Texas newspaperman, Philip E. Fox.

In California, Grand Goblin of the Pacific Domain William S. Coburn vowed to “expose those who are breaking laws and hiding behind the Ku Klux Klan.” In April, Coburn was tangled up in inquests into the Klan’s alleged involvement in a night raid on a suspected bootlegger in Inglewood, California, but denied his or any official Klan involvement. The attention of the authorities and potential exposure of Klan secrets was not welcomed by Fox or Simmons, nor were the indictments of forty-three Klan members in California, including Coburn. His arrest on June 19 was headline news in the Los Angeles Express.

By 1923, the Klan’s publicist, Philip E. Fox, had become attached to the Evans faction and convinced of a conspiracy against him by Simmons and his associates, including Coburn. Fox feared Coburn’s prying would reveal Fox’s illicit affair with a married woman, among other things. In November 1923, wearing a heavy overcoat, Fox walked into Coburn’s office in Atlanta and shot him five times.

And external pressure on the Klan was increasing, too. Simmons and Klan leadership in Atlanta spent much of 1922 defending the Klan from accusations of involvement in acts of intimidation and physical assault, bombings and church burnings, and murder. One local lawyer attempted to establish an anti-Klan organization called “The Knights of the Visible Empire,” and a Federal judge in Texas called the Klan “a smooth system of chloroforming the government under the plea of 100 percent Americanism.”

But much of the opposition to the Klan was not for its “Americanist” white supremacy: many objected more to the method than the message. “There are many honest people who are in it,” said Georgia Governor Thomas Hardwick, “and who went into it with the highest and most patriotic motives for its creed and principles are patriotic and unassailable.” But, Hardwick argued, “we have no room for invisible government in this state.” For Hardwick and many other public officials, the Klan’s problem was its secrecy, not its principles. The Klan took Hardwick’s message to heart: Imperial Wizard pro tem Edward Clarke ordered the Klan to unmask, but ultimately Hardwick’s slap on the wrist of the Klan cost him: in the 1922 gubernatorial election, he lost to Clifford Walker, an Klansman. By then masks and hoods were no longer especially necessary. Insiders claimed that over half the Georgia legislature belonged to the KKK.

The Klan under Simmons was adept at getting people on board, but horrible at executing its lofty plans. The university failed to raise the $1,000,000 in donations to fund the new university, and by 1923 all talk of Klan U. had virtually disappeared from Atlanta’s newspapers.

Infighting and grift—that led to a high-profile murder of one senior Klan official by another—signaled the beginning of the end of the Klan and its University in Atlanta. Evans sold Simmons’ Imperial Palace, and relocated Klan headquarters to Washington, DC, where he exerted his organization’s political power to influence elections all over the country, and organized a march in 1925 down Pennsylvania Avenue featuring 30,000 hooded, but unmasked, Klansmen. By then the Klan had long given up on being a secret society: it was now part of the mainstream.

But history sometimes winks knowingly, if you look it in the eye. The Imperial Palace ultimately became the site of the Cathedral of the Roman Catholic Diocese of Atlanta, and in 1946 a portion of the Lanier University property was taken over by a Jewish synagogue. At the corner of where the planned University of America was to have been, there is a Publix.

The Klan did not, of course, produce “the foremost university in the United States.” It didn’t produce a university at all, but through its own chronic venality and fraudulence, it did manage to successfully sabotage the two it attempted to operate. Today there is no visible sign of the Klan’s abortive attempt to “Americanize” the youth, but its white supremacist, “America First” sensibility is very much alive, if you only look everywhere.