The Fighting Preacher and the Fat Bishop

When we set out on Tour Seven in July of 2019, we knew where we would end up, but not exactly how we would get there. The last stop before Atlanta was one of the few definite points on the itinerary: the intersection of Roscoe and Jackson Roads in Newnan, thirty-eight miles southwest of Atlanta. Somewhere near that crossroads was the site of an episode that marked a turning point in both the southern tours and my own self-understanding. The area near that intersection was once called Troutman’s Field, and on April 23, 1899, before a crowd of thousands, many of whom traveled on a specially-commissioned train from Atlanta, Sam Hose was lynched.

The details of the case are notorious, gruesome, and horrifying. And what I didn’t know about Sam Hose came to overshadow much of what has happened since I learned about him, and how my family was connected to this dark episode of local and national history. I think John and I both had a sense that we wouldn’t find much in the way of a memorial to that event at the corner of Roscoe and Jackson. But we were less prepared to find in our second stop north of Atlanta a completely unexpected confluence of forces that were touched by Sam Hose’s lynching, in a stately Victorian home at 224 West Cherokee Avenue in Cartersville.

Cartersville is about as far from Atlanta as Newnan, but in the other direction. Once a remote village on the Western & Atlantic rail line forty-three miles north of the capital city, the town has been either a beneficiary or victim of Atlanta’s relentless sprawl, attracting new residents who want to be close to Atlanta, but not too close.

It’s not especially new: Cartersville has long attracted luminaries, and at one time was home to some of Georgia’s most influential political figures. In the 1980s, Cartersville belonged to what city boys like me dismissively thought of as “the boonies,” but a disparaging appellation is about as much thought as I was willing to give it at a time when I was too ignorant to care.

The last stop before Cartersville was in Kennesaw—a mountain town well-known for its 1982 law mandating local residents to own a gun and near the Cherokee burial grounds for which the town and its adjacent mountain are named. If you come to Kennesaw expecting to find the sort of redneck white supremacists that movies and magazines have taught you to expect, Dent Myers’ Civil War Surplus and Herb Shop is happy to provide you with an unironic display of Ku Klux Klan paraphernalia and a Rebel flag to take home with you. If confirmation of that expectation is what you’re looking for, Dent is ready to oblige.

But turning the bend on South Tennessee Street coming into Cartersville, we are struck by a single roadside marker that hints at a more complicated picture. John—a professional historian who knows more about this stuff than I do—notices it instantly, and we pull off the road into a driveway leading up to a modest brick house on top of a hill. The house is older, but not that old. It’s clear that the house itself is not what’s important here.

John recognizes the name: Amos T. Akerman, which only lightly rings a very muted bell for me. It’s the first of many who knew? kind of moments on this trip, and an implication that what is about to follow is not what we’d expect.

Amos Akerman was born in Portsmouth, New Hampshire, but ended up in Georgia. An opponent of secession, Akerman joined the Confederate Army during the Civil War, but after it was over he joined the Republican Party, and became one of the state’s most prominent advocates for Reconstruction. In 1869 President Ulysses S. Grant appointed him Attorney General of the United States, and during his tenure Akerman led the federal campaign against the Ku Klux Klan, which resulted in the Enforcement Acts of 1870 and 1871, ending the Klan’s reign, for a time.

When we finish reading the historical marker for Akerman, it is already almost eight o’clock. In the fading light we head over to Oak Hill Cemetery to seek out his gravesite, but are unable to find it before the names have become all but illegible in the darkness. Early the next morning we return, and find a prominent granite tombstone to a famous scalawag in a part of the state not known for that kind of radical politics.

Thirty years after Akerman’s death in 1880, a local woman was still seething at the harsh treatment she believed Akerman endured in Washington. “It makes my blood boil to think of it even now,” she wrote. “This honest man, this upright lawyer, was actually hounded out of General Grant’s cabinet by men in Washington City…by the pimps and paid agents of [railroad robber barons Collis] Huntington and Jay Gould—and hounded in Georgia by our political desperadoes—organized Democrats.”

