Well I still keep on wondering

Why is it I can’t find no mail

I keeps on wondering baby

Darlin’ why I can’t find no mail

Yes you know some crawling black snake

Must be done crawled across my trail

— Lightnin’ Hopkins, “No Mail Blues”

I am willing to bet that you never felt crossed by a black snake because your Gmail inbox was empty. Relieved, maybe, but not cursed. On the contrary: you are less likely to grumble about how little email you receive than about how much, and how much of so little consequence. We complain about how many emails fill our inboxes as if staging a protest against digital excess—Ugh! I have 1457 new emails this morning! I can’t even!—but we wear it like badge of self-importance, as if bloated inbox is a reassuring indication that someone, somewhere needs us for something. I mean, surely it is, right?

Forget the sheer volume of it all, though: as a medium, email is far too soulless to be worth singing the blues about. Unlike the actual mail, email is literally weightless. The mail carries weight: consequently, the lack of mail was at one time ominous enough for Lightnin’ Hopkins and, later, Memphis Slim, to suspect some inadvertent devilish spell as the cause for an empty inbox. The difference is not that few people seriously believe in the devil anymore (or the occult powers of black cats and snakes), but that few people still seriously believe in the US Postal Service.

I once heard an old Baptist preacher explain that the reason no one tells preacher jokes anymore is because we only joke about the things we take seriously. If that is true, then the fact that the mailman is no longer the object of satire in American culture is not an especially good sign. In the United Kingdom, “Postman Pat” is still the ingenious hero of a children’s television program that has run for forty-two years. Pat is an intrepid mail-deliverer for whom getting a parcel to its destination is an almost religious vocation, which he never fails to fulfill by any means necessary. In the United States, the last mailmen to occupy any significant place in the popular imagination were disgruntled, overweight, and lovable buffoons of prime-time sitcoms. Britain has Postman Pat and his Black-and-White Cat. We have Cliff Clavin and Newman.

It’s not necessarily a bad trade-off. Pat is a product of childhood fairy-tale and a counter-myth to the reality of the contemporary Royal Mail. Cliff (or Newman, take your pick) is an object of adult satire, a mollified Falstaff with a trace of his cynicism but without his excess. Since Cheers and Seinfeld both went off-air in the 1990s, no serious contenders have emerged for the role of leading on-air mail deliverer, which is interesting for what it says about the role the mail-person now holds in the public consciousness—which is to say, roughly, none. College professors often bemoan the distance between their cultural allusions and their students’ store of knowledge, which is usually measurable in decades, if not centuries. It is probably right, if a tad unrealistic, to lament that most college kids do not know who Sir John Falstaff is, but it might be just as worrying that they don’t recognize Newman or Cliff Clavin either.

I was informed recently by the United States Postal Service—through Facebook “post,” not a pre-sorted, pre-metered mailer—that the history of television includes a string of positive portrayals of mail carriers, most notably, perhaps, the impossibly cheerful Mr McFeely from “Mister Rogers’ Neighborhood.” The most recent example refers to Reba the Mail Lady from “Pee-Wee’s Playhouse.” But that was the early 90’s, and when put in the same paragraph, the names Pee-Wee Herman and McFeely do not exactly arouse the desired connotations for the intrepid mailman.

The post did not mention Newman.

By the time of The Simpsons, the mailman had become so anonymous that he/she no longer had a name (see Bart’s moniker, “the fe-mailman”). This decline may be due in part to what we ask the mail carrier to deliver for us. Sure, there are plenty of us who bemoan the demise of the personal letter, but few who have been consistently serious about it, except for fountain pen nerds and old people who can’t be arsed to figure out email. The triumph of email is simply a fait accompli, and if our sorrow over the death of the letter is tepid, it may be because, well, email is just so easy. The belligerents of the digital conquest of interpersonal communication, like the Visigoths in Ancient Rome, stole into the city of letters under cover of night and had subdued everyone to their universal dominion by sunrise. It was perhaps the most dramatic bloodless revolution within recent memory, and we yielded with only very sleepy resistance.

Even this little word—post—has become colonized by the digital revolution. The word once named some thing that came to your house, or something you dropped off in a blue or red box. The word has many other senses, the oldest of which is Old English for “a long, sturdy piece of timber.” The term “post” as in the “postal service” comes from a different source in Middle French: poste, or “a series of men on horseback responsible for transporting letters along a route.” A “post” now names something you do—and do all the time, whether on Instagram, Facebook, Twitter, whatever.

