Vicksburg, Mississippi, used to be a riverfront town, but it’s not anymore. In 1876, the Mississippi that once flowed right past the historic center of Vicksburg decided to change course. And that left Vicksburg basically, not quite stranded, but certainly not riverfront property anymore. The once-grand steamboat port, one of the most exquisite, beautiful, dramatic stops for boat traffic along the Mississippi River wasn’t a stop anymore.

And after 1876, from the 1880s onwards, the railroads took over from steamboats. Transportation, and certainly freight, was carried more by railroads now than by steamboats. And Vicksburg, well, it kind of fell from grace. If not grace, necessarily, let’s say it fell from the Top Five.

When Vicksburg was established in the early 19th century, it was built along the Mississippi River. And of course, white Europeans who had been fairly new to Mississippi at this point—they had been there for a hundred and something, a hundred and thirty, forty years, probably not long enough to get the sense of the fact that the Mississippi River is not a stable entity. It is constantly moving. It is capricious. It does what it likes, and it doesn’t like to stay in one place. So at the time of its founding, Vicksburg fronted the Mississippi River, particularly a bend of the Mississippi River that, as the river comes south, it took a sharp turn north and then made a 180 degree bend southwards.

Along that southward stretch was the city of Vicksburg. That’s where it started.

A Riverfront Town No More

Well, in 1876, maybe the Mississippi got tired of making that sort of exhausting and unnecessary turn north and then turn south. And so it just decided to cut straight across that little tongue of land and head south, leaving Vicksburg no longer a riverfront town.

This wasn’t exactly great news for Vicksburg. The heart of Vicksburg was not right on the Mississippi River. And when railroads replaced steamboats as long haul freight carriers, Vicksburg was not quite as in demand as it used to be. Up to the end of the First World War, there was little river traffic in front of Vicksburg.

