Next Door is Closer than You Remember

The week leading up to Independence Day 1913 was a turning point in American self-understanding and selective memory: while tens of thousands of Union and Confederate veterans gathered in Gettysburg, Pennsylvania, for a “festival of national reconciliation,” over 4,000 people attended the opening of the The Hotel Ansley on the corner of Forsyth and James Streets in Atlanta to celebrate the opening of “one of the most attractive and most modern hotels in America.” It was supposed to be a bright new morning for the nation and for the “new South:” a forward-looking consolidation of national and regional identity through public memorials and private galas. The Gettysburg reunion was a classically American attempt at national healing through a conciliatory barbecue; the Atlanta opening an equally characteristic act of black-tied atonement through commercial progress. Both events shared something else in common: those whom they left out of the new national consensus. No black Union veterans were invited to the Gettysburg event. In Atlanta, despite proclaiming itself in 1913 open to “every Southerner,” and promising to be “the home of all Georgians visiting Atlanta,” the doors of the Ansley would be closed to African-Americans for another fifty years.

Bought in 1952 by the Dinkler Hotel chain, The Ansley was renamed the Dinkler Plaza Hotel, and for the next twenty years it would never be very far from controversy and/or tragic drama. In January 1961, Carling Dinkler, president of the Dinkler company, threw himself from the window of his suite on the twelfth floor of his hotel. A hotel spokesperson attributed the tragic “fall” to health-related depression following abdominal surgery the previous year, a position maintained by Dinkler’s inner circle even after the county coroner ruled his death a suicide. It was a macabre case of déjà vu: Carling’s father, Louis, had also taken his own life in one of his Atlanta properties, in the basement of the Piedmont Hotel in 1928.

The hotel chain passed to Carling Dinkler, Jr., who, less than a month after his father’s death, sold the Dinkler Hotel company to Transcontinental Investment Corporation for $14 million in a deal that was in the works before his father died. Carling Jr. stayed on as president, but relocated to Miami not long after handing over the chain’s daily operations. If Junior appeared in the newspapers in the 1960s, it wasn’t usually in the business section. The Dinklers were more at home in the society pages, palling around with the likes of Mrs. Clark Gable, or in the sports section, which occasionally reported Carling Jr.’s latest golf scores.

But back in Atlanta, the Dinkler Hotel still seemed to attract tragedy.

In August 1962, Lucile Robison of Knoxville met Henry Solomon Meador of Meridian on a passenger train in Louisiana. The two started dating, and soon moved in together. But by the spring, the relationship had started to go south. Robison could see no way out, and when she told Meador she was leaving him, he did not take the news well. According to her version of what happened, he threatened her with a pistol. As she was packing her bags, he went for his gun. But Robison got to it first, pushed him onto the bed and shot him. “The gun went off several times,” she told police. At least five .25 caliber rounds ended up in Henry Meador’s head.

Robison fled New Orleans and ended up in the Dinkler Plaza Hotel in Atlanta, where she shot herself twice in the chest.

She somehow survived the attempted suicide, was arrested and extradited to New Orleans, where she was to be tried for murder. At her arrest she claimed to have been distraught, telling police that “I felt so remorseful about what I had done I didn’t feel like I could face life anymore was the reason I shot myself.” But the story became even more confusing when, in the New Orleans apartment she had shared with Meador, notes were found that seemed, improbably, to suggest a suicide pact.

Like most, if not all, white-owned hotels in Atlanta at the time, the Dinkler Plaza remained officially white-only until the mid-1960s. And across the southeast, the Dinkler Hotels played host to segregationists at auspicious occasions. In December 1951, a detective found Eugene “Bull” Connor in room 706 of the Dinkler-Tutwiler Hotel in Birmingham, in a compromising position with his secretary. The detective promised to put both of them in jail for “joint occupancy of a hotel room” between an unmarried male and female, a law Connor himself had pushed for. But this being Bull Connor, no charges were ever filed.

In 1962, the Dinkler Plaza in Atlanta refused to let a room to the diplomat and political scientist Ralph Bunche, who in 1950 became the first African-American to be awarded the Nobel Peace Prize. In June 1963 the Dinkler Plaza, along with about a dozen other hotels in Atlanta, agreed to a limited desegregation plan, but that did not stop the hotel from hosting Governor George Wallace to addressed a Citizens’ Council meeting in one of their ballrooms. Hundreds of African-American students protested outside while indoors Wallace bitched about commies and John F. Kennedy, and his host, former Governor Marvin Griffin, poked not at all subtle fun at Atlanta Mayor Ivan Allen, Jr., who could not attend because he was in Africa. On January 11, 1965, Bull Connor was back in the spotlight at the Dinkler-Tutwiler in Birmingham, but for very different type of affair. This time he was the main attraction at a $10-a-head dinner to swear him in as the new president of the Alabama Public Service Commission.

