Outlander

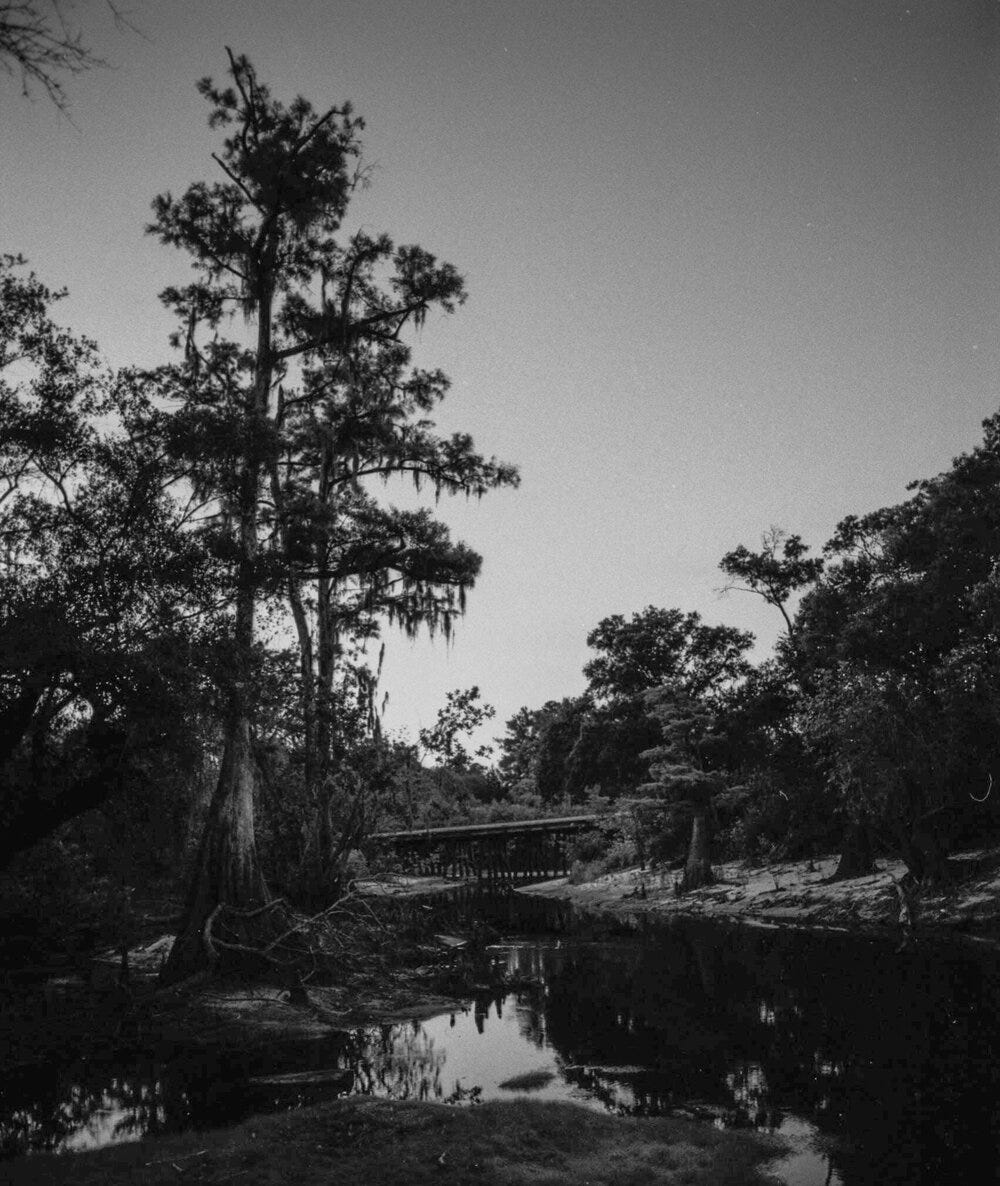

The frontier between Georgia and Florida is only clear until about Moniac. Since 1872, the state line has followed the Orr-Whitner Line to the west, but do not be deceived. On the map it appears straight and definite, but it is an abstraction. You wouldn’t know you’d even crossed it unless signs told you so. Only the St Marys River, which forms an appendix-like projection in southeastern Georgia, is a real, physical border, determined by nature and not a committee. Deep black, almost still, framed by longleaf pine and live oak, the St Marys forms the boundary between the two states for about 130 miles. You would know if if you crossed it. Harry Crews did so as a young boy from Alma, Georgia, relocating with his family to Jacksonville. For him, the “St. Marys River was a border that went beyond fascination.” It was the marker between the rural and urban wilds, between home and a foreign land, “all the time keeping everything that was Georgia away from everything that was Florida.”