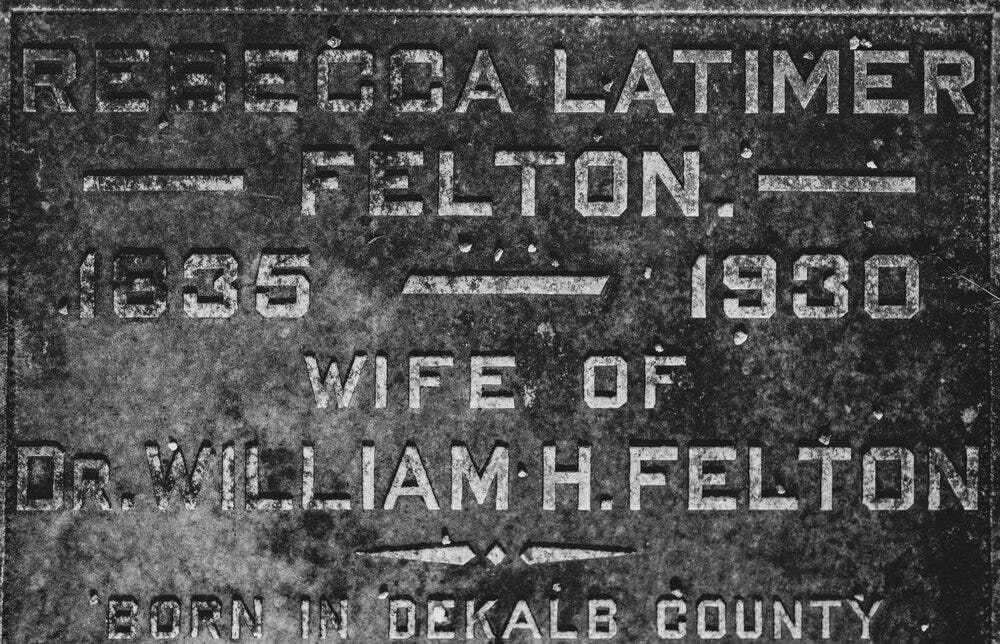

“I know what I am talking about,” she insisted. She had been a friend of Akerman in Cartersville, and after her death in 1930 she was buried not far from him in Oak Hill Cemetery.

Rebecca Latimer Felton’s tombstone describes her as “Leader in cause of women’s suffrage, Pioneer Director of Georgia Training School for Girls, Journalist, Lecturer, and Scholar.” And, in all caps: FIRST WOMAN UNITED STATES SENATOR.

Her tenure was short—she served for one day—but the symbolic power of the sight of the nation’s first female Senator was enough to draw legions of admiring women and supporters of the 19th amendment, passed in the same house three years earlier, into the Senate galleries for a chance to witness the historic occasion. But the throngs of well-wishers prove her undoing: after an over-long lunch, she was waylaid by admirers on her way back to the Senate chamber, only to find it empty, having adjourned for the day. She had lost her one opportunity to speak on the Senate floor.

But the next morning, she got her chance before yielding her seat to the new, duly-elected Senator from Georgia, Walter George. Wearing a tasseled and laced black dress stitched together from her own curtains, Felton said:

I commend to your attention the 10,000,000 women voters who are watching this incident. It is a romantic incident, senators, but it is an historical event…Let me say that when the women of the country come in and sit with you, though there may be but very few in the next few years, I pledge you that you will get ability, you will get integrity of purpose, you will get exalted patriotism, and you will get unstinted usefulness.

Felton’s speech “took down the house,” but it would be another decade before another woman filled a US Senate seat. Despite Felton’s progressive position on women’s suffrage and education, her views on race were far more in line with the Georgia mainstream in the late nineteenth century. Those views emerged most prominently around the subject of lynching.