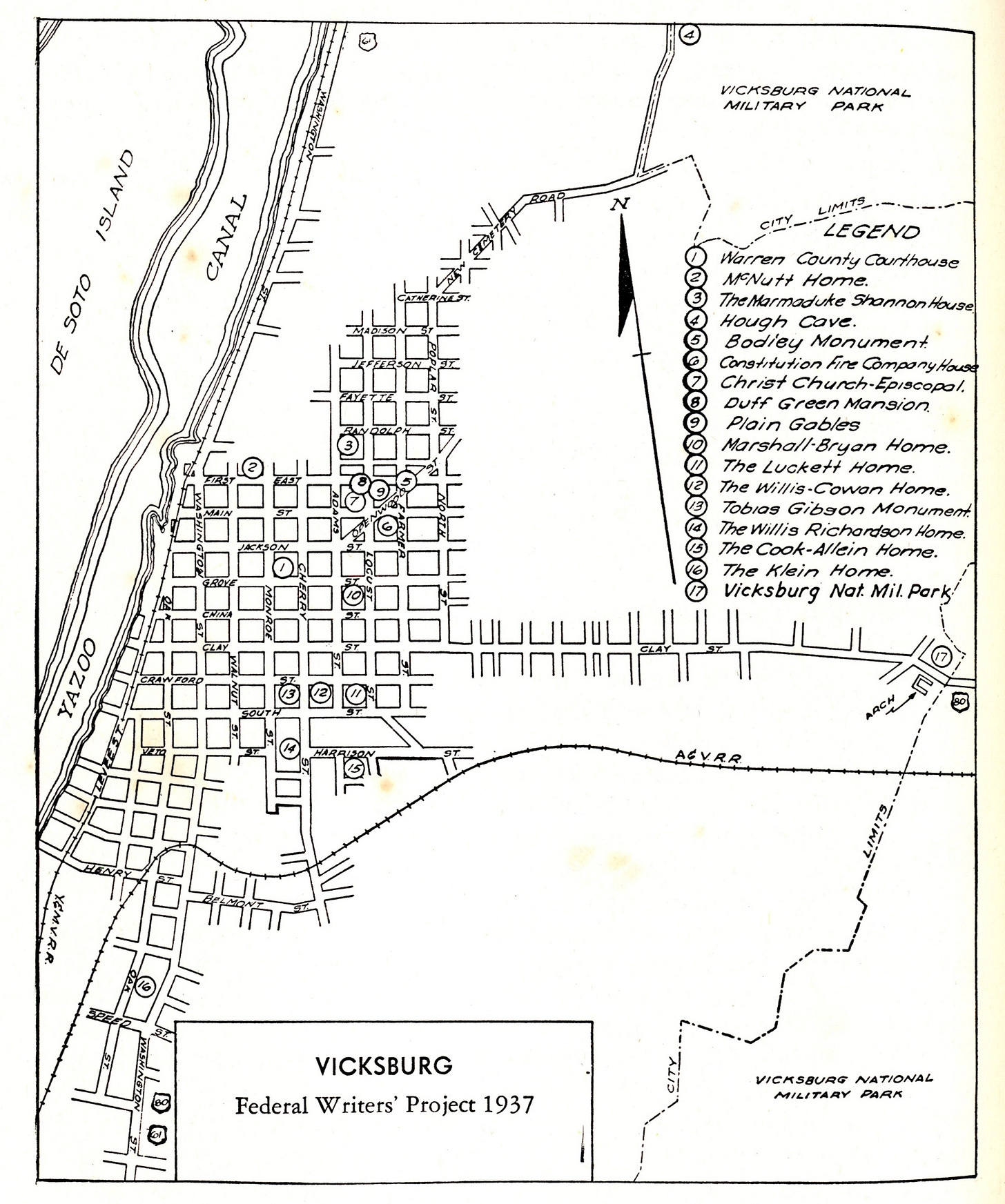

But it started to come back after the First World War, thanks to government subsidies towards a barge line on the Mississippi. In 1879, Congress created the Mississippi River Commission. So if you go to the heart of Vicksburg today, and you stand on these incredible loess bluffs, these silt deposits, essentially, they’re like sand dunes, but made out of clay. The high bluffs above the Mississippi River that made Vicksburg such an important strategic location, militarily speaking. You look across, you’re not looking across the Mississippi River. You’re looking at a canal that connects the Yazoo River to the Mississippi.

And this is where the Delta begins, or ends, depending on which direction you’re flowing. Vicksburg was established at the junction of the Yazoo River and the Mississippi River. In order to make Vicksburg a riverfront town once more, a canal was created connecting the Yazoo River to the Mississippi, running right in front of the heart of Vicksburg.

Every River Has a Story

The first time I really got a sense of the Mississippi was from the city park in Vicksburg, an overlook looking across the river to Louisiana, down river, south towards Davis Bend and ultimately New Orleans.

If you went north a little bit from that overlook, into the heart of Vicksburg, you would see something slightly different. And this is where the story gets weird and interesting because the story of Vicksburg is bound up with the story of the Mississippi River.

And you might not think that a river has a story, but if any river in the world has a story, it’s the Mississippi.

Where Would You Like Me to Put this River, Sir?

So after the Mississippi decided to change course, the story goes that a young boy had this idea. This was a year after the massacre in Vicksburg that claimed about 30 or more Black lives.

Why don’t we bring the Yazoo River down in front of Vicksburg? And according to the WPA Guide, the idea was “found practical.” “And so under government engineering the Yazoo’s mouth was closed and its waters were diverted through a canal into the old Mississippi River bed on December 22nd, 1902.”

Vicksburg again had a river coursing along the base of its bluffs. “Thus Vicksburg achieved the distinction of being moved from a river to a canal by an act of Congress.”

Of course, political boundaries don’t often keep up with the Mississippi River. If you look across the Yazoo Canal from Vicksburg, which used to be the Mississippi River, you’re actually looking at Louisiana. And then beyond that is Mississippi again.

But anyway. We’re starting in Vicksburg to go north through the Delta, not stand on the banks of the Mississippi or the Yazoo or any other body of water and stare across it indefinitely.