A whole genre of literature has, as a result, been a casualty of the digital empire. To cite one late example, The Selected Letters of William Styron appeared in 2012, but as a volume it is perhaps as curious for what it represents as for what it contains. Styron, who died in 2006, was probably one of the last novelists to have conducted the vast majority of his life’s correspondence with stamps. But the publication of that correspondence is a reminder that the genre itself is in its death-throes. It will not be long before “The Selected Letters” of anyone will disappear as a genre (or at least continue only in a spectral sense, in the same way that the “get mail” icon on your computer’s email app represents the very envelopes that app has rendered obsolete1). Maybe we shouldn’t have yielded this territory so lazily; maybe we wouldn’t have if we had foreseen that the semi-holy ground that published correspondence once occupied would one day be overtaken by “The Selected E-mails of [Public Figure],” or—God forbid—“The Complete Tweets of @reallyfamousdude.”

Virtually every novelist of note for the last two centuries and more, to say nothing of thinkers and artists, was also a practiced—sometimes prolific and brilliant—letter-writer, and the bibliography of those figures often includes a volume or more of their written exchanges. Even the notoriously freaky and misanthropic H. P. Lovecraft, who found no use for “ordinary people” (which he confessed, somewhat ironically, in a personal letter to a correspondent who was very likely an ordinary person), still managed to write tens of thousands of letters, which take up five volumes in printed form. The writing of fiction has been, in general, coterminous with the writing of letters, and one may wonder what the future of the novel might be once it is unmoored from the regular discipline of writing and responding to hand-written letters. But more than the aesthetic value of such letters, which, no matter how atrocious the handwriting, is indisputably superior in every respect to email, published correspondence requires a patient community of often secret correspondents, who take the long risk of understanding and of being understood.