In a speech before the Georgia State Agricultural Society at Tybee Island in 1897, she said that "If it needs lynching to protect women’s dearest possession from human beasts, then I say lynch a thousand times a week if necessary. The poor girl would choose death in preference to such ignominy, and I say a quick rope to assaulters." She went on:

As long as your politicians take the colored man into their embrace on election day and make him think he is a man and brother, so long will lynching prevail, because the cause of it will grow.

In a letter to the Constitution about a week later, Felton protested that she had been misunderstood. She was not, she argued, an advocate of lynch law as she had been depicted in the northern press. She evidently thought the following comment was supposed to correct that impression:

I am in favor of shooting down mad-dogs when their mouths are foaming after biting their victims, and when a human beast gets ready to this destroy my child or my neighbor’s child the beast should be taught to expect a quick bullet or a short rope. I would greatly prefer that the law should tie the rope about his neck, but if the law hides behind its "delay" while my child or my neighbor’s child perishes in its misery and ignominious condition, then I say there should be home-made law to meet such a case.

Felton’s words had power, and a long reach. By the following autumn, “Mrs. Felton’s Speech” on Tybee was still reverberating in the ears of African-American readers, especially in Wilmington, North Carolina. Alexander Manly, the editor of The Daily Record, a local black newspaper there, wrote a scathing response to Felton in which he accused the supposedly principled moral position of Felton against the outrages of “black brutes” of hypocrisy. White men had been having “illicit” relations with black women for centuries, he argued, some of those accused of rape were actually the products of white rape of black women. “Mrs. Felton,” he wrote, “must begin at the fountainhead if she wishes to purify the stream.”

White newspapers ran Manly’s editorial “ad nauseam” in the fall of 1898. In Wilmington the thirst for Manly’s “infamous assault on the white women” of North Carolina was so insatiable that the Morning Star reprinted the article at least forty times between the end of August and early November. The “storm of indignation” Manly’s piece aroused ultimately led to white mobs’ burning of the offices of The Daily Record, Manly’s flight from Wilmington, and the massacre of at least fourteen but possibly as many as sixty African-Americans. The slaughter in Wilmington initiated an explicitly white supremacist regime in the city.

Felton’s words had come home to roost. Despite criticism of her speech at Tybee, she remained intransigent. Three days before Sam Hose was lynched in Newnan, she wrote to the Atlanta Constitution, repeating her earlier appeal to “lynch a thousand a week or stop the outrage.” Hose—a.k.a. Sam Holt—was on the run at the time, fleeing for his life. Felton took the opportunity to fan the flames of lynch-lust:

It fatigues the indignation to mention it! Sam Holt needs and deserves no trial. When such a fiend abandons humanity to become a brute, then he shall be dispatched with no more cavil than would prevail with a mad dog’s fate, after he had bitten your child. I do not know a true-hearted husband or father who would not help to tie the rope around the beast’s neck, with less concern than he would shoot down a poor dog foaming with hydrophobia. In one case there is hellish intent, in the other a hapless disease. The dog is more worthy of sympathy.

Back in Cartersville, Felton’s body is buried a few yards away from a giant, pall-draped obelisk marking the grave of Sam Jones.

He is arguably Cartersville’s most famous local celebrity, even more well-known in his day than either Felton or Akerman. Jones is often described as the “Billy Graham” of the late nineteenth century. A circuit-riding preacher of the Methodist Episcopal Church-Southeast, he was a peer of “The Bishop,” Warren A. Candler, and the two often headlined Methodist revivals together. He was also a peer and, for not quite a week at least, a rival of Allen Daniel Candler, the Bishop’s first cousin. Jones mounted a short-lived and half-serious campaign for Governor of Georgia in 1898 on a platform of “simple, unadulterated, unpurchaseable, unbulldozable manhood.” His improbable bid was possibly calculated “to pressure Candler into supporting temperance education and statewide prohibition”—but he yielded to Allen, behind whom Jones threw his support, with one caveat. “I do not know of but one thing against him,” Jones said, “and that is I have heard he cusses.’”

