Truths Breathed Through Silver

March 2018 in western North Carolina. The pellucid, almost neon green of spring is just beginning to return, and the ground is damp and spongy from a very wet winter.

A month before, I was in Southern California, where nothing is ever damp or spongy, where parrots alight in the branches of unfamiliar trees, where a seemingly perpetual light strikes the arid rocks of barren mountaintops, and there never seems to be a reason to be sad.

I was in Pasadena to take part in the Culture Care summit hosted by The Brehm Center at Fuller Theological Seminary. My friend Mako Fujimura invited me to be a part of discussions each day about the theology of making along with my then-daily breakfast companions at the decidedly retro Conrad’s Restaurant, Curt Thompson and Esther Meek. I had the great fortune of spending a week rooming and often talking together into the night with Mako, hanging with and learning from Curt and Esther every day. I met inspiring people who are committed to “a vision of the power of artistic generosity to inspire, edify, and heal the church and culture.”

Whatever I went to California to do, I came away with A Deeper South.

It wasn’t part of the plan. Before I left for California, I had just sent off a manuscript of a comic novel about an imperious, high-church Episcopalian woman whose reign over the church picnic comes to a shocking end. I dusted my hands of it for the time being, and boarded a plane thinking it would be The Thing That Will Occupy Me for the next year or two. I could see it all unfurl before me: acceptance by a bigshot agent, publishing contract, revisions, book cover drafts, page proofs, launch party, book tour, and vacation in Tuscany. But that, obviously, is not what happened. I had gone to Pasadena expecting (or at least hoping for) a future orbiting around comedy. But when you spend a week in a great artist’s studio, you can forget about your expectations.

After being with people who make beautiful things with their hands, I began to envy a little bit their concrete connection with their own works of art and the things they make them with. As a writer, my materials are not very interesting: a keyboard and a screen. The actual materials are ones and zeros, and it is not easy to form an intimate relationship with bytes and digits. I started to wonder if I shouldn’t write the next book or essay by hand, in pen and ink. I didn’t. I continued typing on a laptop and sharing my ones and zeros with people over an electronic cloud that exists precisely nowhere.

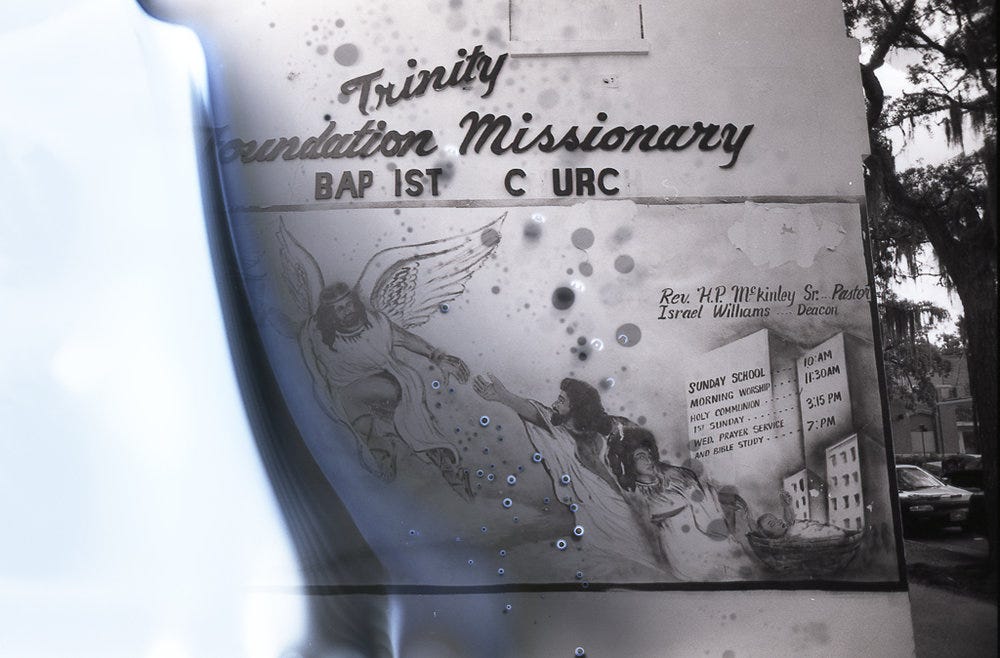

But I did start thinking a lot about film. In particular, about hundreds of short strips of mostly black-and-white negatives that I shot with my old friend John Hayes on a series of tours we took across the southeast from 1997 to 2004. We drove “Bessie,” his 1977 Ford F-150 with no air-conditioning, across the backroads of the south in August air so thick with humidity you could chew it.