This region of south Georgia/north Florida is in truth a boundary-less region. The actual line between the two states is porous and indistinct like the mushy peat-bottom of the Okefenokee Swamp. It’s easy to feel alienated here, disoriented. One possible reason why so many writers and thinkers have sought it out is for the porosity of its borders. For Crews, the boundary between “everything that was Georgia” and “everything that was Florida” was figurative more than geographical. It delineated two differing existential states: one of belonging, one of estrangement. The Okefenokee marked that frontier for Crews, who spent almost his entire life on either side of it.

The value of the Okefenokee was well-known to indigenous tribes, but—as with most things—white folks had to be educated. They came to the swamp looking not for paradise so much as for profit, and began concocting ways of draining it, putting a railroad through it, and cutting lumber from native cypress trees a millennium old. White engagement with the swamp was almost entirely subtractive: draining, cutting, selling, withdrawing, forcing out. White southerners—excluding the ones who lived in the swamp itself—typically viewed the massive swamp as a menace of nature to be mastered and controlled, drained into submission.

That was the way of it until a biologist from Cornell visited. Francis Harper—along with his elder brother Roland—had been advocating for the swamp for a while already, but it wasn’t until 1912 that the Harpers visited themselves as part of a Cornell research team. For the next twenty-five years, the Harpers became the most powerful advocates for the Okefenokee, and their influence saved the swamp from almost certain death. Francis’ wife Jean had been a tutor to the children of President Franklin Delano Roosevelt—who had a close relationship with Georgia already—and through the Harpers’ efforts, the Okefenokee was spared a proposed canal connecting the Gulf with the Atlantic and a tourist highway through it (supported by many at the time—including Clark Howell, high-powered editor of the Atlanta Constitution, who thought the highway would contribute to the swamp’s preservation). In his column for the Constitution, “In Georgia Fields and Streams,” H. A. Carter of the Georgia Naturalist Society wired his enthusiasm for the Okefenokee from south Georgia to Atlanta readers in the mid-1930s. Carter had drunk the swamp water: “it’s in my blood now,” he wrote.[1] He became one of the Okefenokee’s most ardent defenders in Georgia and an enthusiastic apologist for its preservation. Ultimately, FDR got into the game himself, and in 1937 designated the swamp a National Wildlife Refuge.

That December, Hal Foust, the auto editor for the Chicago Tribune, stopped in at Lem Griffis’ Fish Camp in the Okefenokee on an epic family road trip from Chicago to Key West and back. The itinerary was supposed to take him along the Gulf Coast from New Orleans to south Florida, but something drew him off-course, and into the swamp. It wasn’t easy going for a car and trailer on mostly unpaved roads: “In places the front axle plowed the high center of loose earth with the engine in low gear.” Road travel in 1937 was not what it is today, obviously, and also often depended upon the Jim Crow social stratification that even a Chicago journalist could count on:

Shovels and the brawn of six Negroes were needed to move the outfit in one place. At another the car had to leave the roadway to smash its way through sapling pines four to eight feet high and to ford a ditch with two feet of muddy water.

1937 was something of a high-water mark for American interest in the rest of the country, and especially for auto travel. It could be regarded, for convenience, as the birth year of the American Road Trip. The period from 1936-38 marks the first edition of The Negro Motorist Green Book, the first Stuckey’s, the publication of the first WPA Guide, and its cousin, The Rivers of America Series, which partook of the same wayfaring national curiosity of the WPA Guides. Conceived and edited by Constance Lindsay Skinner and ultimately consisting of sixty-five volumes over thirty-seven years, the series did for American estuaries what the WPA Guides did for American roads. (Skinner herself died at her desk while editing the sixth volume, on the Hudson by New Yorker Carl Carmer, the author of a famous 1934 outlander account of Alabama, Stars Fell on Alabama.)

