Rumbling Man

He had been dead nearly ninety years when I first met Allen Candler on the ground floor of the north wing of the University Library in Cambridge, England in the late 1990s. I am sure we were both thinking the same thing: “What am I doing here? What are YOU doing here?” I am not sure what I was doing on the north wing—I mostly prowled the stacks on South Wing Four, where the theology section lived. But whatever I was looking for down on the far side of one of the greatest libraries in the world, it wasn’t the One-Eyed Ploughboy from Pigeon Roost.

From relatively meager origins I knew nothing of at the time, he seemed to have done pretty well for himself. Allen Candler may or not have been landed gentry in his own day, but he own a fair amount of real estate in the UL: around thirty or so stout volumes of the Revolutionary, Colonial, and Confederate Records of the State of Georgia. Impressive, if not exactly beach reading.

The truth is I knew nothing about Allen then apart from the fact that he had managed to get a relatively unspectacular county in the middle of the state named for him, and assumed that like most namesakes of counties, had probably done something equally prosaic to deserve it. Being white and holding office are not spectacular achievements in late nineteenth-century Georgia, but they are a good way of getting your foot in the named-county door.

It would be another twenty years before I learned that Allen was governor of the state during one of the most notorious lynchings in American history, and whose politics sought to entrench the establishment of white supremacy in Georgia. Since then, Allen has become a case study for me in the ways family and local memory can be dissociated from actual, very public history.

After his two terms as Georgia’s governor from 1898-1902, Allen retired to a much more sedate life as the state’s official archivist and compiler of records. It was kind of like being the Historian-in-Chief, but in reality the work probably required little more than an aptitude for filing.

The state records project would occupy Allen Candler from late in his tenure in the Governor’s Mansion until his death at his home on Edgewood Avenue in October, 1910. The final product is not the sort of thing that you would keep on your bedstand—unless your bedstand is the size of a pool table and you suffer from severe insomnia—it is largely an impersonal and pedestrian record-book, but it is the fruit of a highly personal quest, in which Allen Candler looked for himself in the stacks of the Library of Congress.

Before serving as Governor of Georgia, Allen represented Georgia’s 9th District in the US House of Representatives. What down time he had—which was a lot, apparently—he spent in the Library of Congress gathering and compiling facts about the family’s history in England and Ireland. Those hours led to a short biographical sketch of William Candler, an eighteenth-century figure who (insofar as he is still thought about) is generally accepted as some sort of important Irish personage in family history, possibly even a legend in a way, and is the patriarch of the Georgia Candlers or something. What little real knowledge of him still circulates in my family is due to a badly-faded and little-read typescript of “Colonel William Candler, His Ancestry and Progeny, by His Great-Grandson, Allen D. Candler.” Allen never intended the slim volume for publication, but it was published by Foote & Davies of Atlanta in 1896, while he was Georgia’s Secretary of State. In 1902, at the end of his tenure as Governor, he issued a revised edition, which is the one that I have, bound in a flimsy, red high-school grade presentation cover.

The text—anonymously transcribed in all likelihood by some anonymous aunt (who was probably named Florence)—in seventy-five typed pages, is itself a considerable labor of love. The circulation of the volume, along with interest in it, seems to have basically died out before the digital age; it remains a relic of both an age of hand-to-hand transmission by carbon copy and of a congenital propensity for cost-cutting. The copy I have is signed “To Asa,” but there are so many Asas in my family it could take a research grant to find out which one is meant (there are almost as many Florences). In some places the copier has failed, and there are white blanks that have been filled in with handwriting to simulate type, stitched back together like a precious broken vase.

In his introduction, Allen describes how he grew up away from his more well-known cousins, and did not meet any of them until he was an adult. Like the county named for him, Allen is an outlier to the Atlanta society to which my part of the family belonged at the time. He was born in Lumpkin County northeast of the capital city, in a town called Auraria, named for the gold that was discovered in them hills around 1830, and spent most of his adult life near Gainesville, where he is buried not far from Confederate General James Longstreet. The geographical distance from his own family history was generative for Allen Candler in two ways: it “actuated” a “natural desire to know what sort of blood flows in his veins,” as he wrote in the introduction; it also gave him a kind of critical distance from which to view the “truth of his family history.”

