I had never set foot in Knoxville, Tennessee until July 2022, when John Hayes and I stopped there on the first day of our ninth Southern tour. I’ve driven through it many times on the interstate, which isn’t really driving through a place as much as driving over it. What little I knew of Knoxville was limited to the peripheral view from I-40, and Neyland Stadium, an intimidatingly large and loud football field for the University of Tennessee. For many years Neyland Stadium was the graveyard of Georgia football fans’ championship dreams, and for the entire decade from 1989-1999, the Dawgs couldn’t win for losing against UT in Knoxville (or in Athens, for that matter). The venue seats over 100,000 mostly orange people who will make you never want to hear “Rocky Top” again as long as you live. It’s not quite the Appalachian Mordor it once was, but my first urge upon alighting in Knoxville was to lay eyes on this erstwhile source of terror if only to domesticate it.

Since my first fly-bys around Knoxville, I have had a little more to go on, thanks mostly to James Agee’s richly evocative depiction of the city in his brilliant 1957 novel, A Death in the Family. In the opening section, he lyrically riffs on the scene in the Fort Sanders neighborhood where he grew up:

People go by; things go by. A horse, drawing a buggy, breaking his hollow iron music on the asphalt; a loud auto; a quiet auto; people in pairs, not in a hurry, scuffling, switching their weights of aestival body, talking casually, the taste hovering over them of vanilla, strawberry, pasteboard and starched milk…1

Samuel Barber drew from this text for his 1947 piece for voice and orchestra, entitled, like the opening section of Agee’s novel, Knoxville: Summer, 1915.2 The neighborhood around the former Agee home is quite different now, naturally. The town has been through some major shifts in the 107 years since Agee’s Knoxville in the summer of 1915.3 There is still asphalt, though—lots more of it, and lots more loud autos, breaking even hollower “iron music.” I don’t know about downtown and in the neighborhoods, but on the prodigious interstates in and around the city, no one is “not in a hurry.”

The Agee home itself was torn down years ago. The novelist James McMurtry, an Agee fan, once tried to find it, too, but got stuck in traffic on Knoxville’s far less lyrical interstates and couldn’t find his way out.4