It was a different era then, and more has changed between 1997 and 2017 than between 1977 and 1997. If we had taken a tour in 1977 when Bessie was new, not much would have been different from when we took our first trip, when the truck was twenty years old. We still would have shot on film, used paper maps, and, if necessary, called home with coins. But twenty years on from the first tour, everything is different. Almost no one outside of professional photographers shoots on film anymore. You can still buy hard-copy atlases and maps, but almost no one does. Almost all of this work has been outsourced to devices.

Everything in 1997 we did by hand: loaded film into the back of a camera, unfolded and refolded a map in such a way as to make it manageable and less unwieldy, with only the relevant part visible. We found places to stay and eat by happenstance and often took our chances, without the benefit of pre-screening Yelp or TripAdvisor reviewers. To travel in 2019 is to minimize risk as much as possible, to remove the possibility of disappointment. Not that long ago, this way of seeing the world wasn’t imaginable to anyone except maybe a few tech nerds in Silicon Valley. You took risks—small ones, to be sure—but risks that made any journey an exciting possibility the costs of whose discoveries were the occasional misfires and lemons that you were willing to endure for the chance at something you did not expect.

I have roughly a thousand photographs from the first five tours, mostly in Kodak Tri-X or T-Max. They have been, for years, in a dedicated black box, neatly organized into contact sheets and divided by trip and politely ignored. Seeing the photos again for the first time in years, it is striking how different film feels from digital imagery. My photographs are often not precisely focused. They are variably grainy and sometimes over- or under-exposed. During our fourth trip, a light leak emerged in the Minolta SLR I borrowed from my dad for the first tours (although “stole” is probably more accurate). Shots from rolls taken with that camera are streaked with mistaken light. Some rolls that I processed myself are incompletely developed, blotches of white splattering the negatives at the most inopportune points. Some of those images are beyond repair. But some of them, even in their imperfection, have a certain unrepeatable, unintentional beauty to them. They are singular in a way that only accidents can produce: weird, psychedelic almost, and photographically amateurish, but interesting in a way that I didn’t anticipate or even hope for.

Film has a texture that digital images cannot reproduce, even with the most sophisticated forms of technological imitation. Taking a picture on film also requires a different approach: because you know that you do not have virtually indefinite storage space, you have to be deliberate about each shot you take. You cannot afford to waste film, which is expensive to buy and to process. You are limited by the speed of your film; if you are shooting on slow 50 ISO film, you will have to adjust significantly if you decide to move indoors where the light is low. If you set up your camera to shoot inside, your images will have a different quality when you move into broad daylight.

Film photography is basically chemistry; digital photography is essentially electronics. Film is material in a way that digital photography is not. To work with film is to work with specific forms of matter, namely silver halides, microscopic particles of which are embedded in gelatin emulsion and coated onto strips of cellulose acetate. Silver halides are responsive to light, so when exposed to it, they become dark and opaque. At its most fundamental level, film photography is an atomic metamorphosis. None of this is to say that film photography is objectively better than digital. (I have no position on this debate that I am willing to share publicly except to say that as a medium, in every respect except convenience, film is unquestionably objectively superior to digital.) Digital photography has practically made artists of us all, or at least given us the illusion that we are. It’s an extraordinary and relatively inexpensive medium, and easily manipulable. Digital photography, however, does remove the element of risk involved in shooting film. You can afford to waste a lot of shots, and worry about editing them later. When shooting film, you have fewer chances, and must be more open to what you get. Much of the mechanics of digital and film photography are virtually identical: shutter speed, aperture, focal length and so on. But digital photography is essentially the transfer of algorithmic information, while film photography is a chemical action involving actual materials. It is the transformation of liquids and solids, rocks and minerals, into images.

In Pasadena I had the opportunity to witness Mako paint. Mako is a master of nihonga, an ancient Japanese style of painting that uses mineral pigments hand-ground from azurite, malachite, oyster shells, and so on. The pigments must be ground to a powder and then mixed with a glue made from animal hides before being applied to a canvas. The result is an image that is never quite the same from moment to moment. Because the paint on the canvas is composed of millions of prism-shaped mineral crystals, it refracts light in infinite ways, and never looks exactly the same twice (or even once). In this sense, Mako’s paintings are events, happenings, that have to be experienced, received, enacted in person.

In a way, film photography is not so different from nihonga. It depends on powdered minerals that respond to light in unpredictable, unmanageable ways. In other ways, it couldn’t be more different: film is made in a lab, not in a studio. It is produced by machines and not by hand. The capture of an image on film is instantaneous, not a distended process like painting. But at root something magical happens with film that also happens in Mako’s paintings, but does not with digital images: light strikes rock, and rock becomes more than itself.

Positive images emerge from negatives: in order to produce light on a print you need opacity, a first response to light. Light always comes first. Darkness is derivative and subsidiary, but they belong together. What actually happens in the processing of an image in film is a paradox: light produces darkness, and that darkness in turn makes way for light.

And light, thank God, is unpredictable.