When the Dinkler was given a second chance to host an African-American Nobel Peace Prize winner, they approached it differently. In 1964 the hotel planned to host a welcome-home banquet for Atlanta native Martin Luther King, Jr., upon his return from being awarded the Nobel in Oslo. At first, few of Atlanta’s white business leaders RSVP’ed that they would attend. It was looking like it would be a huge embarrassment for the Dinkler and for the self-described “city too busy to hate.” It was also shaping up to be an embarrassment for J. Paul Austin, the chairman of Coca-Cola. He told a hastily-convened meeting of white business leaders at the Commerce Club that “The Coca-Cola Company does not need Atlanta. You all need to decide whether Atlanta needs the Coca-Cola Company.” Two hours later, the event was sold-out.

![Martin Luther King, Jr. receiving an award from Rabbi Jacob Rothschild in recognition of his 1964 Nobel Peace Price at a dinner in his honor at the Dinkler Plaza Hotel on 27 January 1965. [Photograph courtesy of the Atlanta History Center.] Martin Luther King, Jr. receiving an award from Rabbi Jacob Rothschild in recognition of his 1964 Nobel Peace Price at a dinner in his honor at the Dinkler Plaza Hotel on 27 January 1965. [Photograph courtesy of the Atlanta History Center.]](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/w_1456,c_limit,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fbucketeer-e05bbc84-baa3-437e-9518-adb32be77984.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2F188d176c-c775-40ad-ac6e-4e7743dac3a9_498x400.jpeg)

It’s unclear where the Dinklers were on the night of the event. For years Junior and his wife Connie had been double-dipping in Atlanta and Miami, until they permanently relocated to Biscayne Bay in the early 1960s. By the time of the dinner in honor of King in January 1964, Connie Dinkler was deep into her own social improvement project for Miami.

Connie Dinkler was the sort of person who could form sentences like this: “The most difficult people in the world are yacht captains, French chefs and English nannies.” Her vision was miles away from the one being begrudgingly honored by Atlanta’s white business elites that winter. “President Johnson is taking care of the poor,” she said in 1965. “Well, I’m going to take care of the rich.”

In 1972, the Dinkler Plaza Hotel was being gutted and stripped down in Atlanta as the twenty-seven story Palm Bay Towers was going up at the Dinklers’ Palm Bay Club on Biscayne Bay. The old hotel in Atlanta where many of the transactions between white and black Atlanta were conducted had come to a glitterless end. In late August 1972 the hotel was selling off carpets, sinks, and tubs for five dollars a piece, china at twelve pieces to the dollar, banisters, ceiling tiles, strip lighting.