God Said, “Out on Highway 61”

Now if you head north from Vicksburg, you’ll be on Highway 61. We’ve talked about this highway before. It’s famous. Bob Dylan sang about it. It’s the spinal cord of American music. It hugs the edge of the Delta, the walnut hills to the east, and the flat alluvial plain of the Mississippi Delta to the west. And it is marked by lakes, oxbow lakes, rivers, creeks, bayous. It’s not quite a swamp. It’s a step or two above that. But it is a saturated landscape. And it’s saturated with more than just bodies of water. It’s saturated with stories. One of those stories is about Mound Bayou. We’ll get there in due course.

But in the meantime...

We head north on Highway 61 through Warren County into Issaquena County. Now you could take Highway 465, which will run right along the Mississippi River. And again, it’s a sort of ghostly route that it takes because it clearly hugged the boundary of the river at one point. But now the river is not there anymore.

It touches along Oxbow Lakes to the left of it, or rather to the west. But the shadows of the Mississippi are written onto the landscape all across the Delta, and even across the entire length of the Mississippi River.

Harold Fisk and the The Mississippi River Commission

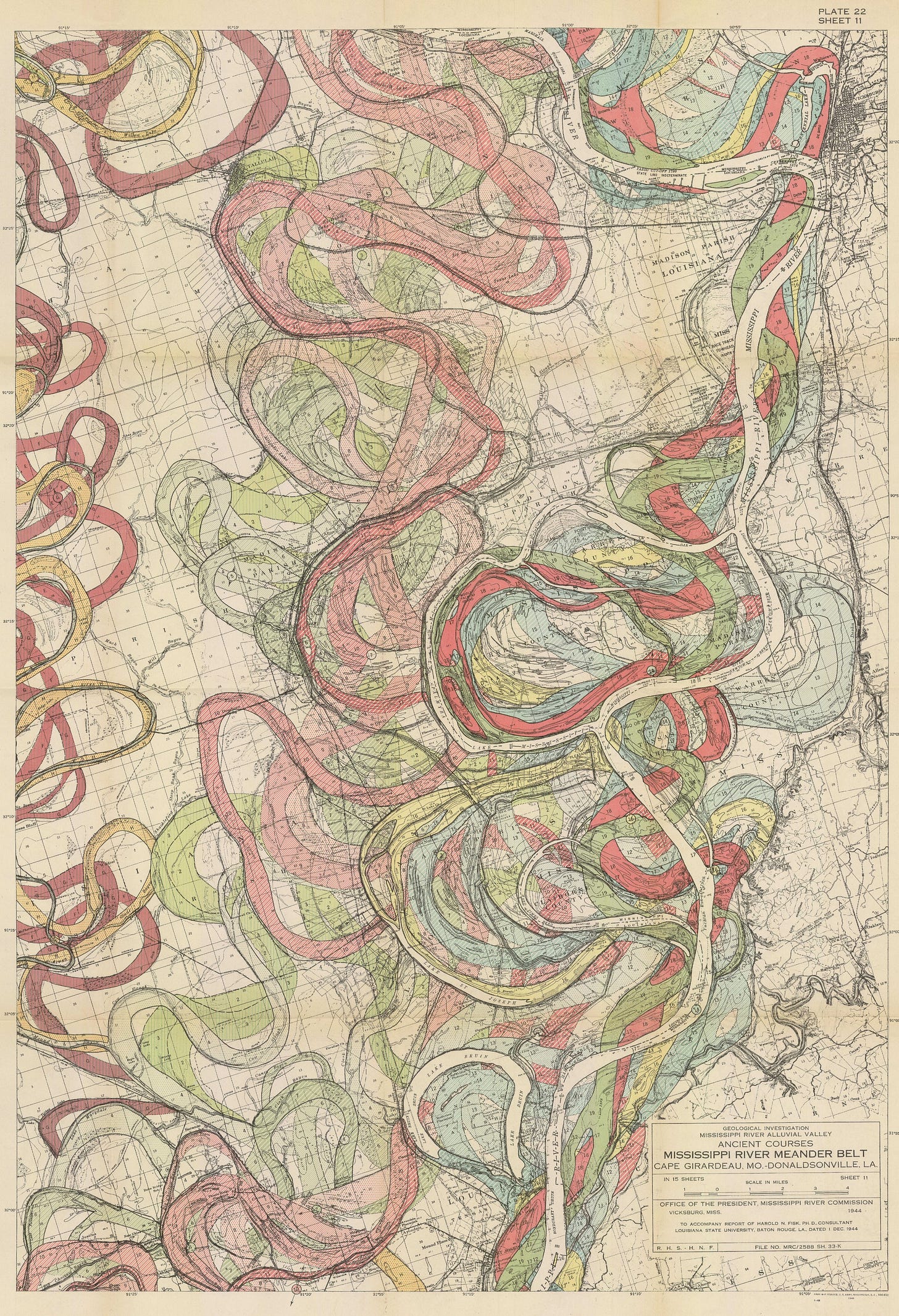

So in 1944, the Army Corps of Engineers had these maps made by Harold Fisk, who was a geographer for the Mississippi River Commission. He was a Ph. D. He’s listed as a consultant on these maps from Louisiana State University, LSU, in Baton Rouge.

The Mississippi River Commission was established in 1879, three years after the Mississippi decided it didn’t want to go the way it went before. The Commission was organized in order to survey the river and improve its channels and so forth, prevent floods and all of the rest. In 1944, the Mississippi River Commission based in Vicksburg commissioned these maps to be drawn of the entire length of the Mississippi River—well, most of it—that would document the way the river has changed course over hundreds and hundreds of years. So they hired this guy, Harold Fisk, to draw these maps, and they’re incredible. They show you the main channel of the Mississippi River, and then in different, very kind of 1940s colors, almost pastel-y corals and sky blue and light orange and greens, they show the shadow-forms of the Mississippi’s previous routes. And they’re extraordinary maps. If you’ve seen redlining maps from the same era, the color scheme is very similar, but they’re doing something very different here.