The third volume in the series, published in 1938, Suwannee River: Strange Green Land, was written by a botanist from upstate New York named Cecile Hulse Matschat. The book is an evocative description of the land, its history, patois, and inhabitants, human and otherwise.

In the weird, hobgoblin world of the bays there is perpetual twilight. These bays are flooded forests of close-growing cypresses mixed with a few other trees. They stretch away from the prairies and runs into unexplored depths of shadow and mystery. Even at midday, with a brilliant sun overhead, only an occasional ray pierces the thick green roof of the jungle, spotting the brown water with flecks of gold and lightening the blue of the iris that blooms in the marginal shallows. The bottle-shaped trunks of the cypresses, often twelve feet in diameter at the base and a scant two feet in diameter above the swelling, where they begin to tower symmetrically toward the sky, gleam in tints of olive, silver, violet, and odd greens and blues. Their dark roots protrude above the surface of the water, either arched like bows or in groups of knees. Seeing this malformed forest in the strange green light, one might expect it to be the home of gnomes, with beards and humps. As a matter of fact, it is inhabited by much more sinister personalities.[2]

Suwannee River did much to contribute to the mythos of the Okefenokee as a region removed from the rest of the nation, sometimes forbidding and sometimes diffident about visitors. Matschat writes as a self-conscious outsider. To the locals she becomes known as “Plant Woman.” When one local asks her where she is from, she is met with a characteristic response:

“New York.” The woman sat upon an empty box. “Have you ever been there?”

“Nuvver heerd of hit. Don’t take ary truck with the outland.”

But outlanders took a lot of truck with the swamp, hauling off hundreds of millions of board feet of cypress timber until 1930. In one of a series of egregious moves, former Confederate General John B. Gordon sold off the swamp when he was Governor of Georgia, initiating nearly a half-century of predatory logging. The Suwannee Canal Company built railroads through the area, and began systematically draining the swamp, destroying the ancient cypress forest to sell the timber. Eventually the Federal Government bought the property back from the lumber industry, and made it a National Wildlife Refuge in 1937.

The closest the Okefenokee has to local literature is the novel Swamp Water by Vereen Bell, published in 1940. Bell was a native of Cairo a hundred miles to the west—in the same latitude as the swamp but by the latter’s standards still the “outland.” Bell’s book was made into a 1941 film for 20th Century Fox directed by the great French auteur, Jean Renoir. The film was shot partially on location in the Okefenokee, and represented the first opportunity for many people to see the swamp for itself. Renoir became infatuated with the people of south Georgia and “the land where nature is at the same time soft and hostile.”[3] But his experience with Fox soured him on the American movie industry, and he likely sympathized with “Georgians [who] think of Hollywood as a far more distant and bizarre place than France.”[4]

In 1941 Renoir took a tour of the swamp with local fisherman and unofficial Charon of the Okefenokee, Lem Griffis. (Griffis’ son Alphin still lives in Fargo, where he runs a fish camp and has inherited his father’s role as the area’s de facto raconteur-in-chief.) Renoir’s movie, like Matschat’s book, exhibits a particular fascination for the folk-speech of swamp people, but the filmmaker did not find the swamp to be nearly as sinister as Matschat: “In the heart of the swamp I saw a child of ten years fishing all alone, quite peacefully—and this in a place reputed to be the haunt of the very biggest alligators.” When the film premiered in nearby Waycross, it drew a bigger audience than Gone With the Wind had done two years earlier.

But no one communicated that particular strain of American speech more widely than the outlander Walt Kelly, a native of Philadelphia whose comic strip about a swamp-dwelling possum named Pogo ran nationally for almost 27 years. Entirely free of human characters, Pogo contributes to the swamp’s sense of otherness even as it diminishes—or displaces—its famous sense of menace. If it weren’t for northern “outlanders” like the Harpers and Kelly, who recognized the uniqueness of the Okefenokee and campaigned for its preservation, the swamp might not exist in the form it does today.