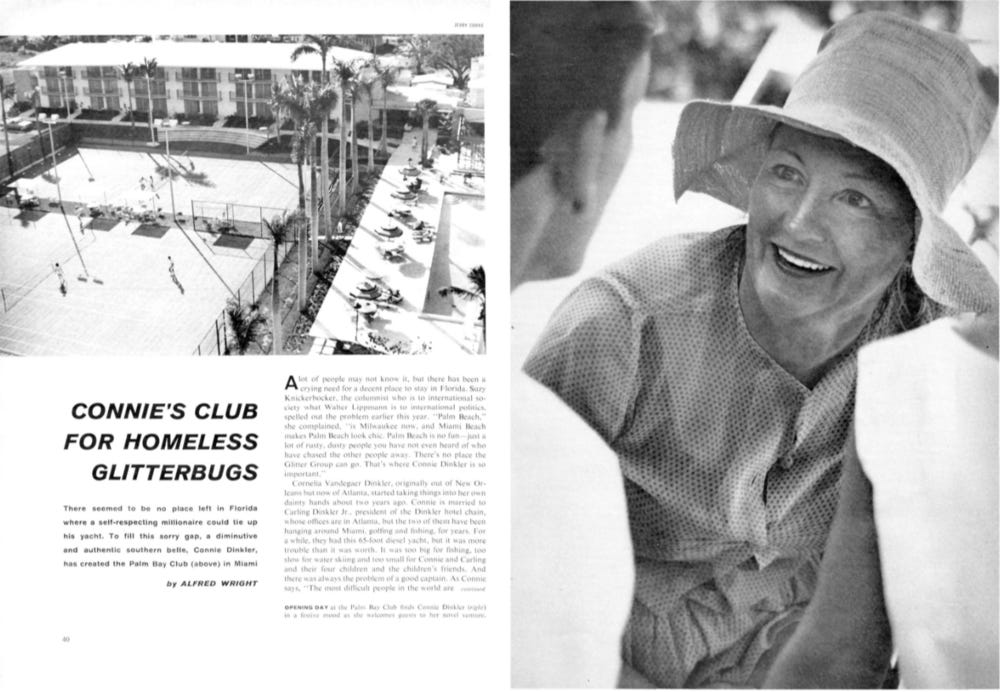

In 1973 the Dinkler Plaza was razed while across the street, the original public library faced a similar fate. Built in 1900, by the 1970s it had become cramped and musty, its tile floor splotched with cigarette burns, most of its books hidden away in closed stacks. The old library had been funded by a $125,000 gift from Andrew Carnegie, but funding a new one to replace it proved more difficult and more costly. By 1975 a new library had become a regular topic on the editorial pages of the Atlanta Constitution. At a December 9th, 1975 bond referendum, Atlanta voters narrowly approved almost $19 million for a new library to be built according to a 1971 design by the celebrated modernist architect, Marcel Breuer, who had also designed the very similar Whitney Museum in New York (now the Met Breuer). The library was finally completed in 1980, a year before Breuer’s death.

![Marcel Breuer’s 1980 brutalist masterpiece, the Atlanta Central Library. In the background, the Peachtree Plaza, then the tallest hotel in the world. [Photograph courtesy of the Smithsonian’s Archives of American Art] Marcel Breuer’s 1980 brutalist masterpiece, the Atlanta Central Library. In the background, the Peachtree Plaza, then the tallest hotel in the world. [Photograph courtesy of the Smithsonian’s Archives of American Art]](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/w_1456,c_limit,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fbucketeer-e05bbc84-baa3-437e-9518-adb32be77984.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2F5b65cd48-23f4-4b32-8760-e4a5ac68b03b_1000x797.jpeg)

But getting there was a classic case of Atlanta politics. Maynard Jackson was almost two years into his first term as Atlanta’s first African-American mayor. He had pressed hard for the four-part bond issue, which was to include improvements to roads and sewers, parks and zoos. The library was the only part of the referendum that passed, and only just. The vote fell along largely racial lines. White voters, especially in Buckhead and other affluent suburbs, did not support the tax increases necessary to fund those infrastructure projects. According to Jim Merriner’s day-after analysis in the Constitution, Jackson’s plan had been to get out the black vote in such high numbers so as to counteract white opposition to the bond issue. They did turn out, and approved the bond package by over 65 percent. But white voters turned out in higher numbers than anyone anticipated, and the more prosaic portions of the referendum were voted down. A “high-gear advertising campaign…managed to turn the negative vote around” on the library. It was clear, however, where the credit was due. “We have the black community to thank for the new library,” Jackson said. A few weeks later, in his State of the City address, the mayor was more diplomatic, attributing the success of the new library campaign to “the efforts of a marvelous, determined, interracial coalition of Atlanta voters.” But Jackson knew better than most how much Atlanta’s library system owed to African-Americans.

What was once the Dinkler Plaza Hotel, the site of so much racial drama in the 1960s, is now an impossibly non-descript parking deck. A Dunkin’ Donuts occupies the street-level retail space. The future of both the Dinkler and the Carnegie Library was to be in poured concrete (it was big at the time). Today, the subterranean rumble of MARTA trains pulling into or out of Peachtree Center Transit Station is a reminder that the real stories of places like this are deeper underground. Places like the dingy and poorly-lit basement of the Carnegie Library, which is the only place African-Americans were allowed to read books from the library’s collection. They were not allowed to borrow them until 1959.

In May of that year, a dapper African-American woman came into the library to ask for a library card. A French professor at Spelman College, she had spent time in France and had never had any problem in libraries there. She did not intend to start a revolution or to agitate in Atlanta; she simply wanted to borrow a book. The librarian was flummoxed. This had never happened before. He handed her the requisite form, the way librarians do. He told her to fill it out, and that they would call her.

In the meantime, then-mayor William Hartsfield was holding secret discussions with authorities quietly to desegregate the city’s public libraries. In classic Atlanta fashion, they chose not to make a fuss, issued the French professor her card, and made no public announcement about it.

But a few days later, the word got out. The Atlanta Constitution revealed the new library cardholder by name and address: Irene Dobbs Jackson of 220 Sunset Avenue, NW. Irene Jackson was the daughter of John Wesley Dobbs—the leader of the city’s thriving African-American business district—and mother of Maynard, the future mayor who would manage to get a new library built on the site of the old one where his mother had become the first African-American in Atlanta to hold a library card.