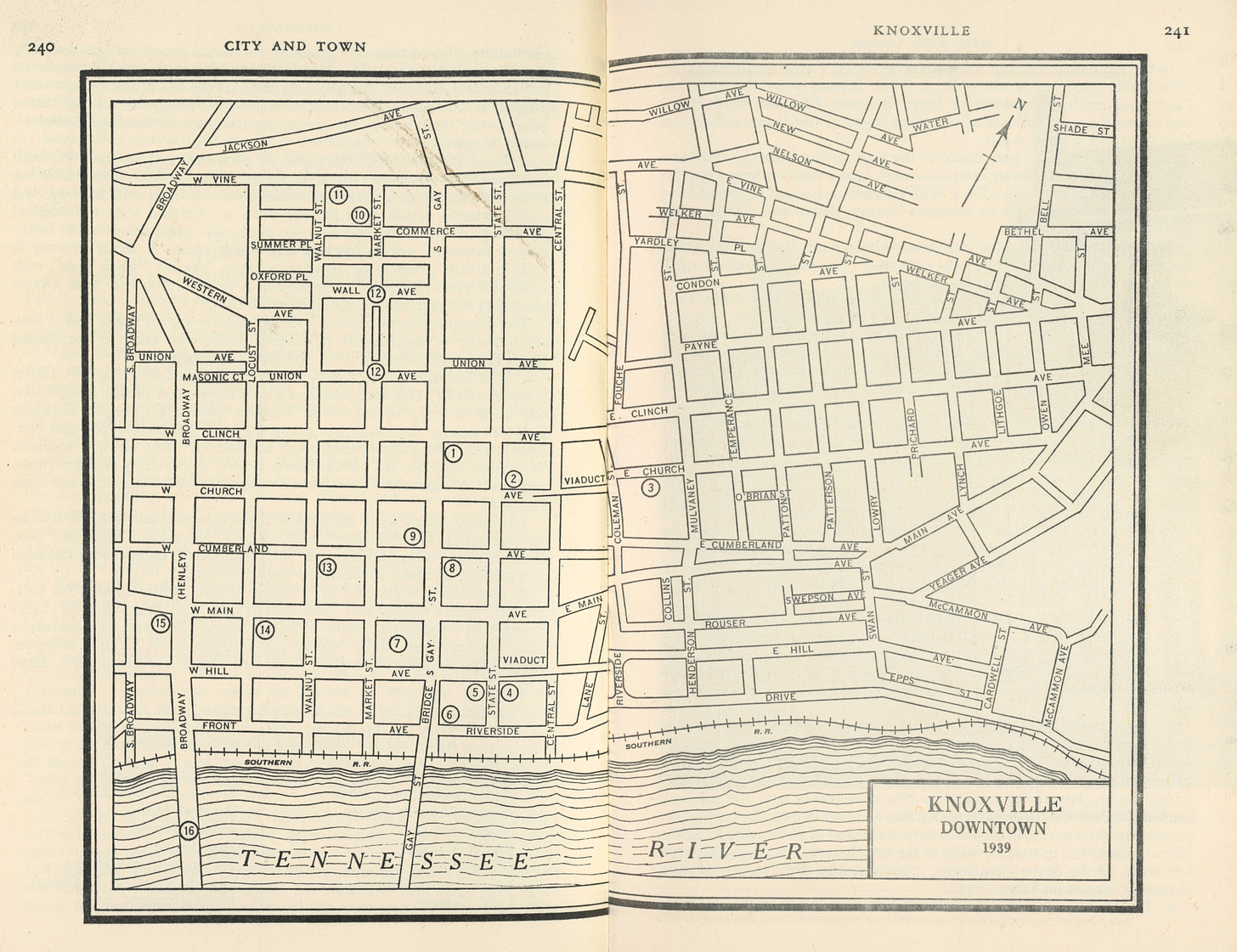

On our visit this past summer, Knoxville first appears a fragmented city, clearly severed into different pieces by the advent of Interstate 40 in the 1950s. It is difficult to find a middle to it all. One small section at the corner of Jackson and Central feels like a center: 19th century buildings have been re-purposed into restaurants, bars, clothing boutiques with a decidedly hipster feel. Ampersands abound. It seems close to a downtown but is not quite there.

The World’s Fair Park constructed in the 1980s doesn’t feel quite there, either:

Eventually we find the heart of old Knoxville rising up from the banks of the Tennessee River at its southern boundary. Where the Gay Street bridge crosses the river into downtown Knoxville, the Andrew Johnson Hotel marks the heart of the early country music broadcasting and recording industry; nearby the Blount Mansion, built in 1792, was the home of William Blount, Governor of the Southwest Territory, as it was then known. But more interesting to both me and John is the nearby plaque marking the fact that Hank Williams spent his last night alive in the Johnson Hotel.

Gay Street, the main drag in Knoxville, is emblematic of this fascinating city’s divided loyalties. In 1861, Knoxville was split between Unionists and secessionists. Eastern Tennessee, made up largely of small farms and few (but not no) slaveholders, was largely pro-Union. Knoxville was far from a Confederate stronghold, but pro-secessionist sentiment was higher here than it was in the surrounding hills, and to the east. This schizophrenia manifested itself in April, 1861, when competing rallies on Gay Street represented the tension at the heart of the city. At one end of Gay Street, pro-Confederacy elements demonstrated in support of secession; on the other end, Unionists listened to speeches passionately defending the Union. Samuel Bell Palmer, a young Knoxville resident, drew a pencil sketch of the scene:

Not long after the dueling rallies, Knoxville, unlike the rest of eastern Tennessee, ultimately cast its fortunes with secession. Palmer did, too—he joined the Confederate Army, but was captured during the Union occupation of Knoxville in 1863, and sent to Camp Douglas in Illinois, where he drew the above sketch from memory.

Larry McMurtry apparently didn’t see this side of Gay Street, either, stuck as he was on the overpass. Maybe he was as surprised as I was to find Knoxville such a twisted tangle of concrete.5 I’m familiar with the ways in which the interstate changed so dramatically the landscape of downtown Atlanta, and of the ways other cities like New York and New Orleans managed to avoid this fate. I wasn’t aware how much the interstate had impacted Knoxville, but I wasn’t especially surprised.

