[This week’s episode features a special excerpt from my forthcoming book, A DEEPER SOUTH: The Beauty, Mystery, and Sorrow of the Southern Road. Available for pre-order now!]

Following the Civil War, the US government laid down the conditions for the readmission of secessionist states in the Reconstruction Act of 1867. Section 5 of that act required each of those states to draft “a constitution of government in conformity with the Constitution of the United States in all respects, framed by a convention of delegates elected by the male citizens of said State, twenty-one years old and upward, of whatever race, color, or previous condition, who have been resident in said State for one year previous to the day of such election.” In 1868, like other Southern states, Mississippi wrote a new constitution that affirmed in law the Fourteenth Amendment to the US Constitution, which granted full citizenship and equal protection to the formerly enslaved. The Constitution was ratified by the people of Mississippi in December 1869, but it did not hold sway for very long.

Suddenly an entirely new voting bloc had emerged in Mississippi: African Americans constituted over 58 percent of the electorate. Within a little over twenty years, white resentment at Republican carpetbaggers and the new legal and political enfranchisement of a race still firmly held to be inferior had grown so intense that a new convention was called. Black people had gotten too much power, white Democrats argued. The 1890 convention was called for a single purpose: to reestablish white supremacy.

“Let us tell the truth if it bursts the bottom of the Universe,” declared [Constitutional Convention] President S.S. Calhoon. “We came here to exclude the negro. Nothing short of this will answer.” Indeed, so single-minded were the framers that Judge Chrisman was said to cry “My God! My God! Is there to be no higher ambition for the young white men of the south than that of keeping the Negro down?”

Among the more consequential of the new constitution’s provisions was the introduction of literacy tests and poll taxes at the voting booth, which effectively made it impossible for Black men to exercise their constitutional right to vote. It was a clever tactic, designed to restore white power entirely within the law, and it totally worked. Mississippi’s new refounding document became a model for other states, like Alabama.

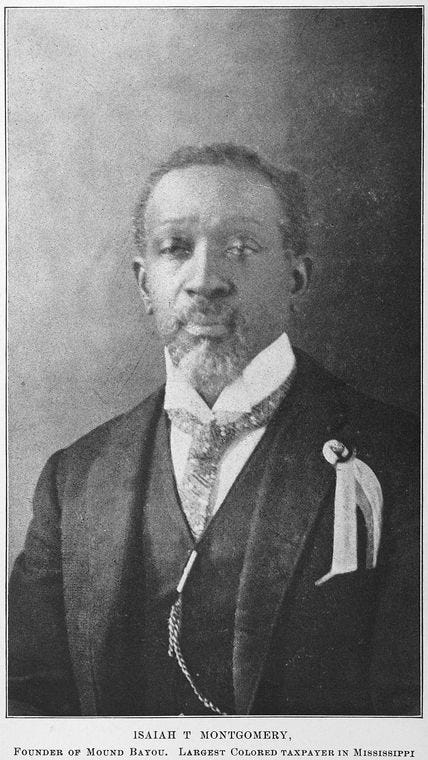

One hundred and thirty-four men sat in deliberation over the state’s new, overtly white supremacist constitutional convention. One of them was Isaiah T. Montgomery. The only African American at the convention, Montgomery was truly extraordinary.

Born to enslaved parents on Hurricane Plantation on a peninsula sticking out into Mississippi, at age twelve Isaiah became the personal secretary of the plantation’s master, Joseph Emory Davis, the older brother of Jefferson. Like the eccentric geography of the plantation itself, the elder Davis had tried to develop an unusual system for a plantation at the time: he raised not just highly profitable cotton, but also Indian corn and sweet potatoes. He raised hogs, sheep, and cattle. Davis bucked other trends, too: under the influence of the British utopian socialist, Robert Owen, he wanted Hurricane to be a model of humanistic labor in which the enslaved were given a highly atypical amount of autonomy, and he believed that his workers were best motivated by positive incentive rather than the lash. Davis established a court on the property, “eventually held every Sunday in a small building called the Hall of Justice, where a slave jury heard complaints of slave misconduct and the testimony of the accused in their own defense. No slave was punished except by a jury of his own peers.” Moreover, the plantation’s overseers were not allowed to punish a slave without the consent of the court. It did not always work out. When punishments were administered, they often resembled those one might find on any other plantation in the South.