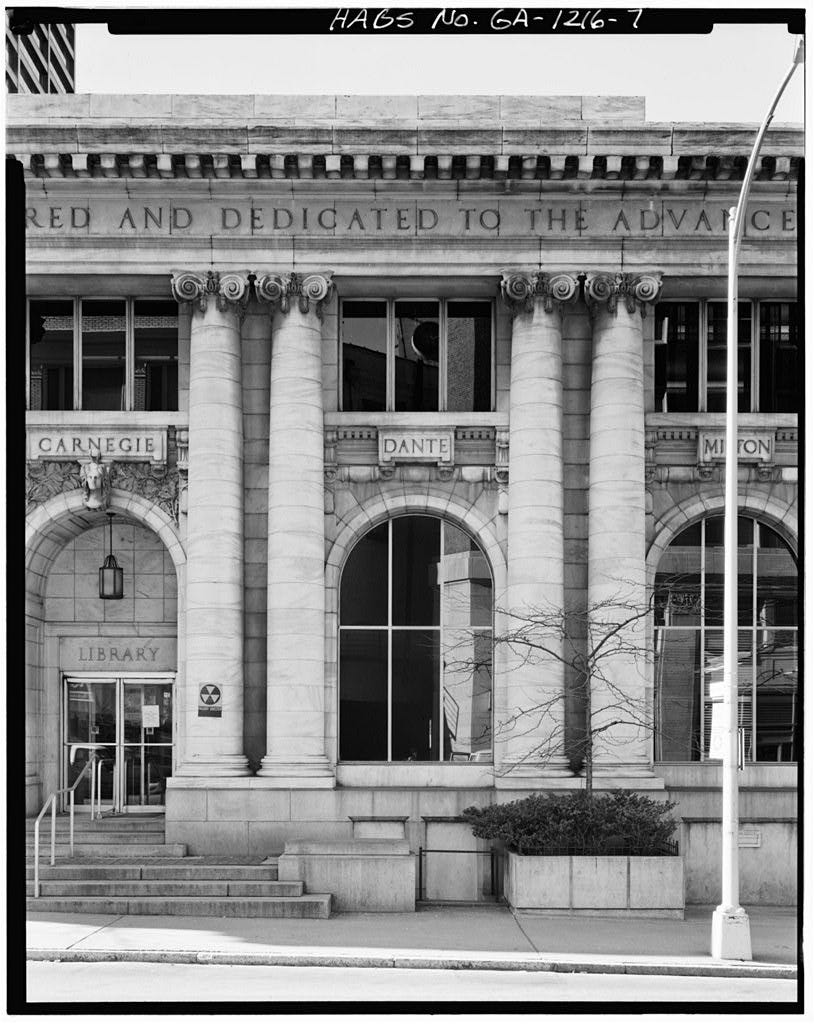

220 Sunset Avenue is not a well-known address, but it is next to one. In 1965, Martin Luther King, Jr. and Coretta Scott King bought a house at 234 Sunset Avenue, next door to the four-unit apartment building built by Maynard Jackson, Sr., in 1949, and home to the Jacksons until Irene sold the building around the same time. Arguably the two most influential people in the city during the second half of the twentieth century were effectively next door neighbors.

![The former home of the Maynard Jackson, Sr. family at 220 Sunset Avenue in Vine City. [Photograph by Casey Sykes for the Atlanta Journal-Constitution] The former home of the Maynard Jackson, Sr. family at 220 Sunset Avenue in Vine City. [Photograph by Casey Sykes for the Atlanta Journal-Constitution]](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/w_1456,c_limit,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fbucketeer-e05bbc84-baa3-437e-9518-adb32be77984.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2Fe8b58943-0ec9-4fbc-a8f0-07d84220f2ee_800x533.jpeg)

The King Center purchased the property early in its history, and in May 2019, the King Family decided to demolish the decaying apartment building. The structure is in terrible shape, and the site could become a parking lot when the National Park Service takes over management of the King home. The fate of the building is currently in limbo, but it could very well meet the same end as the Dinkler and the old Carnegie library.

Of course there are no markers anywhere on Forsyth or Williams or Sunset to point any of this out. Atlanta’s history remains mostly below street level. Whatever the fate of historic structures and their preservation in Atlanta, however, public memory here remains critically endangered. In a May 2019 press release, The King Center claimed that it “had no knowledge of the Jackson family living at 220 Sunset Avenue and was unaware of the possible historical connection,” and decided that the building was “only relevant to history because it temporarily housed The King Center at its inception while our founder, Mrs. Coretta Scott King, built our current site on Auburn Avenue.”

Amnesia has been culturally, economically, and politically advantageous to whites in “the city too busy to hate”—and everywhere else in America—but the tendency to forget that which is not beneficial to our self-image, and to think of history only in terms of its relevance to ourselves, is common to all of us.