Jones’ most famous convert was a riverboat man in Nashville who once attended one of Jones’ revivals, where, as Ryman put it, Jones “whipped me with the gospel of Christ.” Ryman turned his life around, closed his bars and devoted his attention and beneficence to Nashville’s down-and-out, and built the Union Gospel Tabernacle, a church to country music now known as the Ryman Auditorium.

Sam Jones’ home, Rose Lawn, is a swank and ornate two-story Victorian mansion on West Cherokee Avenue in Cartersville. It’s not the kind of house you would expect for a circuit-riding preacher in the late nineteenth century. It’s also not the place I would have expected to see the black dress Rebecca Latimer Felton wore on her one day as a US Senator, but there it is, laid supine in a glass-topped case like a corpse an open casket. A museum to Felton is upstairs, which includes a few of her books, her dresses, some photos, lots of laudatory prose about her pioneering role as a proto-feminist but no mention of her career as an unrelenting white supremacist.

The same is true of the materials in Rose Lawn related to Jones, who believed that “Law and order, protection of life and property, can only be maintained by the supremacy of the white man and [his] domination over the inferior race.” Despite insisting early on the the rule of law forbade mob violence, the Sam Hose case changed his mind. “Sam Hose deserved to be burnt, but I am in favor of the sheriff executing the criminal, except in cases like Sam Hose, then anybody, anything, anyway to get rid of such a brute.”

In Jones’ view, the dominion of the devil was chiefly narrowly circumscribed set of male behaviors—drinking, gambling, womanizing—and he was an evangelist for the gospel of good, clean, masculine living. In one of his sermons, he exclaimed:

Good Lord! Give us a strong, sinewy, muscular religion! This little, effeminate sentimental, sickly, singing and begging sort! My Lord God, give us a religion with vim and muscle and backbone and power and bravery!

Like Rebecca Latimer Felton, the practice of lynching did seem to trouble him. Most negroes were “peaceable, law-abiding citizens,” namely the ones “who know their place and keep it, just as the convicts at Joliet know their place and keep it.” He was initially opposed to lynch mobs on the grounds that they operated outside a divinely-instituted order of justice and/or vengeance. But he also objected to them because they were unmanly: “whenever I believe a man ought to be licked or killed for anything he has done to me or mine, I am going to go for him by myself…If I can’t lick him or kill him by myself, he will go unlicked and unkilled.”

The idea that lynching was at root a just vengeance for an unspeakable “crime against Southern womanhood” was apparently a popular sentiment in Cartersville. In 1902, Bill Arp (a.k.a. Charles Henry Smith), a Cartersville-based columnist for the Constitution, wrote, “the lynchings will not stop until the outrages do. When a Negro dehumanizes himself and becomes a beast he ought to be lynched, whether it is Sunday or Monday. Let the lynching go on. This is the sentiment of our people.”

In August 1903, while a speaker at the Bloomington Chatauqua in Illinois, Jones said that “this lynching business is not anarchy. If a mad dog or wild beast runs through the streets and bites some one the thing to do is kill it and kill it before it does any more harm.” The next month, Bishop Warren Candler weighed in on the lynching epidemic, and took direct aim at the reasoning of Bill Arp, “Old Mrs. Felton,” and Sam Jones. “In defense of lynching, it is sometimes said, ‘Stop the outrages that provoke lynching and the lynching will cease.’” Warren’s approach was more political than racial: “the law is more truly lynched than is the victim of the mob’s fury.” In his piece he articulated a fear of looming anarchy, the demise of the rule of law, and the collapse of civilization.