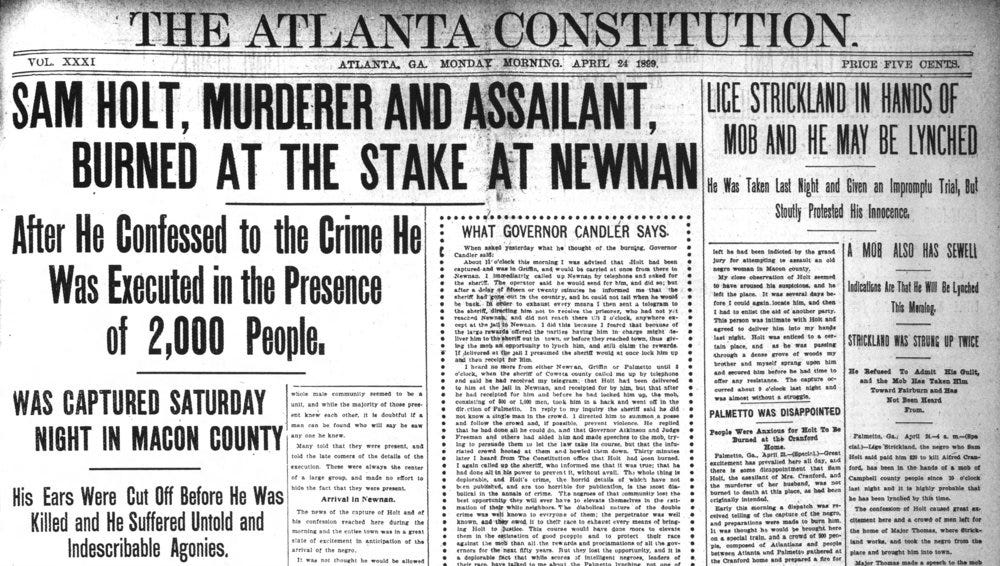

Despite what I know about him now, despite our differences in political sensibility, we have a few things in common. Like me, Allen Candler came in his forties to believe that the version of family history that he had received was seriously lacking, and began to seek out for himself where and whom he had come from; like me, he found some sort of refuge and wisdom in books and in great libraries; and—for totally different reasons—the lynching of Sam Hose turned out to be a defining moment for both of us.

But Allen’s pet project was born in an age when presuppositions about the study of history were totally different from those of my age. In the same library where I first encountered his volumes, I was reading books that undermined the very attitude towards history that Allen Candler breathed in with the air of the late nineteenth century. By “truth” of history, Allen meant “facts:” that which could be distilled from “family and official records,” “the most authentic historical publications, and, occasionally, unchallenged family traditions.” It is the same hard-tack understanding of truth as a series of facts to be surveyed from an objective, all-seeing distance that led Candler to edit, with Clement Evans, the three-volume encyclopedia Georgia: Comprising Sketches of Counties, Towns, Events, Institutions, and Persons. The volumes are a gold mine of information, and undoubtedly were a major resource for the WPA Guide to Georgia. But it betrays a perspective especially popular in the late nineteenth century, the age of the encyclopedia: history as compilation and sorting—a glorified form of paperwork—and the kind of distancing from the data of history that is inevitable when you reduce history to data.

Which leaves historical recollection divided into two main types: a reduction of history to “facts” from which the objective observer or author remains innocently removed, and the hagiographical biographies that turn historical figures into morality lessons for future readers. This is, arguably, what happened in the case of Allen Candler, who on the one hand transmitted to posterity an incalculably valuable resource of information, and on the other hand, contributed to the mythology of the Candler family that I inherited, in abbreviated form. It is no accident that the posture of historical distance popular in the late nineteenth century should lead to a kind of historical schizophrenia: both to a regime of demythologized “facts” and at the same time to thousands of shelf-feet of romanticized family myths distilled for future generations as models of good behavior.

Consider Allen Candler’s entry in the Biographical Directory of the United States Congress. It reads as an upward series of advancements laden with fact-words: born, attended, was graduated, promoted, promoted, appointed, promoted, engaged in, served, elected, served. They are words that signify action, but the only actions they seem to imply as important are ones associated with institutions of power. It’s not so strange: how many of us were taught that history is a series of wars, a sequence of the actions of a set of historical agents, that history is the cumulative effect of the deeds of “great men?” We may have rolled our eyes in school at these history lessons because they were boring; we should have rolled our eyes at them because they were hopelessly misleading and untrue. We didn’t know any better, though; I wasn’t educated enough then to know that this way of teaching history both conveniently concealed the contributions of lesser (non-white and non-male) actors and obscured the fact that those historical agents were human beings with real and often less than noble motivations.