But it was an undeniably radical vision of plantation management in its day, and clearly left a mark on the young Isaiah Montgomery. His father, Benjamin, ran the dry goods store at Hurricane. When Joseph Davis fled the plantation as Union naval boats moved up the Mississippi from New Orleans in 1862, Benjamin Montgomery took over operation of the plantation until Union soldiers took the Montgomerys to Cincinnati. By 1865 they had all returned to Davis Bend, where they operated something even more radical than Joseph Davis could have imagined: a thriving cotton plantation on the Mississippi River run entirely by African Americans.

Though by 1865 he could no longer be considered Joseph Davis’s property, he still did not own the land he managed—until Davis sold it to him. After Benjamin died in 1877, Isaiah took ownership of the plantation, but after the collapse of the cotton market the project at Davis Bend become no longer feasible. In 1887, Isaiah Montgomery and two other African Americans from Hurricane Plantation left Davis Bend for Bolivar County in the western Delta, where they implemented a kind of self- sustaining, Owenite community for African Americans, called Mound Bayou. It soon became one of the most thriving Black-only towns in the country, and home for Black desire so alluring that even white artists were taken in by it.

Mound Bayou, I feel blue and all in,

Mound Bayou, I can hear you callin’!

All my friends are lucky to be way back there,

If they knew what I’ve been through, they’d stay back there!

Mound Bayou, got to cover ground for

Mound Bayou, that’s the town I’m bound for!

Wish my arms were long enough, here’s what I’d do,

I’d reach and wrap them gently round my Mound Bayou.

Mound Bayou was the subject of a popular song written by Leonard Feather, a noted music critic and composer born into a well-to-do Jewish family in London. In 1942, backed by the British-born trumpeter Henry Levine and his Strictly from Dixie Jazz Band, a white woman from Mississippi named Linda Keene cut a record of the song for RCA Victor. In a classic move now well-known in the history of American music, her version takes the story of an extraordinary town created entirely by African Americans and turns it into a sentimental cliché about a quaint Southern town. The cover art for the album that Levine made for Victor, Strictly from Dixie, features a stylized image of a Black boy eating a watermelon.

That October Keene was playing the Patio in Cincinnati, singing “Mound Bayou” and evoking a wistful, ice-tinkling-in-the-gin-glass nostalgia of the Old South. The Enquirer described the subject of her “special song” as “One of those Shangri-la places where there are no jails, everyone sits around in the sun, and there’s always fried chicken on the table.” It’s safe to assume that most of the clientele in the Patio would have been surprised what they’d have found in the actual Mound Bayou. It is possible that Feather had seen as much about the real Mound Bayou as Stephen Foster had of the Suwannee River.

The actual Mound Bayou has diminished somewhat since its heyday; if someone were to write a song about the place today, it might not evoke the kind of longing for welcome that Feather’s song did.

We first came here in 1999. I am struck then by the extraordinary hand-painted signage that adorns almost every storefront. I shoot stills of Ray’s Bargain Spot, which advertises T-shirts, caps, stockings, snacks, and haircuts. A metal sign hanging out over the sidewalk, suspended by guy wires attached to the roof, calls the place “The Crowe’s Nest.” I try to capture the artful signage, but I do not really know what I am looking at. One poster in the window features the apparently immortal Bobby Rush.

The Crowe’s Nest was started by Milburn Crowe, a local activist and historian who devoted his life to preserving the story of Mound Bayou. His father, Henry, was one of the first settlers here. In the 1960s the Crowe’s Nest became a meeting spot for civil rights activists traveling through Mississippi, who would often stop in to talk with Crowe, eat some ribs, play a little poker, and drink some whiskey.

In 2018, I am looking for the Crowe’s Nest again, not because I know about the history of the place yet, but because of the signs. I remember it from a series of photographs from almost twenty years earlier, which I use as a cue. The building is still there, but all the old signs have been painted over, including the one for the “Crowe’s Nest,” which has been crudely scrawled with a can of spray paint.