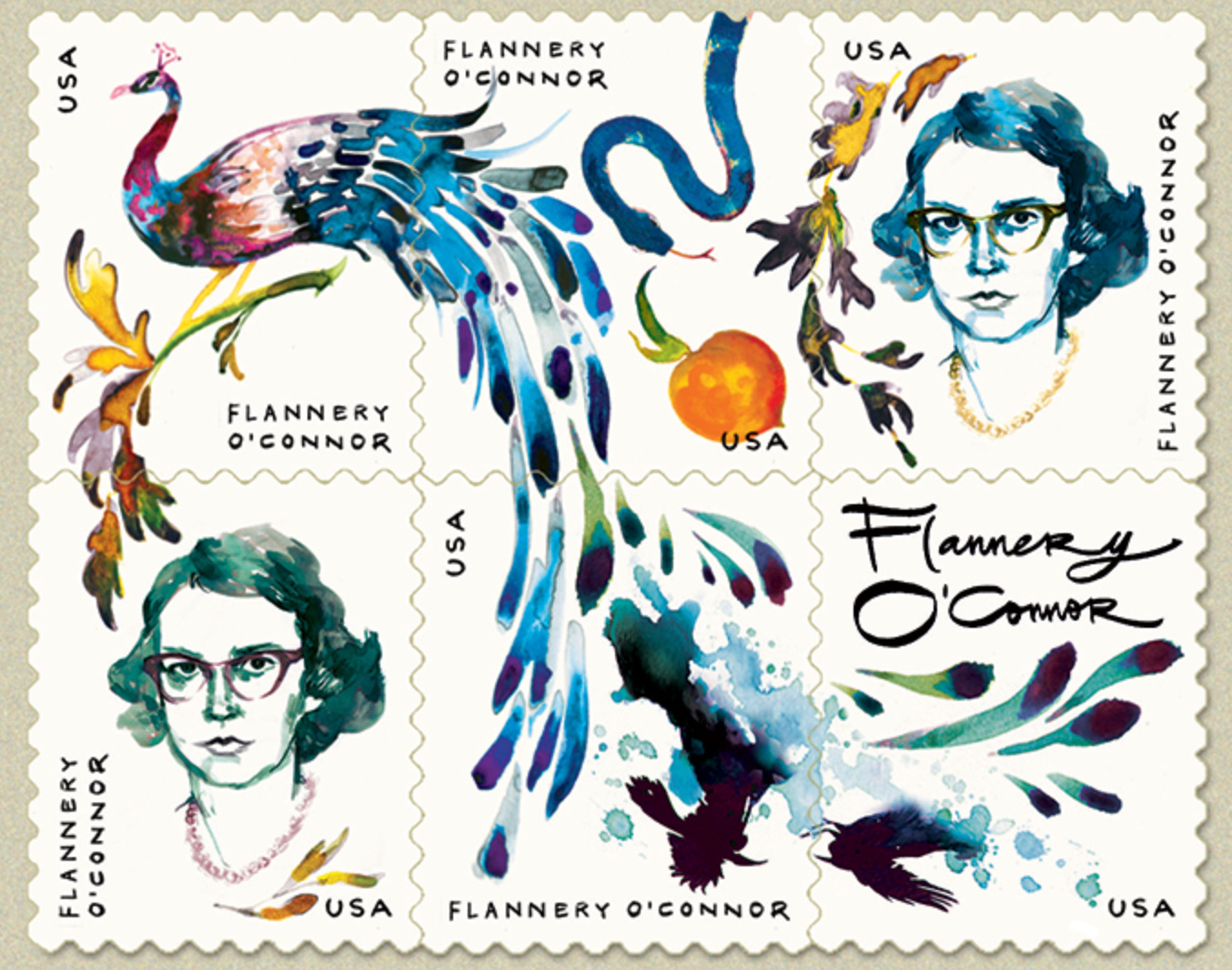

Flannery O’Connor was not only a great American short story writer and novelist, she was a letter writer of the first order. It is entirely apposite that the Postal Service honored her with a 93-cent stamp in 2015 (which is roughly the cost of mailing in a short story submission to The Sewanee Review). The collection of letters published as The Habit of Being in 1979 contains a sustained conversation with Betty Hester in almost three hundred letters, who until 2007 was known simply as “A.” “A.’s” letters are as revealing of their author as O’Connor’s responses are of herself. There will never be another Flannery O’Connor, nor will there ever be another Betty Hester. Personality, like a written letter, is unrepeatable. Digital communication, at least in its form, is not; and one has to wonder what effect of the form of contemporary communication might turn out to have upon the irreducibly singular character of human personhood.

Most people, I suspect, would say “not much.” I can’t claim to have any learned prognoses on this matter; but from the fact that we correspond with one another more frequently and efficiently now than ever before, it does not follow that we are any better at it, nor are we any better because of it. We are all too aware of how social isolation and loneliness increase along with our increased visibility on social media, and of the ease with which a personality can be manufactured and manipulated for maximum agreeableness. It is worth asking whether this may have anything to do with the form in which we conduct our electronic correspondence: digital, sans serif, monotonous, fixed-width, dull. The advantages of a handwritten letter over an email are practically self-evident, if little realized in practice: the former is a particular, singular, incarnated, and unrepeatable instantiation of a personality, all of the features of which have a mysterious capacity to communicate that personality, none of which features are characteristic of even the most emoji-adorned, inspiring-quote-signatured email.

I belong to the generation that learned to write in cursive and left college before email became the ubiquitous, default medium of correspondence that it has become. It appeared roughly in my junior year, in a primitive format that was to current email what the dot-matrix is to the laser printer: slower and less elegant, but still basically the same thing. It was greeted with something like a collective shrug, and I doubt anyone seriously believed then that it would transform the nature of interpersonal communication the way that it has. For several years after email’s appearance, many of us continued to keep in touch by way of hand-written letters, but eventually stopped, and yielded to the efficiency and convenience of electronic mail. But the letters remain, somewhere, a record of childhood, adolescence, early adulthood, and who knows what else, in some dusty box in the basement, where they wait indefinitely to be rediscovered, hopefully before some moment of late senility, or by my children when they reach the age when they want to get back at me for something.

By contrast, ten years ago I left a job with an eponymous email address that is now long defunct. A decade of emails, some important to me but most utterly mundane and forgettable, has vanished. In the best scenario, they have been merely spirited away into the ghostly limbo of cyberspace. But for some reason that I cannot entirely place, I was never able to summon the desire to retrieve that volume of correspondence, if it still exists, not least because I don’t know what I would do with it if I could. For them to become useful to me, they would have to become flesh again, mobile, freed of their servitude to electricity, where they could be read again in the dim twilight of remembrance or under the flash-lit covers of youthful discovery.

I have been trying, and mostly failing, to write more hand-written notes these days. I recently sent an unsolicited one to a friend whom I ran into at a retirement party for a mutual friend, and he had the great kindness to respond to my note—via Facebook message. While I was grateful for the somewhat asymmetrical semi-reciprocation, I couldn’t help feeling that either my friend had missed the point, or that somewhere along the way, our communication had misfired. Still, it was at least a response; so far, it is the only one I received to my modest fusillade of notes and cards to friends and, sometimes, strangers. I quickly learned that cultivating a hand-written correspondence is a lot harder than it seems.

Like many people, I have often moaned the “No Mail Blues,” if with far less musicality than Lightnin’ Hopkins and Memphis Slim. But at least they sang about it; it is telling that no one bothers to sing about getting either no email or too much. Perhaps an empty (real) mailbox is worth singing the blues about because we expect something from our mailboxes. Or at least I do, but it is possible that I expect too much, and only set myself up for daily disappointment. In spite of the fact that my daily mail is mostly chaff and little wheat, I still regard the mailbox as a site of daily wizardry and the delivery of the mail a species of ancient magic.