The same is true of the general area around the Suwannee River watershed, extending from the Okefenokee to the Gulf of Mexico: it is a region whose literature is mostly the work of outsiders, visitors or transplants who pass in and out of the bright light and deep shade of north Florida, sometimes returning with stories of their adventures, sometimes pilfering the area’s rich and evocative ethos to ornament their own work, sometimes staying to tell the stories of the region itself, and its people. It has been this way ever since Peter Martyr d’Anghiera recorded accounts of returning explorers in Spain in 1520, and since white settlers began steadily forcing indigenous people out.

North Florida has yielded a surprisingly wide range of authors, some of whom actually came from there. But not all of them stayed. Lillian Smith was born in Jasper, just across the Orr-Whitner line from Echols County, Georgia. Her 1948 book, Killers of the Dream was an unlikely and prophetic critique of the racist culture of the American South published. She was often a voice crying in the wilderness, castigating her contemporaries for romanticizing the past and ignoring the evils of racism. While a prominent group of male poets and thinkers centered at Vanderbilt known as the Fugitive Poets or New Agrarians were calling for a recovery of an “agrarian” way of life in the South, Smith called them to account for turning away from the pernicious realities of Black life under Jim Crow, and seeking refuge in “ancient ‘simplicities.’’” She did not cotton to their nostalgic sensibility, and recognized the danger of their sentimentality: “No writers in literary history have failed their region as completely,” she said of them. She boldly upbraided them for their “failure to recognize the massive dehumanization which had resulted from slavery and its progeny, sharecropping and segregation, and the values that permitted these brutalities of spirit.” Her own art dared to do what many of her white male counterparts’ did not: confront directly the dark truth of those brutalities, as in her debut 1944 novel about a lynching, Strange Fruit.

But Florida couldn’t keep Smith. Her fate followed that of naval stores, for decades an economic engine of this region. When his turpentine business fell apart, her father relocated the family to Clayton in the Georgia mountains, where she directed a summer camp for girls from 1925 to 1948, teaching them about African-American history, and exposing white children to the legacy of white supremacy long before being “woke” became a thing.

Florida couldn’t hold James Weldon Johnson, either. The first Black Executive Secretary of the NAACP and author of The Autobiography of an Ex-Colored Man, Johnson grew up in Jacksonville but during The Great Migration left the South for New York after attending college in Atlanta. His 1899 poem, “Lift Every Voice and Sing,” became the text for the “Black National Anthem.” In Johnson’s Autobiography—a fictional account based on his own lived experience—the mixed-race narrator negotiates what Johnson’s colleague at the NAACP, W.E.B. Du Bois, famously called “the color line.” In the narrators’s words,

this is the dwarfing, warping, distorting influence which operates upon each and every colored man in the United States. He is forced to take his outlook on all things, not from the viewpoint of a citizen, or a man, or even a human being, but from the viewpoint of a colored man.

As the narrator of Autobiography moves from Georgia to Jacksonville to New York, he crosses over the color line and back again, mostly racially incognito. He “passes” as white, just as he passes “from one world into another.” Johnson’s narrator is an outlander to stable racial essences: neither fully Black nor fully white, his double-identity is both curse and cover. He experiences both the advantages and burdens of an identity whose fluidity enables him to “choose” whiteness over “blackness” in a bid for social mobility.

Zora Neale Hurston was born in Alabama but moved to Eatonville in central Florida when she was young. In the late 1930s, Hurston worked for the Florida Writers’ Project and contributed to the WPA Guide to Florida. She is one of a very small handful of individuals—possibly the only one—to have both contributed to a WPA Guide and be cited in one. The section on her hometown of Eatonville—“one of the first towns incorporated by Negroes in the United States”—cites at length from Hurston’s description of Eatonville in her now-canonical novel, Their Eyes Were Watching God, published just two years before the WPA Guide.