Meanwhile, the home of Isaiah T. Montgomery on Main Avenue is less decrepit than it once was. Signs out front and orange fencing around betoken its forthcoming restoration, thanks to the National Trust for Historic Preservation.

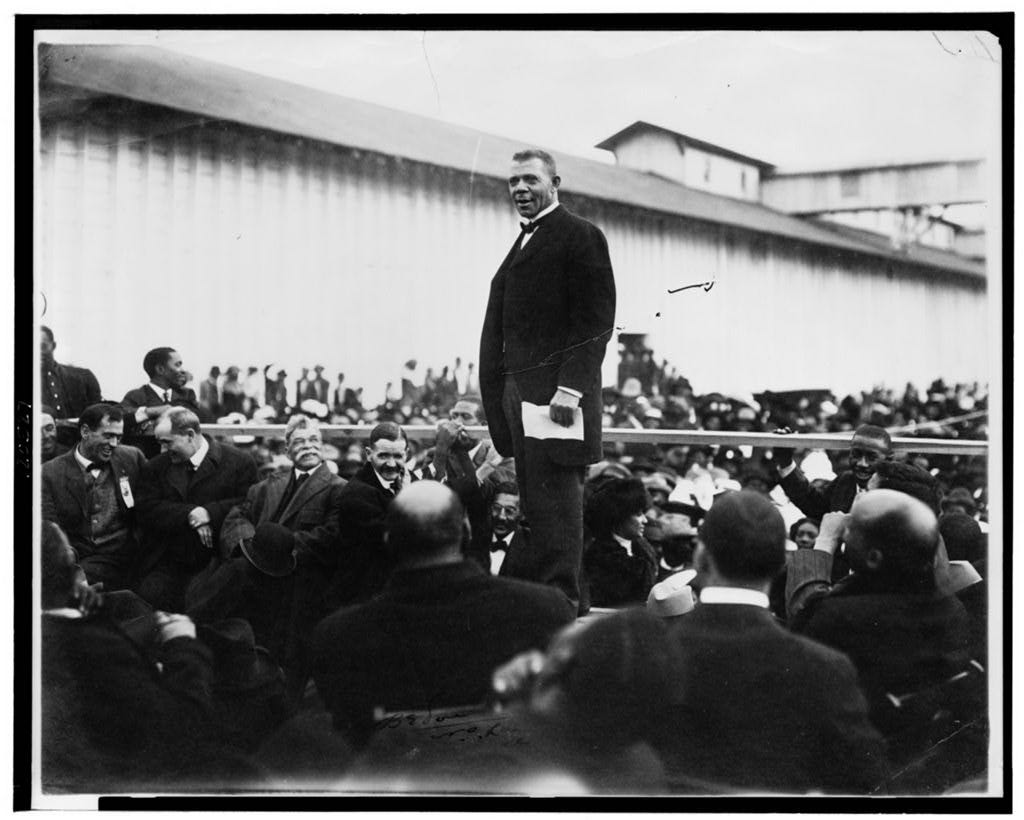

Montgomery’s vision for racial uplift in Mound Bayou shared a lot in common with the ideals of Booker T. Washington, who visited the town, wrote about it as a model of the classically Washingtonian values of “thrift and self-government.” Through the Tuskegee Institute Washington secured investments from white northerners in the settlement. Mound Bayou had effectively hitched its fledgling wagon to the Booker T. Washington express train.

Montgomery himself also seems to have had Washington’s pragmatic but limited aspirations for African Americans in a largely white supremacist culture. In his profile of Mound Bayou, Washington quotes Montgomery: “What we need . . . is an agricultural school, something that will teach the young men to be better farmers than their fathers have been. But, more than that, we need here a system of education that will teach our young men and women the underlying meaning of the work that is being done here.”

Like Washington, Montgomery was learned, eloquent, and inspiring, and regarded my many African Americans as a model for what a self-determined Black life could be. To many white people, on the other hand, he was proof of the aspiring, up-by-your-bootstraps ideology that simultaneously exalted people like Montgomery and ensured that their bootstraps not pull them up too far.