For example: the quasi-mythological story about William Candler’s Irish origins came down to me like in a trans-generational game of Telephone: in one hundred years, the already stilted account given by Allen Candler had become a truncated scrapbook of fabulous factoids. In fact the story of William’s Irishness is so glaringly, egregiously untrue that I am grateful to have made it this far without attempting to curry favor with a real Irish person by telling them that I’m descended from William Candler of County Kilkenny.

William was Irish only in the sense that may have been born in Ireland, but how he got there was the more interesting, if less flattering, story. The Colonel William Candler who settled in Wrightsboro, fought in the Revolutionary War, served in the Georgia legislature and died in Richmond County at age 48, my great-great-great-great-great-grandfather, was probably born in Ireland in 1736. That part of the story—with considerably less detail—forms part of the family myth whose actual history pretty thoroughly undermines the illusion of Irishness. William’s grandfather was Lieutenant-Colonel William Candler of Northampton, fifty miles east of where I first met his great-great-great-grandson Allen in the library of the University of Cambridge, the same Allen who wrote that Lt-Col Candler “served under Cromwell in the conquest of Ireland, and afterward settled in the barony of Callan, in the county of Kilkenny, which had been given to him as a bounty for his military services, about the year 1653.”

William Candler was not Irish at all, but so thoroughly and colonially English as to be anathema to actual Irish, the men and women whom Cromwell’s troops savagely routed in 1650. Not even Allen Candler can hold back his contempt for Cromwell’s atrocities:

the annals of the world show no parallel among Christian nations to the cruelty and barbarities practiced upon the Irish people by Cromwell and his fanatical followers. In nine months the entire island was overrun. Three-fourths of the land was confiscated, and five-sixths of all the Irish people either perished by famine and the sword, or were exiled, and forty thousand of the arms-bearing men, driven from their homes by the invaders, had taken service in the armies of the kings of Spain and Poland, entertaining, doubtless, a hope that they might, by some turn of fortune, return and recover their beloved island, which was now reduced to a desolate solitude of want and misery.

(One hardly need note Allen Candler’s apparent obliviousness to the fact that similar atrocities were perpetrated on native peoples in the colonies, or to the reign of terror against African-Americans already in full swing at the time he wrote this.)

Cromwell is—obviously—no hero in Ireland; quite the contrary. The castle that was supposedly “given” to William Candler was poached from someone else.

Allen continues the bad news, citing a passage from John P. Prendergast’s 1868 volume, The Cromwellian Settlement of Ireland:

While the government was employed in cleaning the ground for the adventurers by making the gentry and nobility yield up their ancient inheritances…they had agents actively engaged throughout Ireland seizing women, orphans, and the destitute to be transported to Barbadoes [sic] and the English Plantations in America.

Allen Candler declines to cite the sentences in Prendergast claiming how this was good for both Ireland and the seized, who would “be made English and Christians.” In fact his citations become muddled here, but the original text of Prendergast reads that “at last the evil became too shocking and notorious, particularly when these dealers in Irish flash began to seize the daughters and children of the English themselves, and to force them on board their slave ships.” Allen Candler does not comment on the way in which Prendergast likens the bondage of white Irish people to the enslavement of Africans, this classic—and regularly debunked—staple of Lost Cause mythology would only have served Candler’s purposes. While he probably took the idea for granted, the idea still has currency. As recently as within the last few months, people I am related to have attempted to claim that “slavery was bad everywhere,” that “blacks owned slaves too,” that slavery wasn’t about race, and so on.

Even after the indentured servitude of the Irish was outlawed, the “statutes of Kilkenny” made it a crime for an Englishman to marry an Irish woman. For an officer like Lieutenant Colonel William Candler, the stakes were higher: intermarriage was high treason and punishable by death. Allen Candler cites one case—somewhat anachronistically, as it happened long before Cromwell, in 1584—where this law was enforced, against William Parry, LLD:

The court doth award and judge that thou shalt be had from hence to the place from whence thou didst come, and so drawn upon a hurdle to the place of execution; and there to be hanged and let down alive, and thy private parts be cut offe, and thy entrails be taken out and burned in thy sight, and then thy head to be cut offe, and thy body to be divided in four parts.

Allen Candler does not hide his disgust at this outrageously racist and procedure. But how could he write or read these words and not think of Sam Hose, whose murder was described in newspapers in similar terms? How could he not feel similar outrage at Hose’s “execution",” as the Constitution called it, which happened outside the law—unless, of course, he did not regard Sam Hose as fully human?