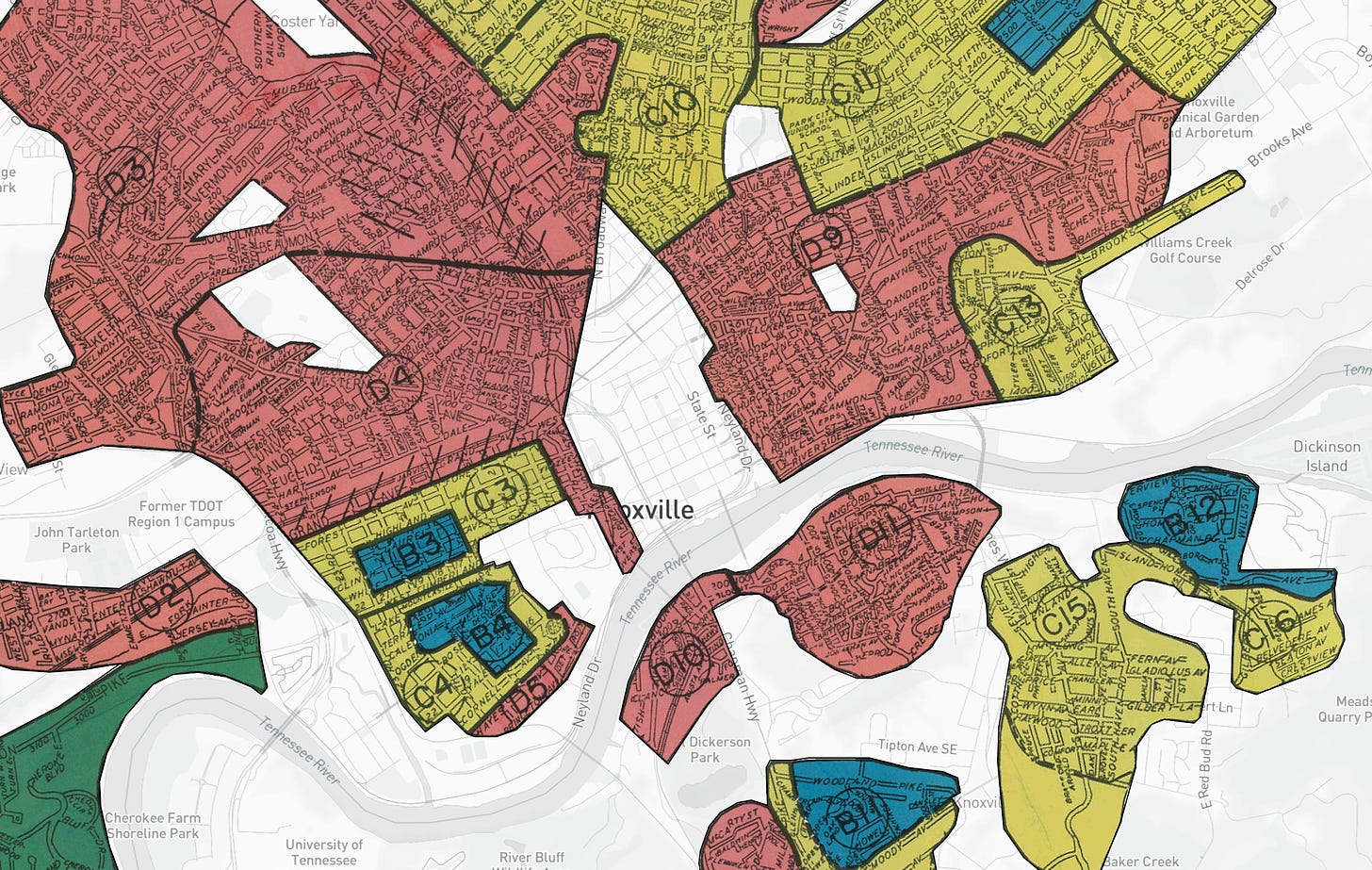

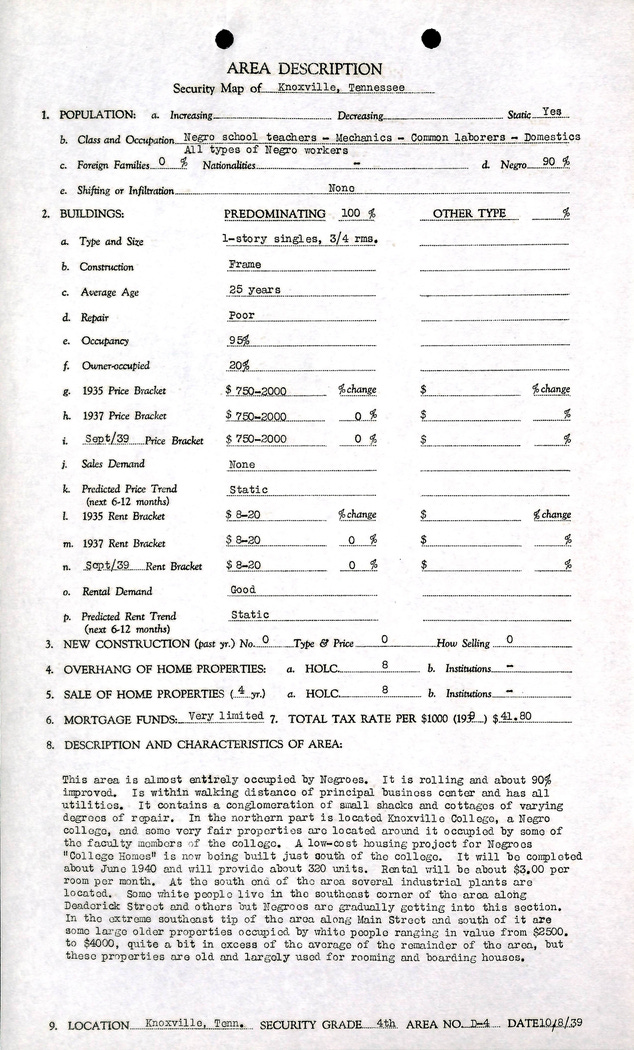

What happened to Knoxville is a familiar story. Just as in Atlanta, where interstate highways were mapped out to concretize racial segregation, sometimes systematically destroying Black neighborhoods, the major interchanges in Knoxville (I-275 and I-40, and I-40 and US 11) fall on plots of land once marked “Hazardous” according to a 1939 HOLC (Home Owners’ Loan Corporation) “redlining” map.

The HOLC map notes that the area marked D4 is “almost entirely occupied by Negroes. It is rolling and about 90% improved. Is within walking distance of principal business center and has all utilities. It contains a conglomeration of small shacks and cottages of varying degrees of repair…Some white people live in the southeast corner of the area along Deaderick Street and others but Negroes are gradually getting into this section.”6 Today, I-40 runs directly over this section of the city.