For all the exemplarity of the self-governed community at Mound Bayou, Isaiah Montgomery seems to have accepted the white terms of Black political life. He was held up as a hero to white folks because he was a successful Black man who knew his place.

That may not be how Montgomery himself saw it, but it was certainly one of the reasons why he was elected to serve as a delegate to the 1890 constitutional convention, which would prove the most consequential moment of his life. He delivered a “remarkable speech” to the convention, which drew comparisons between the power of Montgomery’s oratory, and that of Frederick Douglass. He conceded that Black folks had helped to build “the proudest aristocracy that ever graced the Western hemisphere,” but also wondered what it cost:

Sometimes, Mr. President, as I gaze over our broad acres, my heart would rejoice in the progress and glory of Mississippi, but a feeling of sadness represses my exultation, as the unanswerable question arises, How much of life, how much of privation, sorrow and toil has it cost my people? Perchance every acre represents a grave and every furrow a tear. And what have they by recompense?

Montgomery was no radical; he paid dutiful obeisance to the primacy of white culture and offered little legal objection to it. On the contrary, Montgomery described the Franchise Committee’s proposal to levy a poll tax, require a literacy test for voters as “adequate to restore purity to the ballot-box, and render it what the genius of our institutions demand that it should be, a free and untrammeled expression of the popular will.”

Montgomery knew that this would effectively disfranchise thousands of Black voters. He cited an illuminating statistic that plainly exposed the anticipated outcome of the new law:

Present voters, white . . . . . 118,890

This bill will restrict . . . . . 11,889

And leave a net white vote of . . . . . 107,001

Present voters, negroes . . . . . 189,884

This bill will restrict . . . . . 123,334

And leave a net negro vote . . . . . 66,550

Giving a white majority of . . . . . 48,451

If there was ever a moment when Mississippi state politics was on the edge of its seat, this was it. It could go either way. On the one hand, Montgomery could press the case against the “unquestioned white supremacy” of the convention and protest the move, stalling the whole convention and frustrating the white consensus. At this point delegates W. S. Farish, George Dillard, and P. Henry, who had contested the legitimacy of Montgomery’s election as a delegate and proposed that he be unseated, were surely squirming in their seats, their worst fears confirmed. On the other hand, Montgomery could yield, and confirm to all the rest of the delegates that in Montgomery’s election the convention had gotten its perfect poster child: a dutiful and submissive Black person.

It soon became clear which party was going to get their “I-told- you-so” moment. In the interest of “purity,” Montgomery entrusted the ballot to “the virtuous and intelligent voters of the State,” and waxed floridly on the promises of the franchisement clause for a restoration of order: “the grave dangers which called this body into being will be dispelled as the dewy mist of the morning by the rising sunburst of political liberty, which shall bring into renewed life the dormant energies of a new South and inaugurate an era of progress that shall rapidly bring our State abreast of any section in this broad land.”

With that, Montgomery threw his meager political weight but powerful consent—and with it, the symbolic consent of Mississippi’s Black voters—“to lay the suffrage of 123,000 of my fellow-men at the feet of the Convention.”

It wasn’t even a consent made in protest; Montgomery offered “a fearful sacrifice laid on the altar of liberty” in the belief that it would “restore confidence, the great missing link between the two races.” He could have stopped there, but he didn’t. He concluded his speech with a final gesture:

The greatness and chivalry exhibited by your race in springing from the lowest depths of barbarism to the position of dominators of the civilized world needs no commendation at my hands.

To them the world is indebted for the great triumphs of architecture, mechanism, art, literature and science, and for the perpetuation and dissemination of the ennobling principles of morality, Christianity and immortality.

One can only imagine how this must have swollen the hearts of Mississippi’s white delegates on the convention floor, but the New York World detected “a deep sense of relief and surprised wonder” among the audience at the “burning words” of the “dusky orator.” “That which the culture and the polish of Mississippi’s proudest had vainly tried to effect had been accomplished by this once slave—the exponent of a despised race.”