Allen Candler was not thinking of the actual fire that burned under Sam Hose’s body in 1899 but of the far more lyrical and more far-removed “fires of fanaticism [that] still burned in the bosoms of the Puritan lawmakers of England” when Lt-Col William Candler’s grandson Daniel, fell for an Irish woman.

The death penalty for the act had been repealed, but intermarriage remained a crime. In Callan in 1735, Daniel found himself in hot water:

He married a daughter of the despised Irish race and thus disqualified himself to sit in Parliament or to hold any office, civil or military, and put himself under the ban of social ostracism, and forfeited the friendship and sympathy of his own family. All that was left him to do, therefore, was to go with his wife for whose sake he had forfeited his citizenship beyond the seas, to seek a home and make for himself in the new world fortune and a name, and at the same time escape as well the ostracism of his own kindred and race as the penalty of the law.

Nostalgia and moralizing myths prevail here over historical truth, much less self-awareness. The defiance of “social ostracism” based upon race is supposed to be an inspiring example of the costs paid for courage, but only because Daniel Candler was white. Defiance of “social ostracism” is not OK if you are black in Georgia in 1899. Flouting convention is not virtuous if you are Sam Hose. And there was no need for African-Americans to voluntarily forfeit citizenship in Allen Candler’s Jim Crow Georgia, because the state was perfectly happy to do it for them.

Allen Candler’s nineteenth-century attitudes towards the study of history are now long-passé. The same cannot be said for many of the untruths of “history” that he reproduced or passed over in silence. He did not seem as interested in the way this less savory parts of family history might have shaped him, how he might have benefited from English pilfering of Irish property and the enforced bondage of Irish people, to say nothing of how—at the very time when he was writing the William Candler book and compiling the state’s historical records—he might still be participating in a white-colonial regime that enabled and even gave license to the torture and murder of black men. But Allen Candler was not interested in any of that; he was more into the romantic mythology around William Candler, which, while genuinely compelling, was founded on a smidge of poorly-transmitted historical truth.