Hurston is exceptional in many ways, not least because she is one of the few literary figures from north Florida who was raised there, and remained. The literary legacy of north Florida is largely the product of in-migration, mostly of whites from the northeast. Sometimes they lingered for a bit and went back home; sometimes they came to stay, like Hurston’s fellow novelist and friend Marjorie Kinnan Rawlings, who moved to the tiny hamlet of Cross Creek in 1928, where she began writing fiction.

Originally from Washington, DC, Rawlings was a contemporary of Lost Generation writers like Ernest Hemingway, F. Scott Fitzgerald, and Thomas Wolfe, with all of whom she shared an editor in the legendary talent-hound, Maxwell Perkins. Her novel, The Yearling, won the Pulitzer in 1939. She was every bit their literary and hard-drinking equal: she cussed like a drunken sailor, and drove like a bat out of hell. And like Fitzgerald and Wolfe, she flamed out early.

Rawlings’ home in Cross Creek is now preserved as a state park. It sits on an isthmus between Orange and Lochaloosa Lakes. Nearby, fishing boats put in at a boat ramp. Entering the property through a thick hedge, you meet a sign that reads:

It is necessary to leave the impersonal highway, to step inside the rusty gate and close it behind. One is now inside the orange grove, out of one world and in the mysterious heart of another. And after long years of spiritual homelessness, of nostalgia, here is that mystic loveliness of childhood. Here is home.

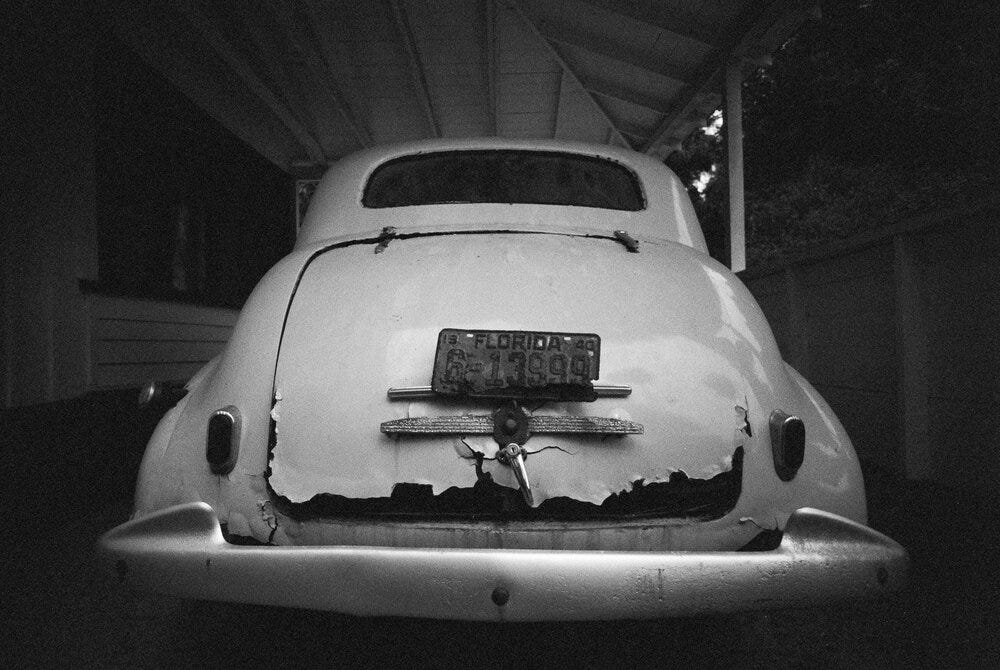

The grounds are like a north Florida version of Flannery O’Connor’s Andalusia: chickens free-range it around the rustic hen-house. Spanish moss dangles from a clothesline like the morning wash. The docent on this day, paunch-bellied, barefooted and appropriately transplanted from New York, hands us a paperback copy of The Yearling. Like so many before him, he’s fallen under the seductive spell of this area. The screened-in porch where Rawlings wrote at a table made by her second husband supports a reproduction of the typewriter she used. Not included in the restoration is the brown-bagged whiskey bottle Rawlings kept by her side as she wrote, nor the role played by Idella Parker, Rawlings’ domestic servant, in looking after Marjorie, or literally picking her up off the floor. Outside, under a covered porch, the yellow 1940 Oldsmobile that Rawlings insisted on taking for a spin while under the influence. It may or may not be the same one that she flipped over on one of those joy rides, nearly killing her and Idella both.[5]