I don’t think I am a sentimentalist, but I find it impossible not to be inspired the quotation inscribed in stone above the James A. Farley Post Office in Midtown Manhattan:

NEITHER SNOW NOR RAIN NOR HEAT NOR GLOOM OF NIGHT STAYS THESE COURIERS FROM THE SWIFT COMPLETION OF THEIR APPOINTED ROUNDS.

It ultimately derives, in paraphrasis, from Herodotus, whose description of the Persian couriers in the eighth book of the Histories likened them to the Greek torch-runners in the festivals of Hephaestus. The analogy is apt.

The passage may be more believable, if less rousing, than the one a little further to the south that adorns the pedestal of the Statue of Liberty:

Give me your tired, your poor,

Your huddled masses yearning to breathe free,

The wretched refuse of your teeming shore.

Send these, the homeless, tempest-tost to me,

I lift my lamp beside the golden door!

A noble sentiment and a lofty ideal, but an aspiration about which the nation for whom it supposedly speaks has lately, perhaps never, been more than half-hearted. At least the Postal Service has been consistent in its effort to make good on its promise. The motto at JAF Station in New York might be a far less ambitious and stirring bit of civic verse than the lines under the Statue of Liberty; it might betray a steely devotion to a public service that is not readily visible on the drawn face of the average postal worker in your local post office, or on those of the hound-weary men and women in unattractive shorts and ghastly knee-high socks who make their daily rounds in fair weather. But it is perhaps nobler because it is a promise that is executed daily, with no fanfare, more akin to a long-practiced vow of marriage than the passionate exuberance of ruddy youth.

I know it is fashionable to make fun of the post office for its bureaucratism, its outdated business model, its lack of efficiency, for giving us the phrase “going postal” and so on, and Lord knows I do not particularly relish a chance to visit to my local branch. There once was a time when post offices were built like Greek temples or Italianate villas, when the grandeur of those structures was at least an attempt to do architectural justice to an intrinsically herculean occupation. My local, by contrast, is a seething hulk of poured concrete and crushed stone that resembles nothing so much as a dirty sidewalk turned on its side. But it is appropriate to the way we now collectively esteem the mail carrier, whom (The Simpsons notwithstanding) we no longer care enough about to make the object of satire.

Anyone with at least a modicum of knowledge about human beings and our capacity to disappoint and forget one another cannot fail to see the ability to deliver, in a handful of days, a hand-written communiqué of a unique personality across a country as vast and varied as the continental United States for sixty-three cents as anything less than an effing miracle. (The fact that jets have largely replaced thoroughbreds does nothing to diminish this fact.) To me, it is a miracle far more astonishing than the ability to send a bunch of ones and zeros anywhere electronically in a nanosecond, an achievement which is remarkable in its own way, but hardly inspiring, and certainly nothing worth singing the blues about. Like vinyl records and film negatives, snail mail is a species of analog slow art that simply staggers the imagination.

Yet, it is regrettable, maybe even damnable, that by inaction we have disparaged the high work of the heirs of Herodotus’ Persian torch-bearers by saddling them with the delivery of little more Pottery Barn catalogs (in all of their age-specific variants), Preferred Status™ Credit Card invitations, and weekly coupon inserts that are not actually inserted into anything. Once, mail carriers delivered portents; now they leave three copies of the American Girl catalog. But we have brought this on ourselves. Writing more personal letters will not save the Postal Service and its workers, although there is an outside chance that it might save us. The least we could do for our mail carriers, and for each other, is to give them something to deliver that is worth braving snow, rain, heat, and gloom of night for.

P.S. A black cat just ran under my window. True story.

Or, to cite another example: the “save” icon on your computer’s word processor is a reference to a 3.5-inch “floppy” disk that hasn’t been in use for a quarter-century. It’s a good example of the way language often becomes orphaned from its primary or originary sense of reference. One can see this in the rapidly-changing language of computer technology: what we called 3.5-inch floppy disks were stiff and unbending, not floppy at all—but the larger 5.25-inch disks they replaced were. We ditched the older technology, but hung on to the language.

Wow, Pete! You've said a mouthful here (truly), and I agree with all of it. A couple of comments: while I use email for lots of things, I've still retained, over the years, the idea that I can (yes, by God!) employ the technology to write "personal letters"! And I try to, complete with introductory remark (e.g, "Hi, [insert name here"] and a conclusion (or "sign off"), usually "Best." It's a little thing, but it still means a lot to me, though of course I can't speak for my "correspondents." Secondly, my advancing age has robbed me of the ability to write a pen-and-ink letter--in other words, my handwriting has become illegible (a failing I blame on all those years of writing marginal comments on papers submitted by students who never had the advantage of being taught by several old lady English teachers as I was "back in the day." Finally, I'm old enough that I've got a large number of file folders in basement cabinets jam-packed with my, um, "correspondence," BUT I've not really added to it for several years now. Guess I can check my computer file, right?