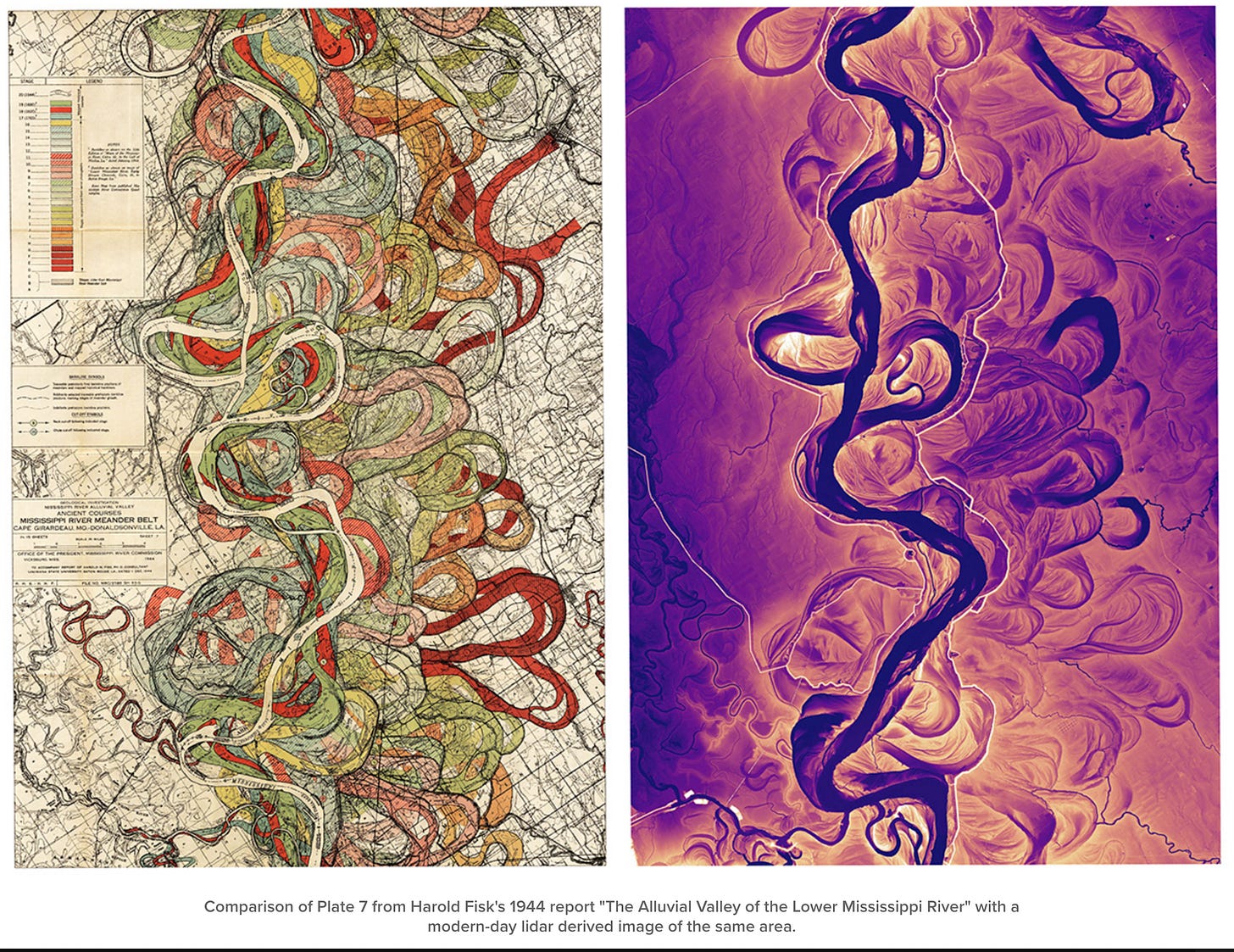

You’re looking at thousands of years of geological time compressed into a single image. The main river is blank, kind of white. But its previous pathways are in these beautiful hues. And they’re extraordinary to look at, just an amazing example of cartography. And if you’re a map nerd like I am, you can spend hours just looking and staring at these maps, just marveling at the beauty of them. Recently, they’ve been updated by a guy called Daniel Coe, he’s sort of like the 21st century version of Harold Fisk. He works for the Washington Geological Survey in Olympia, Washington. He’s a graphics editor. He took some LiDAR images of these same stretches of the Mississippi River—LiDAR is like a fancy type of photography using lasers and radar and all kinds of crazy stuff—and he has these images that basically update Fisk’s maps. In these incredible digital pallettes—they tend to be monochrome in one color or another—they show the sinuous waves in the landscape that the Mississippi River has created over millennia. They’re extraordinary.

He’s even done a sort of dynamic image where he takes Fisk’s map of a certain section of the Mississippi and you see it morph into his LiDAR high tech image of it:

So there are some things that you can’t see on foot. Some things you have to be at 30,000 feet in order to get the big picture of the landscape.

Oxbow Lakes & The Interstate of American Memory