The gaslit parlors and breezy front porches of the white delegates that evening must have radiated with self-congratulatory giddiness at their triumph. For here in the flesh was all the proof that they needed for their own program of white supremacy: an industrious and eloquent Black man just educated enough to know his own place, exactly the kind of Black person a white planter or politician in Mississippi in 1890 could imagine living in racial harmony with, so long as he never forgot or tried to rise above his own station. While Jackson throbbed in the aftermath of Montgomery’s “noble speech,” it did not play as well in DC. Less than a month after Montgomery’s speech in the Mississippi capital city, Frederick Douglass delivered one of his own in the Metropolitan AME Church six blocks north of the White House. He was unsparing in his rebuke of Montgomery, arguing that he “has surrendered to a disloyal State a great franchise given to himself and his people by the loyal nation.” And that was just the beginning. He condemned Montgomery’s assimilationist attempt to kowtow to the white principalities and powers and was complicit in the national backtracking on the promises of Reconstruction. For all his criticism of Montgomery, he reserved his judgment for his act, not the man himself. “Yet I have no denunciation for the man Montgomery,” Douglass said. “He is not a conscious traitor though his act is treason: treason to the cause of the colored people, not only of his own State, but of the United States.”

For Douglass, the consequences of Montgomery’s concession speech would be wide ranging. He feared that the Mississippian’s gesture would be repeated across the South. But most revealing is the concession Douglass made to Montgomery, and his attempt to empathize with the circumstances that led to his great betrayal:

I hear in the plaintive eloquence of his marvelous address a groan of bitter anguish born of oppression and despair. It is the voice of a soul from which all hope has vanished. His deed kindles indignation to be sure, but his condition awakens pity. He had called to the nation for help—help which it ought to have rendered and could have rendered but it did not—and in a moment of impatience and despair he has thought to make terms with the enemy, an enemy with whom no colored man can make terms but by a sacrifice of his manhood.

Montgomery had, unwittingly, perhaps, and unavoidably, abetted the white supremacist revival in late-nineteenth-century Mississippi, and became a kind of prototype for later Black politicians (or aspiring politicians) who, for one reason or another, prove useful to the white status quo, who are celebrated by white Americans as a testament to a post-racial society and are tolerated as agents within the white establishment so long as they don’t say anything or advocate any policy that would militate against it.

We pull the car onto the capacious shoulder of Mississippi State Highway 32 east of Mound Bayou. A crop duster swoops low past the tree line and hovers a few feet above the cotton fields, letting loose a trail of pesticide. At the near end of the field it rises and loops back, and repeats the process. It’s what passes for free roadside entertainment in the Delta, but it is genuinely engrossing, this underappreciated feat of aeronautic gymnastics that happens on the daily here. It’s also archaeology in the air, and a reminder of a connection to our hometown.

Delta Airlines, currently the world’s largest airline in terms of annual revenue and one of the anchors of Atlanta’s New South economy, was founded in Atlanta in 1925, shortly after Asa G. Candler, Jr., offered the City of Atlanta a former racetrack south of downtown for use as an airfield. The forward-thinking and commercially minded Alderman William B. Hartsfield saw the potential in the plan, and the site eventually became Hartsfield-Jackson International Airport, the main hub for Delta Airlines. But it didn’t get to Atlanta until 1941. Originally called Delta Air Service, the future passenger airline behemoth started out as a crop-dusting operation built to combat the boll weevil, the nemesis of long-staple cotton. The Air Service’s most significant early client was the Delta Pine and Land Company, based in the heart of the region whence the airline derived its name.

The slogan du jour in my hometown is “Atlanta Influences Everything,” the latest in a long line of boosterish catchphrases going back at least to Hartsfield himself. But I am not sure it isn’t more accurate to say that the Delta influences everything.

Dear Pete,

I might be your Mom and otherwise biased but your writing is magical, riveting and ALWAYS educational and insightful... your recent piece is once again, powerful, riveting, historically and currently relevant and important.

We are SO proud of you and your wonderful writing as you continue to enlighten and educate!

Love beyond measure,

Mom and Dad❤️❤️👍👍