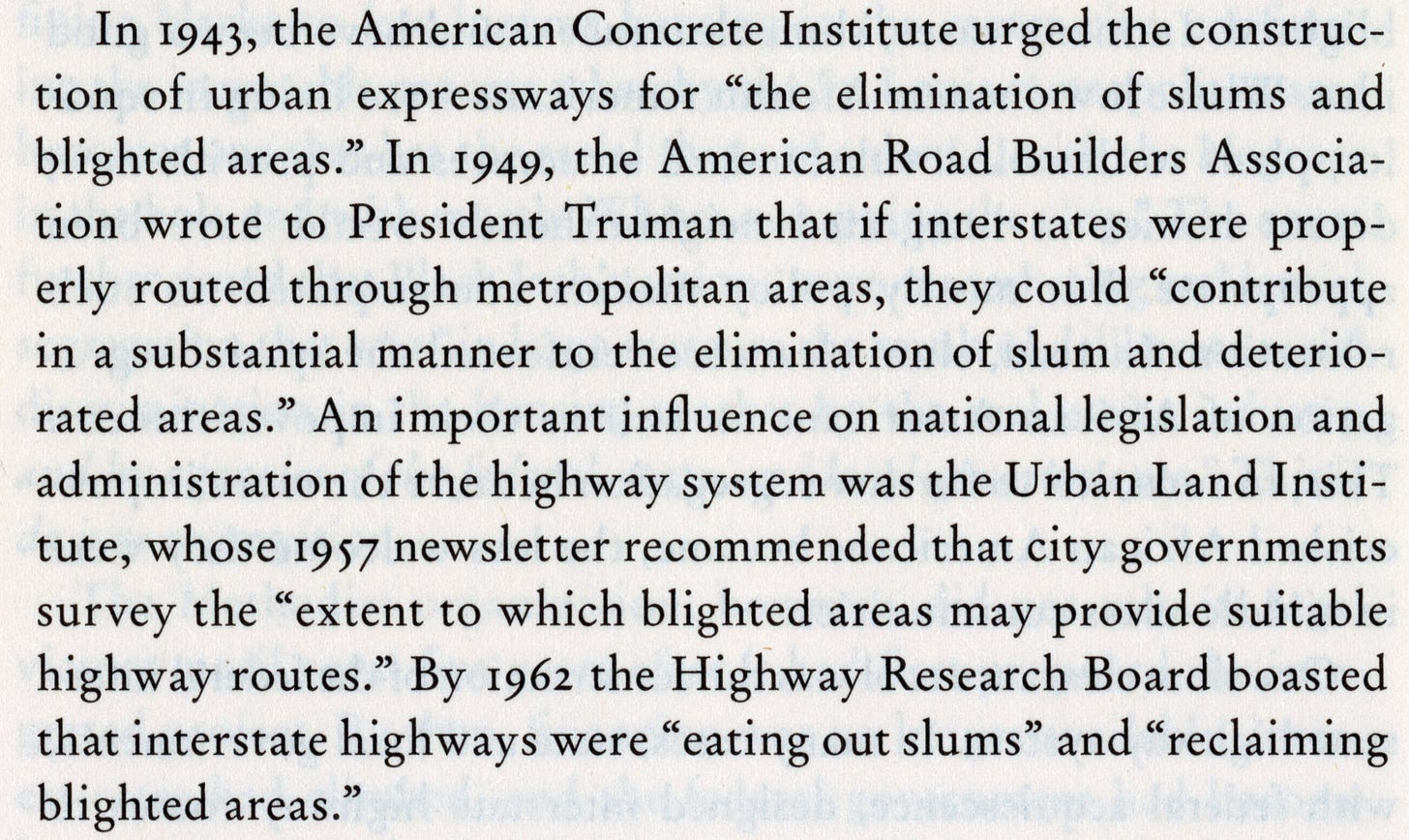

Redlined neighborhoods were explicitly denied funding from federal lending agencies, and often became the targets for city planners in thrall to the new interstate highway system as a tool for de facto segregation under the aegis of “slum clearance.” As Richard Rothstein notes, this is a story where “progress” meets outright racial apartheid:7

So let Larry McMurtry on I-40 in Knoxville serve as the metaphor of the day: a novelist seeking out the former home of another novelist cannot get there because of gridlock on the interstate highways that were supposed to make travel more efficient. A writer in search of his sources cannot find them because the design of the city has only begrudgingly and barely preserved the site at all, made access to it (on this day, at least) nearly impossible, and obscured the real reasons why the big roads he is stuck on were laid out this way. It could be that the only thing interstate highways have really made more efficient is ignorance of our American selves.

James Agee, A Death in the Family (New York: Penguin 2008), p. 6.

So how did Barber compose this piece in 1947, if the book wasn’t published until 1957? Excellent question. Agee had the “Knoxville: Summer, 1915” piece published as a prose poem in The Partisan Review in 1938. It was not originally part of the manuscript for A Death in the Family that Agee left incomplete at his sudden death from a heart attack in 1955. It was included by editor David McDowell in his reconstruction, published in 1957 by McDowell, Obolensky, Inc., a company established mainly for the publication of Agee’s book, which won the Pulitzer Prize in 1958. In 2008 Michael Lofaro released a “restoration” of Agee’s allegedly intended text. I commend Steve Earle’s introductory essay in the Penguin edition of A Death in the Family for his handling of the controversy over which is the “real” version Agee intended.

In the early 1980’s, local residents fought over whether the Fort Sanders neighborhood should be designated a National Historic District, and opposition was strong enough to prevent the City Council from imposing zoning restrictions on the neighborhood. If you can’t get there to see the neighborhood for yourself, read about how much the neighborhood has changed since Agee’s time in Charles S. Aiken, “The Transformation of James Agee's Knoxville,” Geographical Review 73.2 (April 1983), pp. 150-165.

Larry McMurtry, Roads: Driving America’s Great Highways (New York: Simon & Schuster, 2000), p. 174.

But maybe also differently: he seemed to like interstates more than I do, and in his interstate-centric travelogue, Roads, confessed to having little interest in following “what remains of these old, difficult roads” (p. 14).

Richard Rothstein, The Color of Law: A Forgotten History of How Our Government Segregated America (New York: Liveright, 2017), p. 128.

Absolutely awesome!!! Sending it out to many…..our good friends, John and Linda Morgan are both from Tennessee big Tennessee football fans. They will Looooove this…as will SOOO many👏👏👏👏👏🙏❤️❤️❤️❤️❤️❤️❤️Love and so proud of you,

Mom❤️