You can see the ways in which the Mississippi River has indelibly marked the land in the United States, when the Mississippi has moved, when it’s changed its course and decided to bend in a different direction or at a different place. The old bends in the river have now been abandoned, and they’re all over the place along the Mississippi River. They’re called “oxbow lakes” because of their shape, and they’re all shaped in a sort of curve.

It’s an unusual geological feature. It’s also a really powerful metaphor for all of the kinds of things in American history that get abandoned by what I’ve sometimes called the interstate of American memory. In our pursuit of efficiency and speed, we have abandoned aspects of our history that, frankly, we would probably rather ignore altogether. But they’re like these oxbow lakes: they have become removed from the main course of American history and sometimes forgotten altogether.

So you can’t put these oxbow lakes back into the Mississippi River, but you can at least remember the way in which they were part of the river at one time. They shaped the landscape in the same way some of the episodes that we have already experienced, like for example, the massacre in Vicksburg in 1875. It’s indelibly marked the landscape of American history, but it’s like one of those oxbow lakes of history that is off to one side. You might stumble upon it, but it doesn’t connect, for most people, to the main story of American history.

See Harold Fisk’s meander maps of the lower Mississippi River valley.

Buy prints, if you want to.

Daniel Coe’s LiDAR images of the Mississippi and other river systems.

See Cathy Fussell’s quilt versions of some of Fisk’s maps.