He also seemed to take a shot at Jones, in particular his comments at the Bloomington Chatuauqua:

the “chatauqua season” is a very dangerous time of the year…when platform managers, who have an eye for gate receipts only, are out hunting for “drawing” sensationalists, without regard for the kind of things that the sensation-mongers may pour out of their easy-acting mouths.

But a more likely indirect target was John Temple Graves, editor of the Atlanta News who, at a meeting in Chautauqua, New York convened to discuss “The Mob Spirit in America,” Graves claimed that lynching arose fundamentally as a response to “a crime against Southern womanhood.” Like Felton, Graves argued that “the cause must be removed before the effect is destroyed.” The reasoning was straightforward, if over-simple: when the rape of white women ceases, lynching will stop.

In his “Mob” speech in New York, Graves argued that the “logical, the inevitable, the only solution” to lynching was total separation of the races. The rule of the mob was not desirable, but it was “practical”: “Without the mob the South today would not be a place to live in,” Graves said. Hitherto, the mob had served “as the highest, strongest and most potential bulwark between the women of the South and such a carnival of crime as would infuriate the world and precipitate the annihilation of the negro race.” But stronger penalties would not be effective, because for Graves, “The masses of the negro are not afraid of death. They dare it nightly in their orgies and gambling dens. They have little sensibility. They have few ideals.” The Bishop was not persuaded. He cited a statistic that showed that out of 128 lynchings in a single year, only sixteen were the result of alleged “ravishing.” Unlike Felton, Jones, and Graves, Candler was skeptical of the party line on lynching that viewed it as a justifiable, if unfortunate reprisal for rape. The data, the Bishop suggested, did not line up, but Candler didn’t yet put his finger directly on it. “It is an outburst of anarchy, and not an irruption of righteous indignation against an atrocious crime.”

The Bishop already had a connection to Cartersville: his mother, Old Hardshell, relocated from Villa Rica to Cartersville in 1875 along with her sons Asa and John. Warren himself was named for Warren Akin, a prominent lawyer and statesman from Cartersville. But in 1903, The Bishop was becoming unpopular there.

Graves responded to Warren’s op-ed with a caustic retort of his own in which he called Candler “the Fat Bishop.” But Graves wasn’t the only one pissed off at him. In a September 15th letter on Atlanta News letterhead, John Temple Graves wrote to Rebecca Latimer Felton thanking her for an “enclosure” that apparently also took aim at Warren.

I had hit the Bishop so hard and had private information to the effect that he felt himself so hard hit, that I could not, in common chivalry, allow him to receive another blow so crushing as yours.

The “Fat Bishop” article was generally considered a most effective one and I have been patted on the back by nearly every methodist [sic] I have seen.

Graves’ reluctance to publish Felton’s letter suggests it must have been too inflammatory even for the typically unrestrained editor of The Atlanta News. To further irritate the Cartersville contingent, The Fat Bishop became even more direct about the causes behind lynching. He later concluded that “lynching is due to race hatred and not to horror over any particular crime.” Eventually the controversy faded away, but for a moment at least, Warren had become a pariah to white supremacists.

It was a momentous week in Cartersville, ending with a bizarre and otherwise ordinary tête-à-tête between two grown men that seemed to bear the weight of competing forces of history coming to blows. On September 6th, 1903, Sam Jones hosted his annual week-long meetings at the Tabernacle in Cartersville. Later that week, on the heels of his widely-circulated anti-lynching article in the morning edition of the Constitution on the 9th, Warren Candler preached at the Tabernacle, where Felton was likely in attendance. If The Fat Bishop preached about lynching, it didn’t make the news. The last word of the meetings belonged to Jones’ masculine gospel of toughness, and made headlines around the country. On the final day, Jones took umbrage with the local postmaster, whom Jones accused of selling wine. The two men got into a fistfight in the middle of town: Jones took a punch to the mouth and left a black eye on the face of the postmaster, Walter Akerman, third son of the Klan-busting former US Attorney General.