Rawlings’ fictional work gave a voice to the “cracker culture” of her adopted home, but it and her lifestyle were not exactly the product of a life of back-to-the-land solitude and manual labor—at least not her own. Rawlings’ storytelling—and eating and drinking—were enabled by the largely anonymous work of Black laborers, who Rawlings often implored to sing spirituals for the entertainment of her white guests.[6]

After her death in 1953, Rawlings’s home was donated to the University of Florida. Later that decade, as a student at the University, Harry Crews and his housemates at what they called “Twelve Oak Bath and Tennis Club” used the Rawlings home as a regular retreat from Gainesville. They drank in the spirit of Rawlings, and also a lot of actual spirits. Cross Creek was in a dry county, so Crews and Co. smuggled Heaven Hill bourbon from a neighboring county, and holed up in Rawlings’ home to get lit, talk shit, and stumble awake in the morning to give hungover tours of the house to visitors.[7] An ex-Marine who attended college on the GI Bill, Crews himself ultimately bought a cabin not far from the Rawlings place. He spent his professional life at the University of Florida, but he was always trying to get Bacon County, Georgia back. But in the lecture rooms and departmental meetings in Gainesville, he realized his alienation from that world:

For half my life I have been in the university, but never of it. Never of anywhere, really. Except the place I left, and that of necessity only in memory. It was in that moment and in that knowledge that I first had the notion that I would someday have to write about it all, but not in the convenient and comfortable metaphors of the fiction, without the disguising distance of the third person pronoun. Only the use of I, lovely and terrifying word, would get me to the place where I needed to go.[8]

It was in Florida that Crews discovered that he was an outlander: from academia, from Gainesville, from himself. Somewhere around Cross Creek he found a way to pursue what he believed was a writer’s vocation: “to get naked, to hide nothing, to look away from nothing, to look at it. To not blink, to not be embarrassed by it or ashamed of it. Strip it down and let’s get to where the blood is, where the bone is.”

Perhaps Florida is built for discovering alienation from the world, from one’s history, from oneself. That discovery can be debilitating, which could help explain why so many planned communities exist in the state, as if to fence off the creeping sense that one is not really “where the blood is,” to inoculate oneself against the ever-widening impression of distance between the world and oneself, to cultivate in fertilized, irrigated, manicured, and leaf-blown security an feeling of belonging to a manageable world. On the other hand, that distance can be an occasion for what Flannery O’Connor called a “moment of grace.” It was for Harry Crews, who borrowed O’Connor’s term to give a name to an experience in Florida “in which I was allowed to see myself.” Florida’s literary history is mostly a story of outlanders, like Rawlings, who came here to make a home. For others—like Crews, Smith, Johnson—it became a means to discover a way to get there.

[1] Atlanta Constitution, 28 January 1935, p. 13.

[2] Cecile Hulse Matschat, Suwannee River: Strange Green Land (New York: Literary Guild), pp. 30-1.

[3] Alexander Sesonske, “Jean Renoir in Georgia: Swamp Water,” The Georgia Review 36.1 (Spring 1982), pp. 24-66, p. 30.

[4] Ibid.

[5] https://www.washingtonpost.com/archive/lifestyle/1993/01/06/together-but-not-equal/6a6da140-9c24-4adf-a068-fca6cac01ba4/

[6] Rebecca Sharpless, “The Servants and Mrs. Rawlings: Martha Mickens and African American Life at Cross Creek,” The Florida Historical Quarterly 89. 4 (Spring 2011), pp. 500-529; “Neither Friends nor Peers: Idella Parker, Marjorie Kinnan Rawlings, and the Limits of Gender Solidarity at Cross Creek,” The Journal of Southern History 78.2 (May 2012), pp. 327-360.

[7] See Ted Geltner, Blood, Bone, and Marrow: A Biography of Harry Crews (Athens, GA: University of Georgia Press 2016).

[8] Harry Crews, A Childhood: The Biography of a Place (Athens, GA: University of Georgia Press 1995).