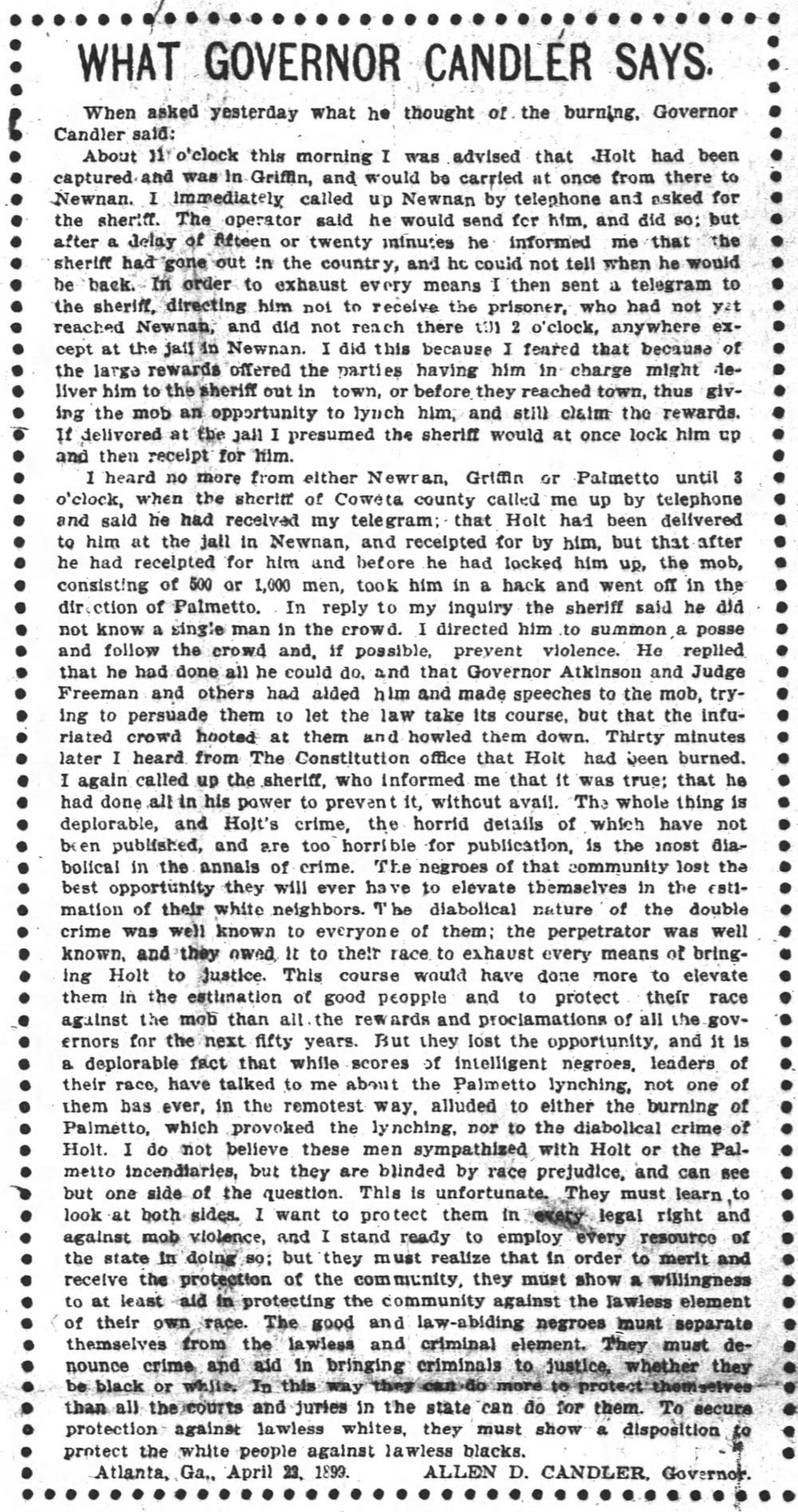

Only some form of dissociation can make it possible for Allen Candler to describe, on one hand, the alleged crime of Sam Hose as “the most diabolical in the annals of crime,” and on the other to call the spectacular torture, lynching, mutilation, and torching of Sam Hose by a massive mob of “respectable” white people simply a burning. The rhetorical imbalance should shock no one: it is entirely consistent with the majority of white Southern attitudes about African-Americans in 1899. But that it should come out of the mouth of someone so manifestly obsessed with the “truth” of history should give one pause.

The German philosopher Friedrich Nietzsche, who died while Allen Candler was in the Governor’s Mansion, believed that late nineteenth-century intellectual culture was “oversaturated” with historical knowledge. In his essay, “On the uses and disadvantages of history for life,” he said that

modern man drags around with him a huge quantity of indigestible stones of knowledge, which then, as in the fairy tale, can sometimes be heard rumbling about inside him. And in this rumbling there is betrayed the most characteristic quality of modern man: the remarkable antithesis between an interior which fails to correspond to any exterior and an exterior which fails to correspond to any interior—an antithesis unknown to the peoples of earlier times.

We become “walking encyclopedias.” The consequence, Nietzsche thought, is to “take things too lightly,” and the “habit of no longer taking real things seriously.”

This is not to say that an idea of history is responsible for Allen Candler’s racism, but it may help to make sense of how such a contradiction can exist in the mind of one so devoted to historical truth. Nineteenth century fashions in the study of history may have nothing to do with Allen Candler’s reluctance to discuss the “horrid details” of the lynching of Sam Hose, or the ease with which he was able to point the finger at “scores of intelligent negroes” who refused to mention “the diabolical crime of Holt [sic]” instead of towards the mob of white people who subjected Hose to unspeakable, ritualized terror. I do not know if the Sam Hose tragedy somehow triggered a later self-reflective impulse in Allen Candler, or if, combined with political fatigue, it prompted a personal movement towards introspection and self-knowledge. He wanted to know the real things about his own history less lightly. But what about Hose? Did he ever come to take those real things seriously?

In any case the exterior data of history—in this case, the drama surrounding Sam Hose—was all over the local and national press, to be eaten up and to rumble undigested in the bellies of millions of blood-thirsty newspaper readers.

I do not know if, on his frequent treks across the plaza from the Capitol to the Library of Congress, his prodigiously bearded face sternly set towards discovery, Allen Candler actually looked like a walking encyclopedia or if a casual by-passer could have heard emanating from his sturdy midsection the rumbling, indigestible stones of historical knowledge. I do not know whether or not, in the annals of family and state history, he ever found the self he was looking for.

The truths of family history, as he must have come to realize, amount to far more than the mere compilation of facts: it is possible to know who married whom, who begat whom when, to know where all the bodies are buried and still leave the question of one’s relationship to all that knowledge not just unanswered but unasked. As Allen Candler began to show me in the stacks of the Cambridge library, you can know every branch and twig and leaf of your own family tree and still not have the slightest clue who you are.